Abstract

Objective: Several studies have demonstrated increased postoperative mortality rates in patients on chronic hemodialysis compared with non-dialyzed patients. However, limited studies have examined factors that may contribute to postoperative mortality.

Methods: In this retrospective cohort study, data were collected from 9,140 dialysis and 45,725 non-dialysis patients undergoing surgery between 2007 to 2009 from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Registry Database. Patient demographics, comorbidities, and anesthesia duration were used to compare 30-day postoperative mortality differences in dialysis patients.

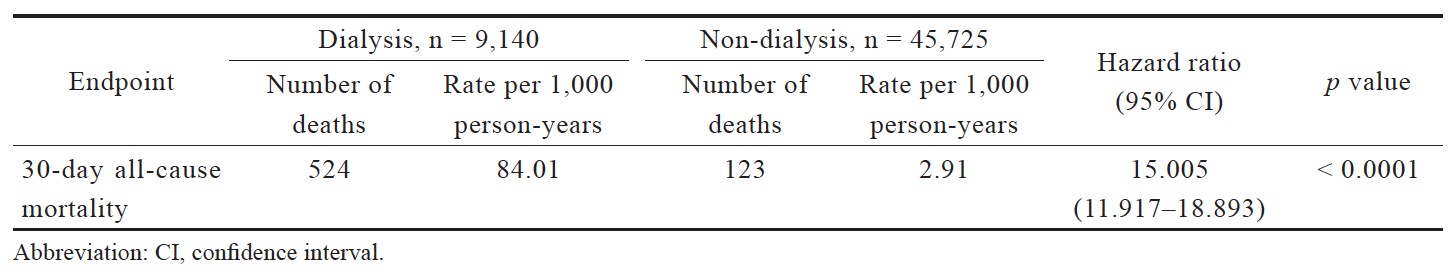

Results: Dialysis patients undergoing first-time surgery were significantly older, more likely male, and possessed more comorbidities. Overall, dialysis patients had significantly higher all-cause postoperative mortality (odds ratio, 15.005; 95% confidence interval, 11.917–18.893). Gender (hazard ratio [HR], 0.762), age (HR, 1.012), longer duration of inhalation general anesthesia (HR, 1.113), and comorbidities of hypertension (HR, 0.759), diabetes (HR, 1.339), congestive heart failure (HR, 1.232), coronary artery disease (HR, 1.326), cerebral vascular accident (HR, 1.312), intracranial hemorrhage (HR, 6.765), gastrointestinal bleeding (HR, 1.396), and liver cirrhosis (HR, 2.027), independently increased postoperative mortality risk in dialysis patients. Of the comorbidities, intracranial hemorrhage posed the greatest risk.

Conclusion: Patient demographics, anesthesia factors, and comorbidities help dialysis patients understand their postoperative mortality. These potential risk factors also inform anesthesiologists and surgeons weight perioperative conditions in dialysis patients before surgery.

Keywords

dialysis, end stage renal disease, surgical mortality, anesthesia

Introduction

End stage renal disease (ESRD), the last stage of chronic irreversible renal failure, is a significant worldwide problem most often managed by dialysis. In the past decade, incidence rates of ESRD have been increasing worldwide, especially in developing countries.1 ESRD is associated with a host of comorbidities that may require surgical intervention. With the rising ESRD rates and improvements in renal care, increasing numbers of surgeries are being performed on dialysis patients. However, studies show that dialysis patients have increased risk of postoperative complications and 30-day mortality compared to their non-dialysis counterparts, in both cardiac and noncardiac surgeries.2-4 It is also important to understand factors that influence postoperative mortality for dialysis patients. This understanding helps both the patients and clinicians to weight perioperative plans for dialysis patients to reduce potential adverse events. Mortality factors include medical comorbidities, notably of the heart, liver, and brain. It has been demonstrated that cardiovascular disease accounts for the greatest postoperative mortality rate among ESRD patients.5 Another important mortality factor is anesthesia delivery. Though several studies have compared postoperative mortality rates of general versus regional anesthesia, with varying results,6,7 limited studies have examined the impact of anesthesia method on dialyzed patients specifically.

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study to determine risk factors for postoperative mortality in dialysis patients from patients’ view. First, we compared postoperative mortality in dialysis and non-dialysis patients receiving their first-time surgeries. Amongst dialysis patients, we then examined the mortality impact from patient demographics, common comorbidities, and regional versus general anesthesia. The aim of our study is to aid dialysis patients and anesthesiologists in making informed decisions regarding surgery and identifying high-risk patients for their additional preoperative tests and postoperative care. For patients, a huge variety of different surgeries and their risks can be difficult to understand but their comorbidity status provides patients with a more familiar framework with which to assess their own operative risk. Our data on anesthesia risk provides an additional tool for anesthesiologists to better counsel for preoperative patients.

Methods

Data Source

Our study data was obtained from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Taiwan’s NHI, launched in 1995, is a compulsory single-payer national insurance program that enrolls over 99% of the country’s population. Within the NHIRD is the Registry for Catastrophic Illnesses, which registers patients with major illnesses, including ESRD. Inclusion in the registry requires diagnostic confirmation by two nephrologists, and the information is subject to random reviews by the NHI. In a previous study, Hsieh et al. had validated the accuracy of diagnostic codes in the NHIRD in identifying patients with renal dysfunction.8

Our dialysis cohort cases were retrieved from de-identified secondary data in the Registry for Catastrophic Illnesses. Registry data for dialyzed patients included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes, date of diagnosis, date of death, dates of dialysis and clinical visits, prescription details, and details of outpatient/inpatient claims. Approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Cheng Kung University Hospital (IRB No: --/A-ER-103-350-T) and a waiver of patient consent were obtained prior to data collection.

Study Cohort

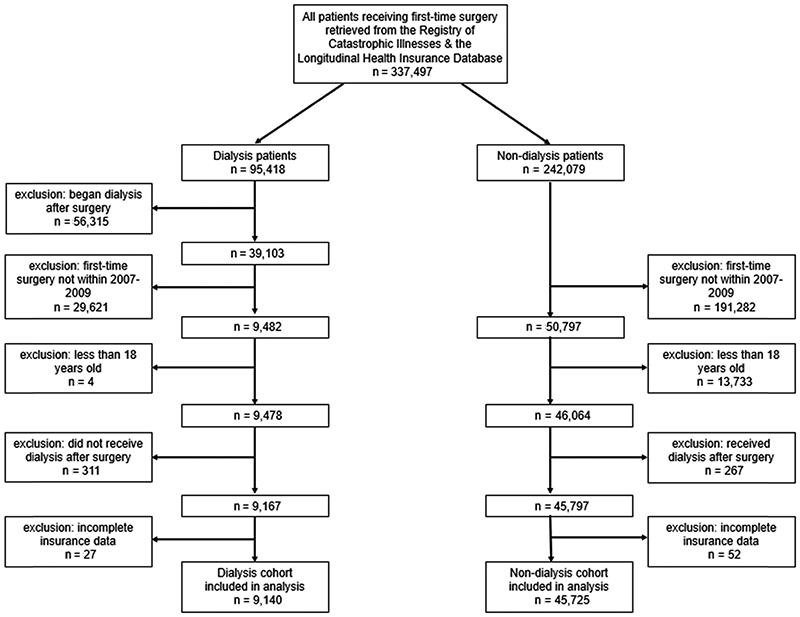

Patients who underwent surgery between 2007–2009 were identified using ICD-9 procedure terminology codes. Incident long term dialysis patients were identified from the Registry for Catastrophic Illnesses, defined as patients with Catastrophic Illnesses registration cards for ESRD who had received more than 90 days of hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, were not long-term dialysis patients, or underwent first-time surgery prior to starting dialysis. Non-dialysis adult patients were identified from the NHIRD (Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010 [LHID 2010]). More detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1.

Download full-size image

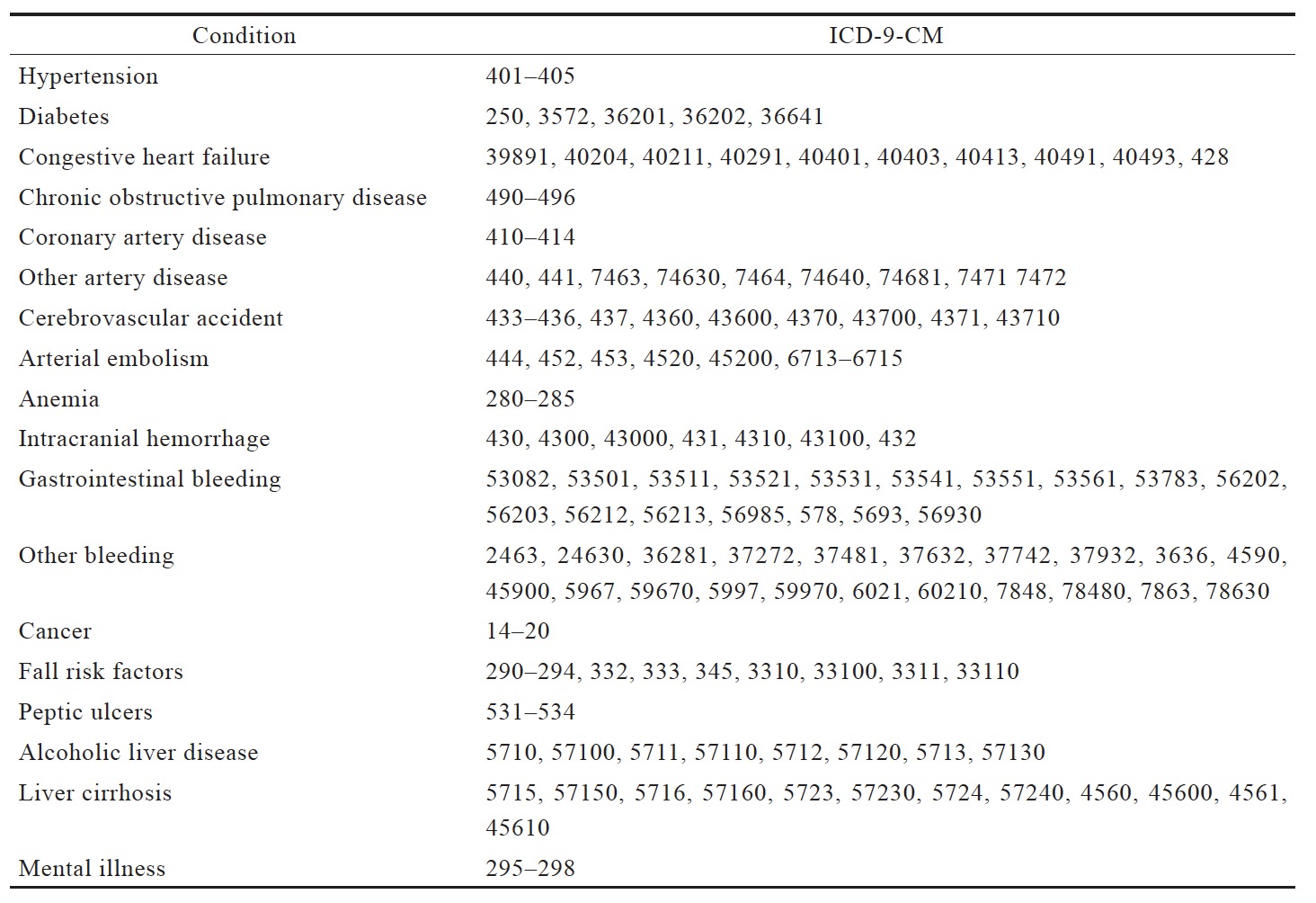

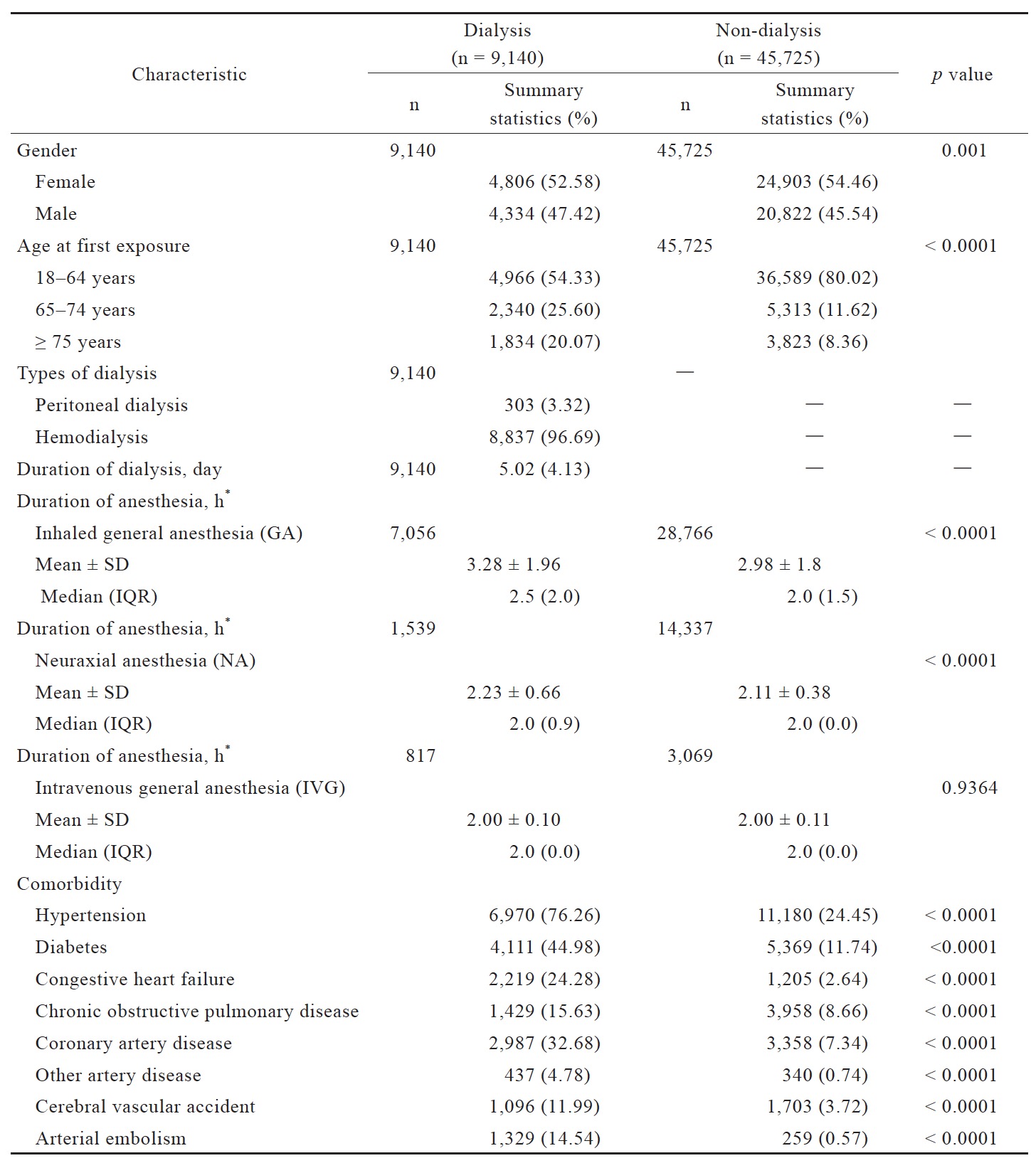

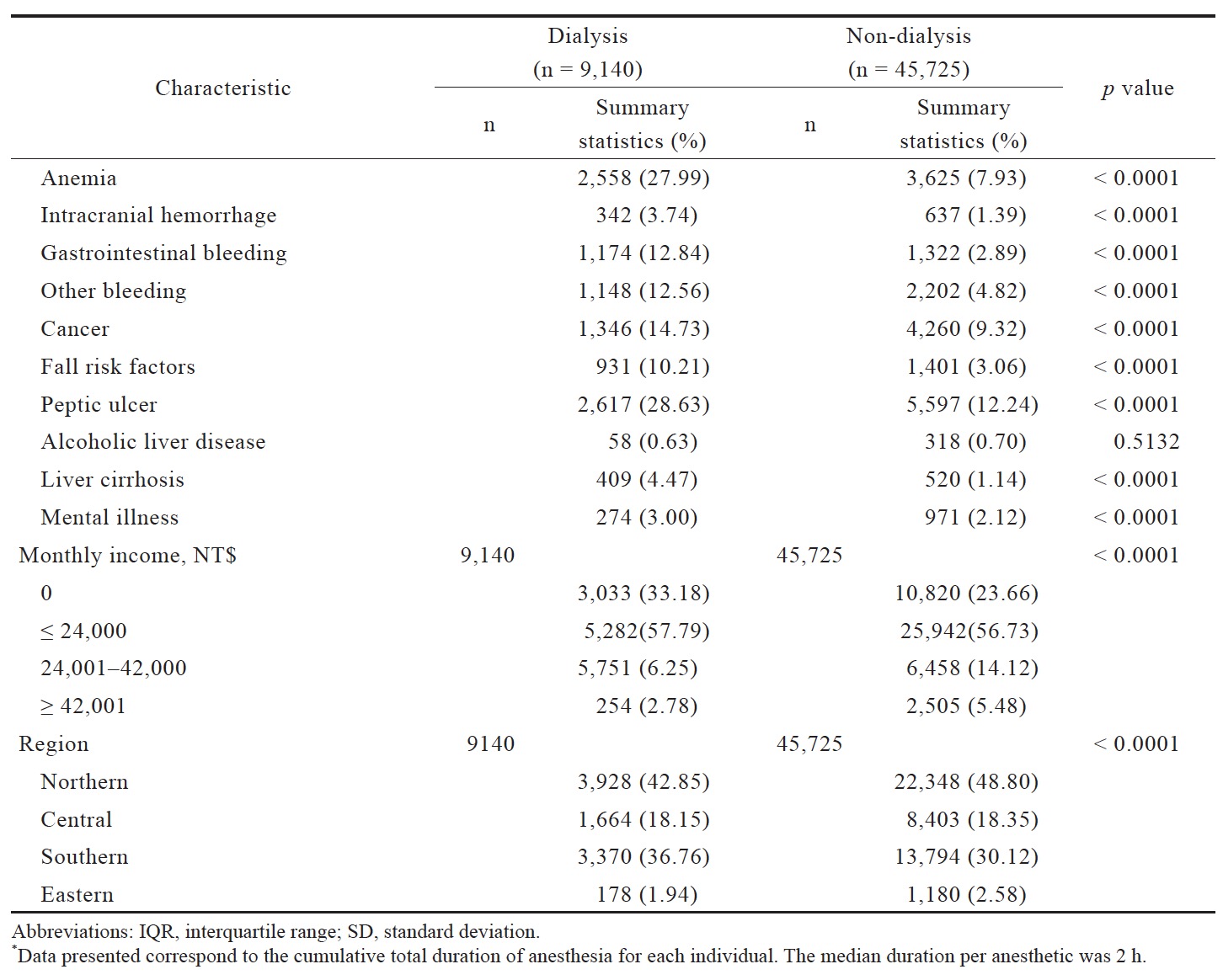

Existing comorbidities were recorded from all inpatient and outpatient ICD-9 codes, as listed in Table 1. Comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease (CAD), other artery disease, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), arterial embolism, anemia, intracranial hemorrhage, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, other bleeding, cancer, fall risk factors, peptic ulcers, alcoholic liver disease, liver cirrhosis, and mental illness.

Download full-size image

Using anesthesia treatment codes, we recorded the type of anesthesia administered during surgery. General anesthesia was categorized into inhaled and intravenous delivery (code 96017c or 96020c), and regional anesthesia included neuraxial techniques (single-shot spinal, continuous spinal, or continuous epidural) with or without a continuous peripheral nerve block (code 96008c, 96005c or 96013c). Patients, who failed neuraxial block, were then inducted with general anesthesia included in the general anesthesia groups for analysis.

Outcomes

We reviewed the Registry for Catastrophic Illnesses and LHID 2010 for information on 30-day postoperative all-cause mortality, defined as any of the following occurring within 30 days of the operation: discharge status coded “death”, discharge under terminal status, and date of death on the Catastrophic Illness registry, or withdrawal from the NHI. Multivariable analyses were performed to control for covariates in the patient’s baseline characteristics, including: age at surgery, dialysis duration, anesthesia duration, comorbidities, income, and geographic region.

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as proportions or means ±

standard deviation as appropriate. All statistical tests were 2-sided. Categorical variables were compared using a chi-squared test, and continuous variables were compared using Student’st test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

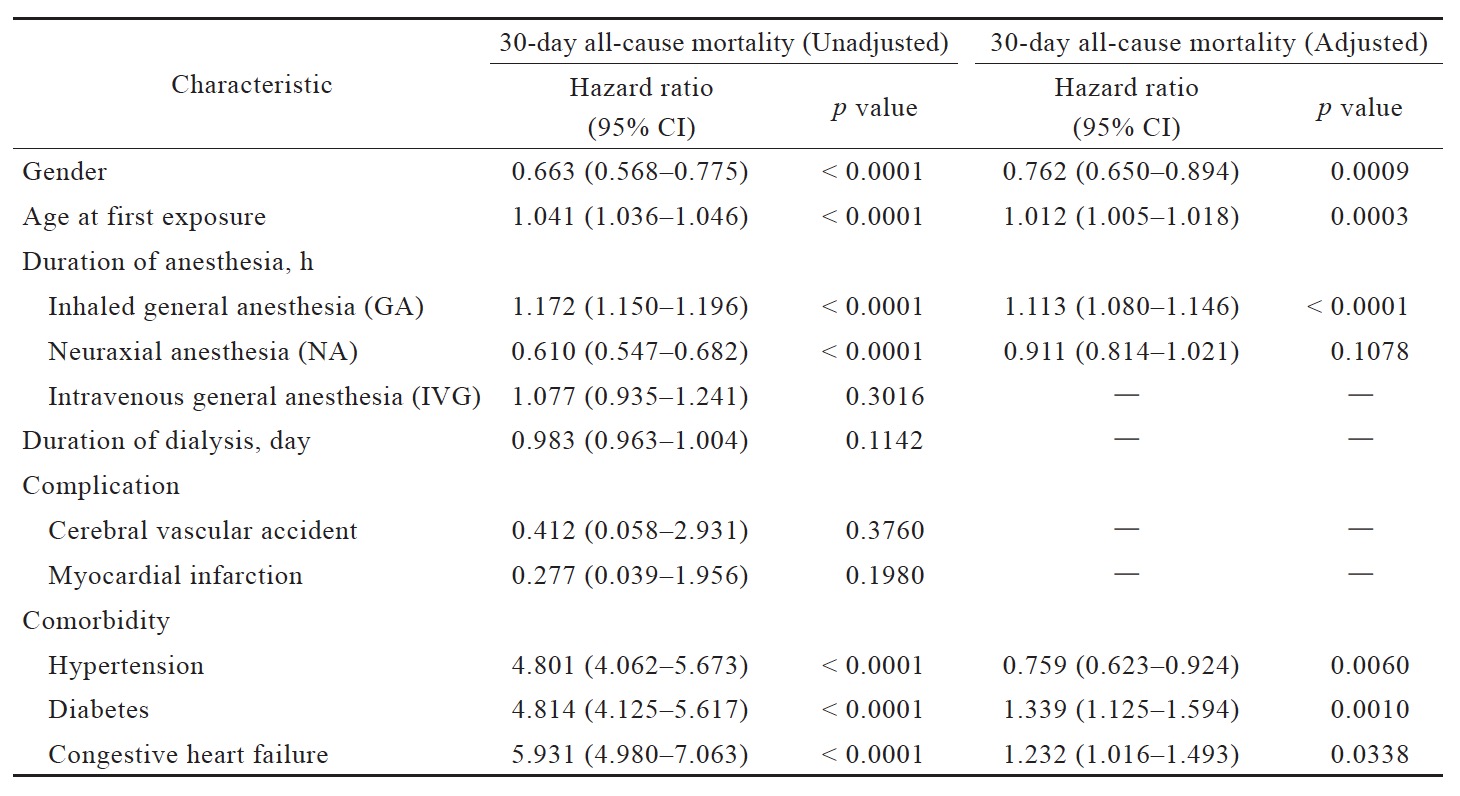

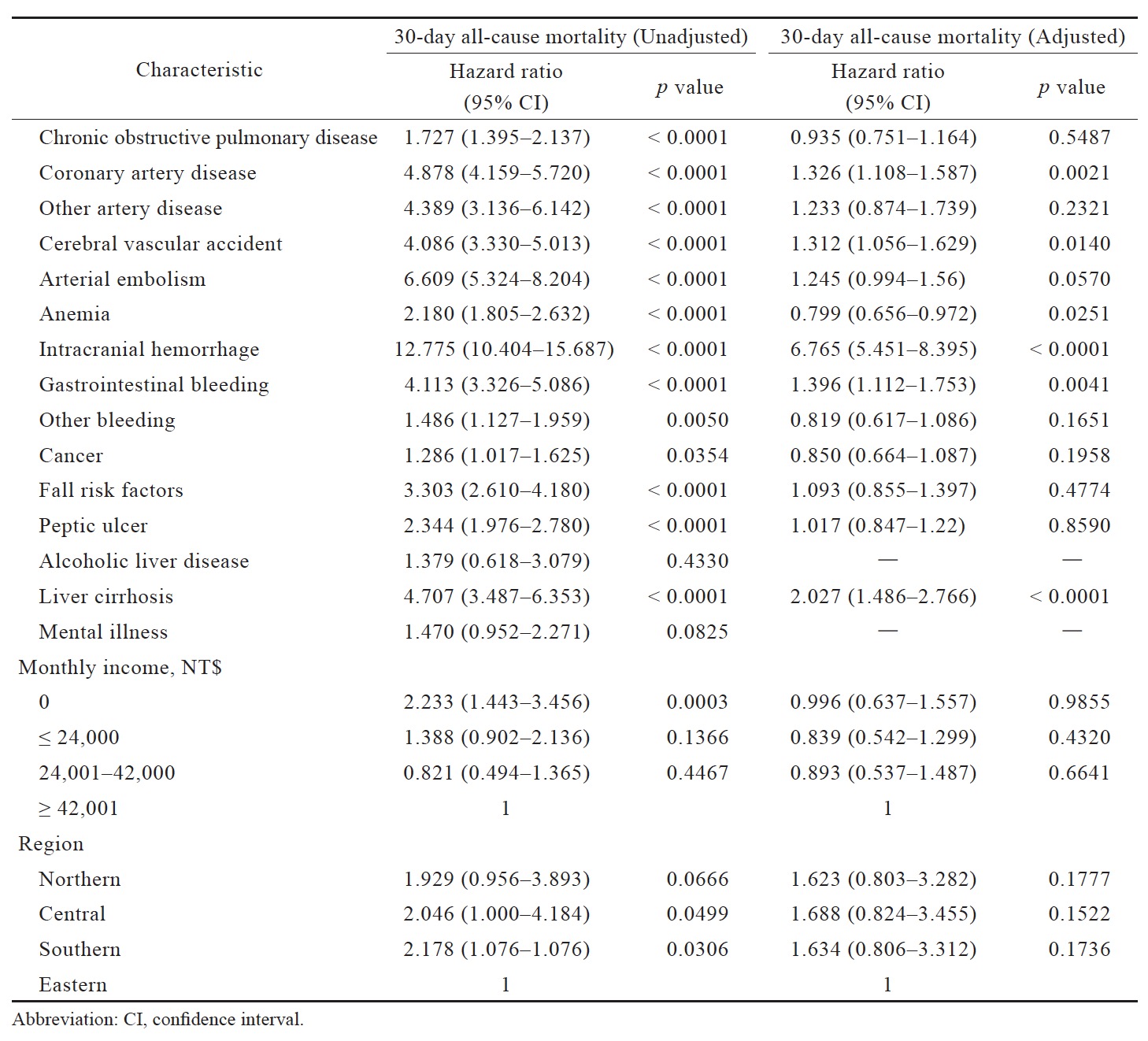

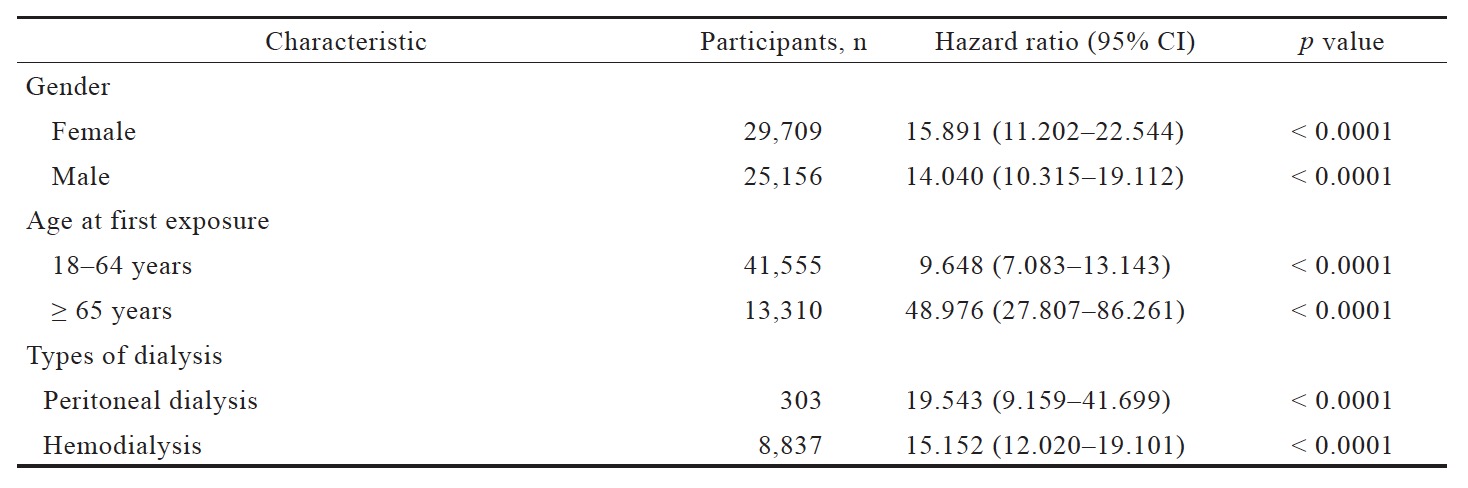

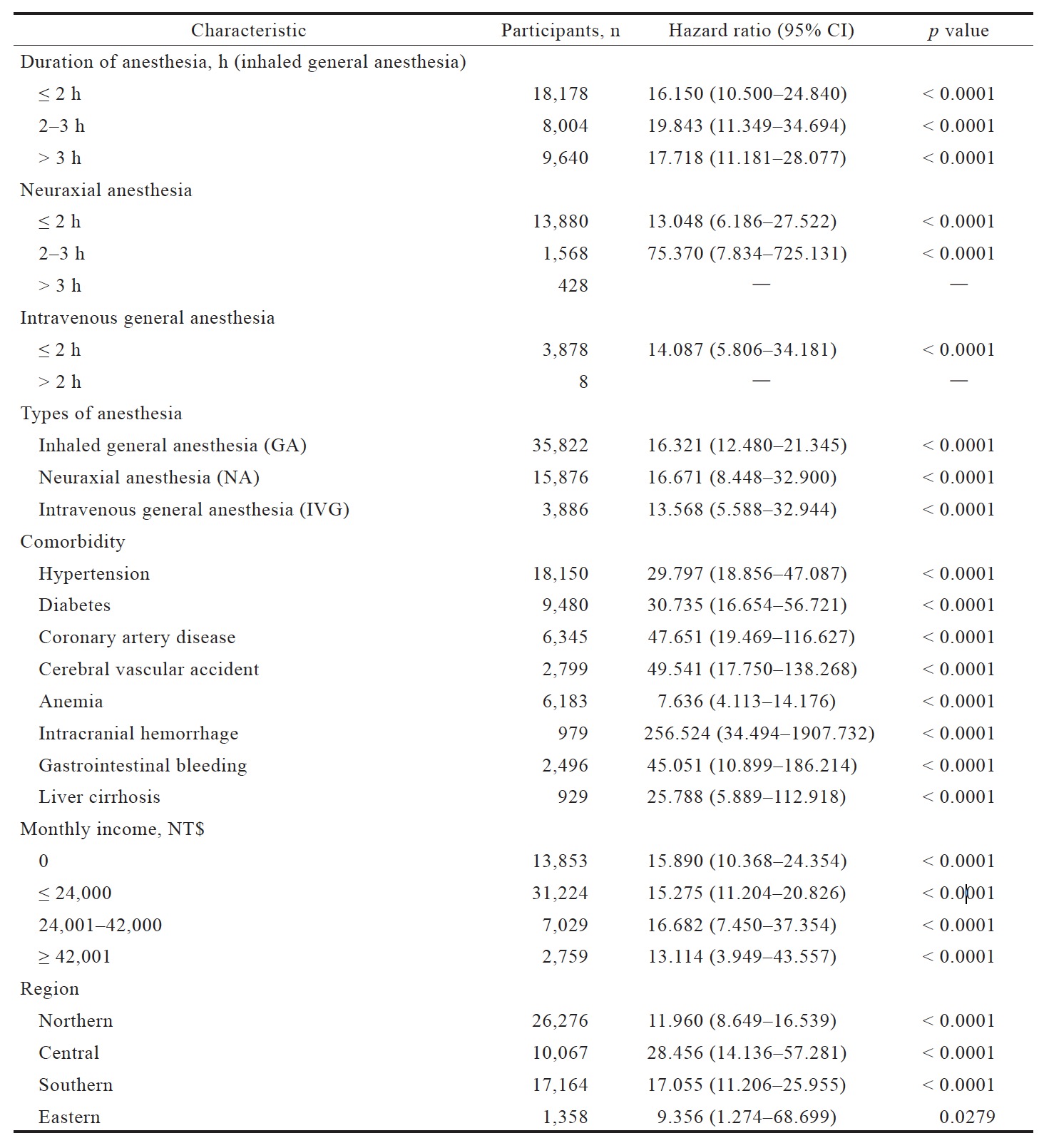

Cox regression univariable analysis was performed to determine the outcome of 30-day all-cause mortality. In Table 2, adjusted Cox regression models were performed on the dialysis cohort to calculate 30-day all-cause mortality. After univariable analysis on all covariates, statistically significant variables were selected for multivariable analysis, to determine the independent association between variable and outcome of interest. As shown in Table 3, sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the main analysis.

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Results

In this analysis, 54,865 surgery patients were included; 9,140 were on dialysis and 45,725 were not. Compared to patients in the non-dialysis group, patients in the dialysis group were more likely to be male; older; require longer general and neuraxial anesthesia duration; and have hypertension, diabetes, CHF, COPD, CAD, other artery disease, CVA, arterial embolism, anemia, intracranial hemorrhage, GI bleeding, other bleeding, cancer, fall risk factors, peptic ulcers, liver cirrhosis, and mental illness (Table 4).

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Cox regression univariate analysis demonstrated that dialysis patients had significantly higher risk for postoperative mortality (84.01/1,000 person-years) than controls (hazard ratio [HR], 15.005; 95% confidence interval [CI], 11.917–18.893) in Table 5. After multivariable analysis to adjust for baseline characteristics, the dialysis group demonstrated increased 30-day postoperative mortality within the following subgroups: male, aged patient at first surgery, long duration of inhalation general anesthesia, and comorbidities of diabetes, CHF, CAD, CVA, intracranial hemorrhage, GI bleeding, and liver cirrhosis. Dialysis patients receiving longer durations of inhalation general anesthesia had significantly higher mortality risk (HR, 1.113 ± 0.033; p < 0.0001), whereas those receiving longer durations of neuraxial anesthesia had less but insignificant changes in mortality risk (HR, 0.911 ± 0.097; p = 0.1078) (Table 2). Those results may be the combination of anesthesia drug, surgery complexity and surgical skill. Of the comorbidities, intracranial hemorrhage was associated with the highest risk of 30-day mortality (HR, 6.765; 95% CI, 5.451–8.395) (Table 2). In comparison, the other comorbidities that also significantly increased mortality gave much lower HRs, ranging from 1.232 to 1.396.

Download full-size image

Table 3 shows the results of sensitivity analysis. Postoperative mortality risk in peritoneal dialysis patients was more pronounced than in hemodialysis patients (HR, 19.543; 95% CI, 9.159–41.699 vs. HR, 15.152; 95% CI, 12.020–19.101), and in patients over 65 than under (HR, 48.976; 95% CI, 27.807–86.261 vs. HR, 9.648; 95% CI, 7.083–13.143).

Discussion

Our study found postoperative mortality differences between dialysis and non-dialysis patients, with several factors such as gender, age, anesthesia duration (HR, 1.01–1.30), and various comorbidities (HR, 1.23–6.76) contributing to postoperative mortality in dialysis patients. Comorbidities seem dominant for mortality than other factors. Consistent with previous literature,3,4,9 our dialysis patients exhibited significantly higher postoperative mortality risk than non-dialysis patients, with a relative risk of 15.0. Another study reported an adjusted odds ratio of 3.3 (95% CI, 2.56–4.33) for postoperative mortality.3 The increased mortality risk in our dialysis cohort reflects existing data on dialysis patients. Subgroup analysis showed that age contributed significantly to postoperative mortality. Another explanation is that dialysis patients possess more severe complications and comorbidities. Uremic effects—nitrogenous toxins, electrolyte accumulation, decreased erythropoietin, albuminuria, disturbed calcium and phosphate metabolism, and secondary hyperparathyroidism—may contribute increased mortality.

Multivariable analysis revealed that diabetes, CHF, CAD, CVA, intracranial hemorrhage, GI bleeding, and liver cirrhosis were independently significant risk factors for postoperative mortality in dialysis patients. Cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of ESRD death,6 manifests its effects in renal and extrarenal end organs. Of our identified comorbidities, intracranial hemorrhage accounted for the highest postoperative mortality risk (HR, 6.765). It may reflect the same underlying small vessel pathology.10 As well, uremic patients possess elevated hemorrhage risk due to coagulopathy. Compared to intracranial hemorrhage, CVA was associated with a less pronounced mortality risk (HR, 1.312), possibly because intracranial hemorrhage is a more easily image-based diagnosis, whereas CVA diagnosis can be quite subtle. A study showed that dialysis patients with intracranial hemorrhage possess high (36%) mortality rates, worsened with the presence of diabetes, malignancy, or stroke history.11 A previous study also demonstrated that warfarin use significantly increased ischemic stroke risk in dialysis patients.12 Together, these findings highlight that, for anesthesiologists and surgeons, detecting and controlling patients’ conditions in preoperative dialysis period, especially intracranial hemorrhage, are crucial.

A shorter duration of general anesthesia may decrease mortality risk in dialysis patients. There was an 11% rise in mortality risk in dialysis patients with longer durations of general anesthesia. The anesthesia duration usually present somewhat kind of surgery complexity and surgical skill. So it may be a result combined with anesthesia, surgeon skill and surgical complexity. And it is reasonable to be associated with mortality. However, for neuraxial anesthesia, the duration presented no significance in mortality increase. This may be because regional anesthesia is typically administered with relative simple and shorter surgical type. However, the true factor needs more specific studies. Meanwhile, the selection of general anesthesia or neuraxial anesthesia was usually a consensus decision by anesthesiologist, surgeon, and patient. We also did not exclude that anesthesiologists may prefer general anesthesia due to bleeding tendencies in dialysis patients or a higher payment under Taiwan insurance system. However, the significant risk associated with general anesthesia duration warrants consideration of reducing the time both in surgery and anesthesia.

The effect of general versus regional anesthesia in ESRD patients remains ambiguous. Despite the systemic effects associated with general anesthesia, renal failure is often associated with infection, anemia, bleeding tendencies, and lowered platelet function—all of which pose risks for regional anesthesia.13 Studies have found mortality benefits in using neuraxial over general anesthesia in hip surgery.6 Future studies should examine the effect of anesthesia type on mortality outcome in dialysis patients undergoing lower extremity surgeries.

Sensitivity analyses showed that postoperative mortality risk was more pronounced but not statistically significant in peritoneal dialysis patients compared to hemodialysis patients. Studies in the US, Canada, Europe, and Taiwan have shown no significant mortality difference between hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, but better survival on hemodialysis amongst older diabetic patients.14-18 Though our study uniquely examined the effect of dialysis method specifically on postoperative survival, it did not make further distinctions by age group or comorbidity.

Our study possesses several strengths. We targeted a country with the world’s highest ESRD incidence rate. Through Taiwan’s compulsory NHI, which enrolls 99% of the Taiwanese population, we had access to a national nonselective cohort of over 50,000 patients. Thus, we avoided selection bias. As well, we identified anesthesia type and comorbidities based on strictly defined ICD-9 and anesthesia codes to minimize misclassification of exposure. However, our study also contains several limitations. First, patients who underwent neuraxial anesthesia likely did not possess major contraindications to regional anesthesia compared to those who underwent general anesthesia. To account for these differences, our multivariable analysis included common comorbidities. However, we may have underestimated the prevalence of the comorbidities, and the list of comorbidities is not exhaustive. Second, surgery type did not address. However, it is hard to stratify all types of surgeries to determine their effect on postoperative mortality. And even the same surgical type may present huge difference due to different surgeons, different hospital and even different insurance policy (e.g., robotic vs. traditional, diagnosis-related group [DRG] vs. non-DRG). Studies often categorize surgeries into cardiac and noncardiac types, or by hospital department; however, even within those categories, there is still a great diversity. The anesthesia duration can present somewhat kind of surgery complexity and surgical skill. Those factors (surgery complexity and surgical skill) are also important for mortality. Nonetheless, future studies also need to adjust those surgical factors to reduce bias.

In conclusion, our population-based study supports previous literature for dialysis patients on increasing postoperative mortality. Major factors that account for elevated risk are their various comorbidities—especially intracranial hemorrhage—and long general anesthesia duration is also contributed. These results raise the importance of awareness of comorbidities in dialysis patients before operation. Surgeons and anesthesiologists are recommended to reduce anesthesia (surgical) time when general anesthesia is administered.

Acknowledgments

We would like to give our great thanks to Dr. Tzu-Chieh Lin (Adjunct Assistant Professor, Institute of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan) for his statistics support and Hung-Chun Chen (Master, Department of BioMedical Engineering, National Yang Ming University, Taiwan) for providing the valuable and constructive SAS program on this study. The research fund was partially supported by the National Cheng Kung University and Delta Electronics, Inc. Co-Research program (NCKU-DELTA 2014). The authors claim no conflict of interest in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Winnie Wei-Chieh Wang wrote the manuscript, Meng-Ling Li and Wei-An Chen adjusted the research project, Jeffrey Chi-Fei Wang and Hung-Tsung Hsiao provided the clinical view and Yen-Chin Liu designed the whole idea and revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors claim that there is no conflict of interest in the manuscript.

References

| 1 |

Wetmore JB, Collins AJ.

Global challenges posed by the growth of end-stage renal disease.

Ren Replace Ther. 2016;2(1):15.

|

| 2 |

Bechtel JF, Detter C, Fischlein T, et al.

Cardiac surgery in patients on dialysis: decreased 30-day mortality, unchanged overall survival.

Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(1):147–153.

|

| 3 |

Cherng YG, Liao CC, Chen TH, Xiao D, Wu CH, Chen TL.

Are non-cardiac surgeries safe for dialysis patients?—a population-based retrospective cohort study.

PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58942.

|

| 4 |

Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Kile D, Robinson TN, Henderson WG.

Risk of major nonemergent inpatient general surgical procedures in patients on long-term dialysis.

JAMA Surg. 2013;148(2):137–143.

|

| 5 |

Carlo JO, Phisitkul P, Phisitkul K, Reddy S, Amendola A.

Perioperative implications of end-stage renal disease in orthopaedic surgery.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(2):107–118.

|

| 6 |

Hopkins PM.

Does regional anaesthesia improve outcome?

Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(suppl 2):ii26–ii33.

|

| 7 |

Kettner SC, Willschke H, Marhofer P.

Does regional anaesthesia really improve outcome?

Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(suppl 1):i90–i95.

|

| 8 |

Hsieh CY, Cheng CL, Lai EC, et al.

Identifying renal dysfunction in stroke patients using diagnostic codes in the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database.

Int J Stroke. 2015;10(1):E5.

|

| 9 |

Birjiniuk V.

Patient outcomes in the assessment of myocardial injury following cardiac surgery.

Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(6):S2208–S2270.

|

| 10 |

Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Breteler MMB.

Decreased glomerular filtration rate is a risk factor for hemorrhagic but not for ischemic stroke: the Rotterdam Study.

Stroke. 2007;38(12):3127–3132.

|

| 11 |

Lin CY, Chien CC, Chen HA, et al.

The impact of comorbidity on survival after hemorrhagic stroke among dialysis patients: a nationwide population-based study.

BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:186.

|

| 12 |

Chen CY, Lin TC, Yang YHK.

Use of warfarin and risk of stroke and mortality in chronic dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation in Taiwan.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:457–458.

|

| 13 |

Craig RG, Hunter JM.

Recent developments in the perioperative management of adult patients with chronic kidney disease.

Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(3):296–310.

|

| 14 |

Chien CC, Wang JJ, Sun YM, et al.

Long-term survival and predictors for mortality among dialysis patients in an endemic area for chronic liver disease: a national cohort study in Taiwan.

BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:43.

|

| 15 |

Vonesh EF, Snyder JJ, Foley RN, Collins AJ.

The differential impact of risk factors on mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

Kidney Int. 2004;66(6):2389–2401.

|

| 16 |

Noordzij M, Jager KJ.

Survival comparisons between haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(9):3385–3387.

|

| 17 |

Huang CC, Cheng KF, Wu HD.

Survival analysis: comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in Taiwan.

Perit Dial Int. 2008;28(suppl 3):S15–S20.

|

| 18 |

Chang YK, Hsu CC, Hwang SJ, et al.

A comparative assessment of survival between propensity score-matched patients with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in Taiwan.

Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(3):144–151.

|