Abstract

Objective

Postdural puncture headache (PDPH) is the most common serious complication in obstetric anesthesia. We show the incidence of accidental dural puncture (ADP), PDPH, epidural blood patch (EBP) and associated morbidity following a protocol established in an obstetric anesthesia department.

Methods

An observational, prospective, analytical study performed in 66,540 epidural labor analgesia procedures. The objective is to describe the incidence of ADP, PDPH and EBP in a large obstetric anesthesia population, as well as morbidity associated with ADP and EBP.

Results

Incidence of ADP and PDPH was 0.76% and 59%, respectively, and the global incidence of EBP was 0.2%. Experience of the anesthetist performing the epidural (1st or 2nd year resident) and night shift were correlated with ADP. Low back pain was more frequent in patients undergoing EBP.

Conclusion

We found an incidence of ADP and PDPH of 0.76% and 59%, respectively. Experience of the anesthetist performing the epidural (1st or 2nd year resident) and night shift were correlated with ADP. EBP is a safe, easy and acceptable treatment for PDPH, despite a higher risk of low back pain

Keywords

obstetric accidental dural puncture; postdural puncture headache; risk factors; protocol; epidural blood patch;

1.Introduction

Accidental dural puncture (ADP) and subsequent postdural puncture headache (PDPH) are known complications of neuraxial anesthesia. Despite the prevalence of this condition, relatively little is known about its pathophysiology, and few accepted treatments are evidence-based. In obstetric patients, ADP occurs at a rate of 0.18%–6%, and approximately 50%–70% of these develop PDPH.1,2

Strategies proposed to prevent PDPH after ADP include intrathecal insertion of the epidural catheter,3 early epidural blood patch (EBP)4 and epidural saline injection,5 but these have shown limited efficacy. Little is known about the best prophylactic treatment for PDPH.6 However, therapeutic EBP is considered the gold standard for treatment.7

Our aim was to describe the incidence and risk factors of ADP, PDPH and EBP in a large obstetric anesthesia population, as well as the safety, feasibility and tolerability of treatment with EBP. We present a written protocol for the management and monitoring of patients presenting ADP.

2.Methods

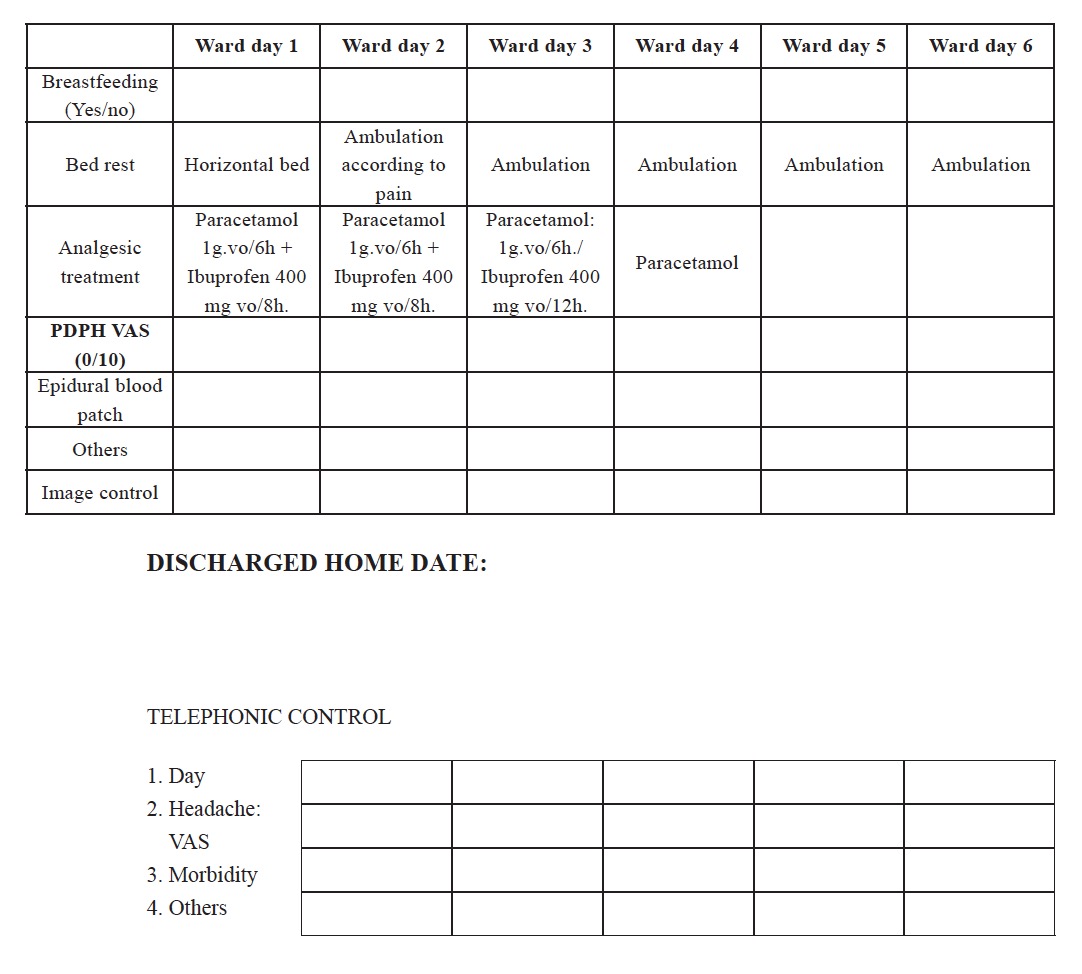

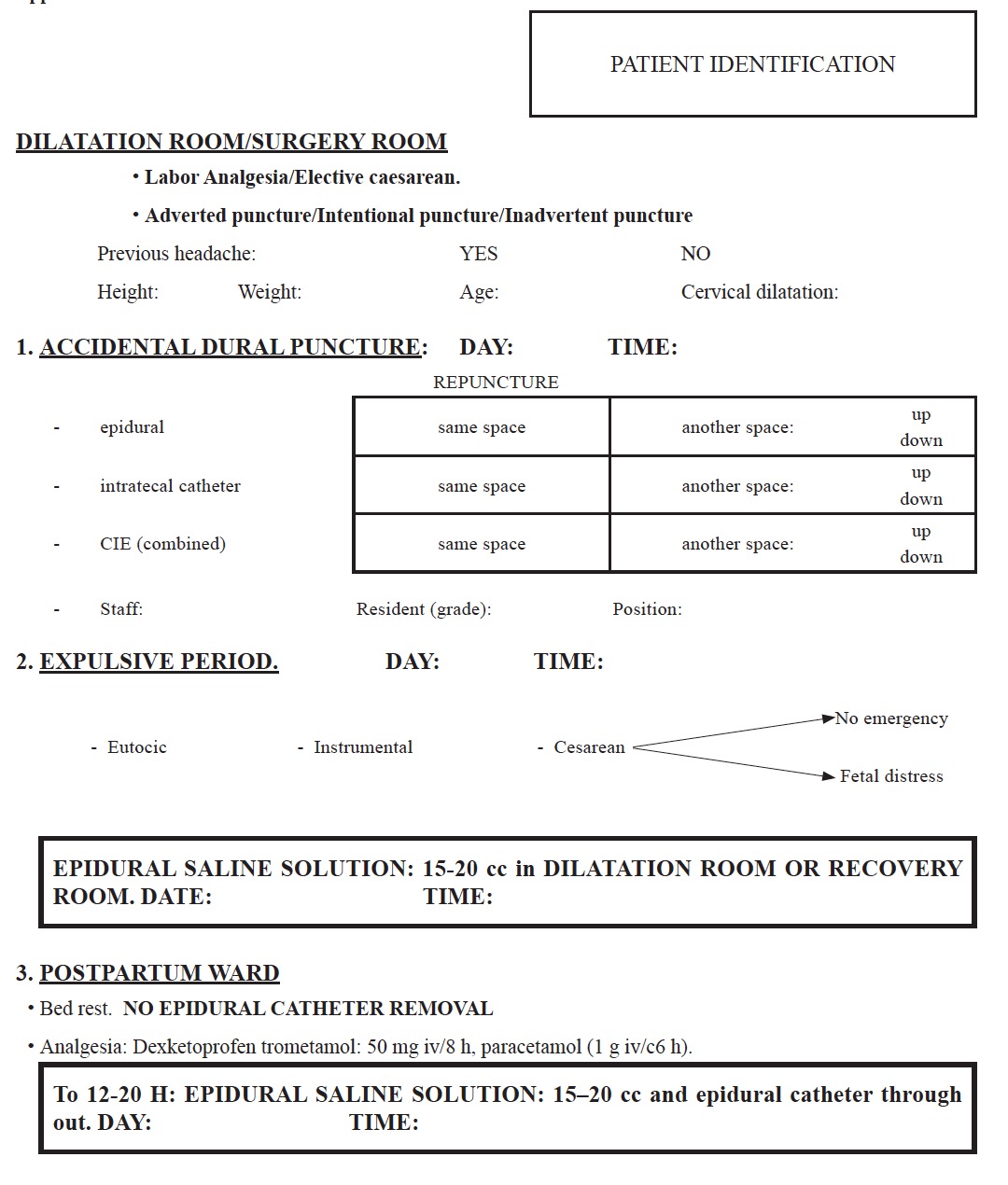

We performed a prospective, observational, analytical and descriptive study in all parturients experiencing ADP during epidural analgesia for labor performed in our maternity unit. The study was carried out between June 2001 and October 2012 following approval from the research ethics committee (Hospital La Paz, Madrid; HULP code: PI-2107). Patients were managed using a departmental protocol for post-ADP analgesia management, which is standard practice in our hospital (Appendix 1).

Inclusion and Exclusion CriteriaInclusion criteria for the study were: (1) women with labor pain who provided their informed consent for epidural analgesia; (2) parturients who delivered during the study period, and had a known dural puncture. Women undergoing elective caesarean section with epidural anesthesia were excluded from the study.

ProtocolThe epidural block was performed for women in labor. The epidural catheter was placed to provide labor analgesia, and patients with scheduled caesarean section were excluded. Final delivery was either vaginal, with forceps, or by caesarean section. The main indications for caesarean section in these patients were cephalopelvic disproportion, failure to progress (incomplete dilation of the cervix, slow or stalled labor, or abnormal positioning of the baby) and fetal distress. Women scheduled for caesarean section were not included in this study.

After the patient with labor pain had been examined by the midwife, all procedures were performed in the sitting position.

ADP was defined as objective loss of cerebrospinal fluid through the Tuohy needle during performance of epidural block.

Two types of catheter were used: a Perisafe Plus® (Becton Dickinson and Company, Mönlycke Health Care, Göteborg, Sweden) epidural analgesia kit with a 18G Tuohy needle, and an Espocan® (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) combined spinal epidural anesthesia system with Perifix® (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) soft tip catheter (18G Tuohy needle and 27G intradural needle) and docking system. The epidural space was identified using the loss of resistance to air technique.

The anesthesia technique was performed by anesthesia residents (1st to 4th year) and by anesthesia staff.

The 24-h period observation period was divided into 3 shifts: 8:00–15:00 (shift 1), 15:01–22:00 (shift 2) and 22:01–7:59 (shift 3).

Once ADP was detected, the epidural analgesia catheter was re-sited in a superior interspace at the first attempt and properly secured. Correct location of the epidural catheter was confirmed by administration of 3 mL bolus of bupivacaine 0.25% with epinephrine, and the first analgesic dose was fractionally administered: 9 mL levo-bupivacaine 0.25% and 20 μg fentanyl, after which an epidural infusion pump (HospiraGemStar infusion pump blue, Pacific Medical, Tracy, CA, USA) was connected (0.125% levo-bupivacaine + 1.2 μg fentanyl for each mL, 8–11 ml/h) with the possibility of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) (8–11 mL, 15 minute lockout range).

Regardless of the mode of delivery (vaginal, instrumental or caesarean), an epidural injection of 20 mL saline 0.9% was administered immediately after delivery and also 12–20 hours later, and the epidural catheter was removed. All patients received an epidural injection of saline. No special management during the second stage of labor was considered in ADP patients (instructions not to push, instrumental delivery to alleviate active pushing).

During the first 24 hours after labor, postpartum pain was controlled with intravenous (iv) paracetamol 1 g every 6 h and iv dexketoprofen trometamol 50 mg every 8 h. Patients who underwent a caesarean section also received a 2 mg bolus of epidural morphine.

Using International Headache Society guidelines, we defined PDPH as a positional headache that worsened on sitting and/or standing, and that improved when adopting the decubitus supine position, with at least 1 of 5 accompanying symptoms (nuchal rigidity, tinnitus, hypoacusia, photophobia, nausea, diplopia).8

During this period, the presence of PDPH was evaluated and associated symptoms were recorded. If conservative treatment failed, the patient was offered an EBP. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. After 48 hours of persistent PDPH with a visual analogic scale (VAS) score > 7/10, an EBP was performed (15–20 mL or until the patient reported low back pain). The patients remained supine for 1 h. If the EBP was not effective (headache persists for 48 h),we repeated the EBP procedure using the same technique. The first and second epidural puncture for EBP was performed by staff of the anesthesia department, preferably in the same intervertebral space where the dural puncture occurred. An additional image test (magnetic resonance) was required after a second unsuccessful EBP.

All patients were followed up with a telephone call 1 week and 3 months after the dural puncture, and were advised to contact the anesthesiology department if headache symptoms persisted. ADP-induced morbidity was recorded: low back pain, chronic headache and radiculopathy. We also recorded the need of additional image tests and the presence of other symptoms, such as tinnitus or diplopia.

Previous history of tensional headaches or migraines was recorded.

All patients were instructed to contact the anesthesia department if PDPH developed or worsened at any time thereafter.

Statistical AnalysisQuantitative continuous variables were described as mean plus standard deviation. Categorical variables were described as absolute frequencies, and relative frequencies were expressed in percentages. Quantitative variables between independent groups were compared primarily using parametric tests (for continuous data), paired samples Student’s t test, or analysis of variance (ANOVA) when 3 or more groups were involved. If, as a result of stratification, groups had 30 cases or less, statistical significance was obtained by non-parametric tests, Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney. Frequency analysis between qualitative variables was performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as required (if n < 20, or if any value in the table of expected values was less than 5). We used the chi-square test with Yates correction. A multivariate analysis using logistic regression was planned, if applicable, to identify independent risk factors for ADP.

3.Results

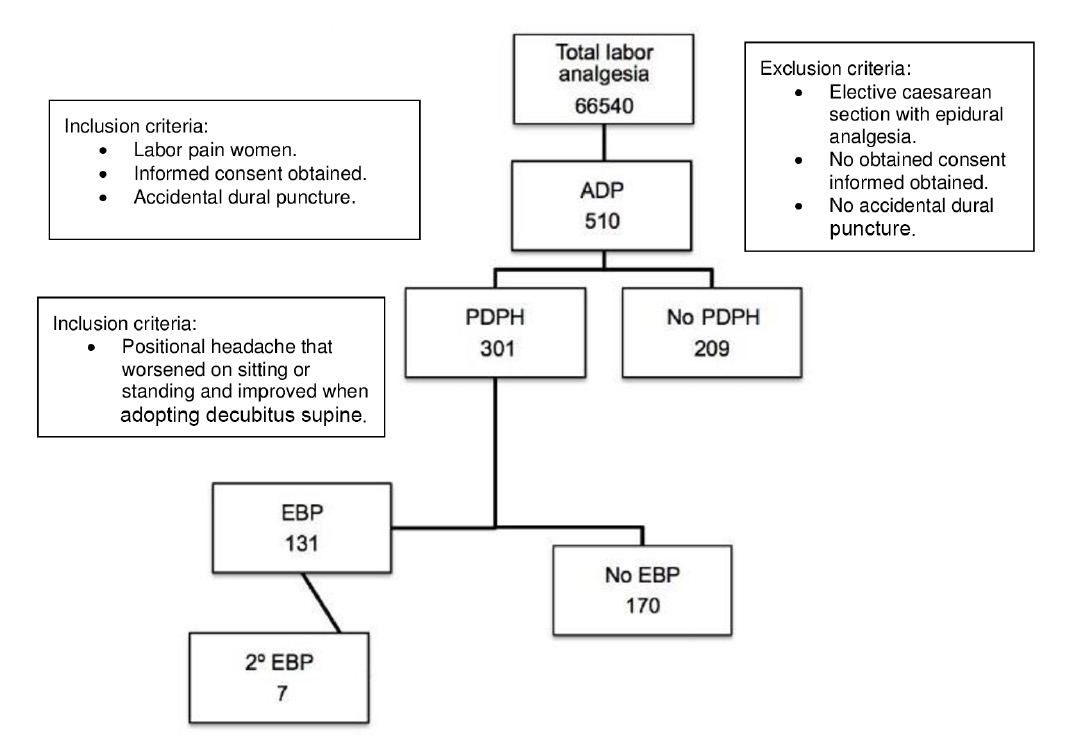

From June 1, 2001 until October 31, 2012, 66,540 epidurals for labor analgesia were performed. Fig. 1 shows the study flow chart. Of the 66,540 epidurals performed, ADP occurred in 510, giving a cumulative incidence of 0.76%.

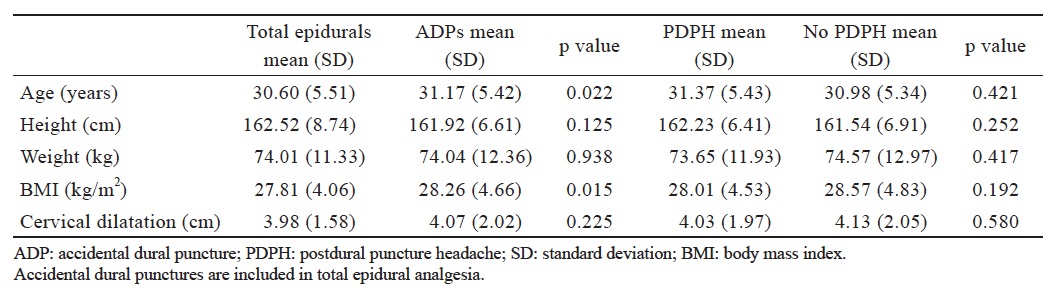

able 1 summarizes patient demographics, showing the total number of epidurals performed and the number of ADPs. ADP was more frequent in older patients with higher body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.015).

Download full-size image

Total labor analgesia: all the women having epidural analgesia for labor pain.

We found no association between the degree of cervical dilatation and the risk of ADP and PHPD, respectively. The mean (SD) for cervical dilatation at epidural insertion was 3.81 (1.83). ADPs were more common among junior anesthesia residents (p < 0.001) working on the night shift (shift 3) (Table 2 ).

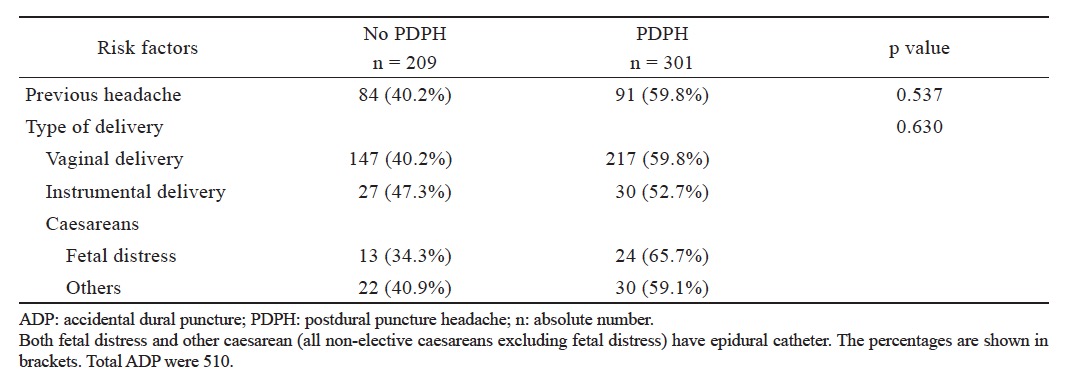

Slightly over half (59%) of patients with ADP presented PDPH. There were no statistically significant demographic differences between parturients presenting and not presenting PDPH (Table 1 ). Previous history of headache (migraine or tension headache) was not considered a risk factor for PDPH (59.9% vs. 59.8%, p = 0.53), neither was type of delivery, as shown in Table 3 .

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

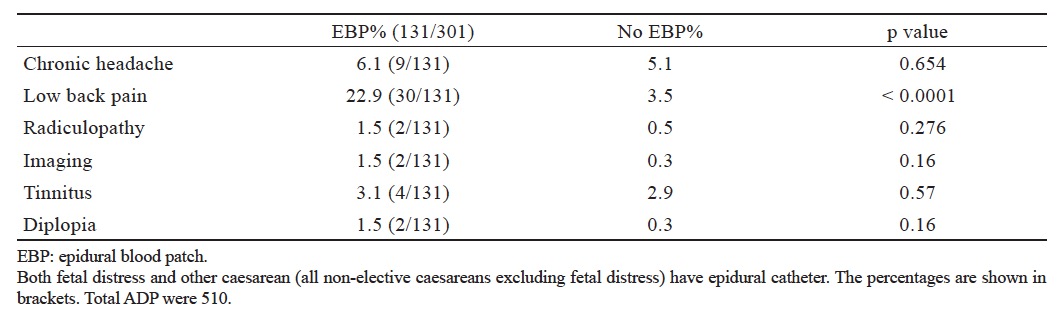

Of the 510 patients presenting ADP, 131 (25.7%) underwent EBP. Of patients undergoing EBP, the procedure was repeated due to persistent headache in 5.3%. Overall EBP rate was 0.2%. Of total parturients with severe PDPH (VAS > 7), 37% refused EBP and preferred to wait until the headache resolved. Therefore, 72% of patients with headache lasting more than 10 days did not undergo EBP.

Long-term back pain and chronic headache were the most frequent morbidities in the EBP population. There were no differences between patients undergoing EBP and those that did not in terms of side effects, such as additional imaging tests performed due to changes in type of headache, onset of tinnitus or diplopia (Table 4 ). More patients undergoing EBP were readmitted to hospital (8.4% vs. 0.5%, p < 0.001), mainly for PDPH.

Download full-size image

We studied a large population of patients who received epidural analgesia for labor and, specifically, those who experienced ADP. The protocol applied provides PDPH prophylaxis in all confirmed ADPs, with 2 epidural saline patches, 1 performed at the end of expulsive period, and the other 12–20 hours after delivery. Incidence of ADP was 0.76% (66,540 epidurals for labor).

Incidence of ADP in our study is consistent with the literature.1,2 Air was always used in the loss of resistance technique, even though PDPH incidence may differ when saline is used. Other studies have shown that risk of ADP is not related to the medium used for the loss of resistance technique.9

We found that BMI and age were positively correlated with ADP. Faure et al.10 showed that incidence of ADP was approximately 4% in morbidly obese vs. 0.25%–0.5% in non-morbidly obese parturients (p < 0.05).

It is important to point out that we found no correlation between degree of cervical dilatation and risk of ADP in our study population (66,540 epidural procedures). However, risk of ADP increased during night shifts, and unlike Hollister et al.11 we also found a significant correlation between the experience of the anesthetist and occurrence of ADP (p < 0.001).

When interpreting our findings, it is important to bear in mind that all epidurals were performed if the parturient reported labor pain, even though the VAS pain score was not recorded at the time of epidural puncture.

Incidence of PDPH was 59%; this is consistent with previous studies (50%–81% in pregnant women). 3 PDPH was not correlated with either BMI or age; this is also consistent with other reports.12 Hood et al.13 and Peralta et al.14 showed that incidence of PDPH was significantly higher in non-morbidly obese vs. morbidly obese parturients, but found no evidence to correlate ADP with age.

Incidence of PDPH did not differ between women with and without previous migraine headache.15 The type of delivery did not determine appearance of PDPH, in contrast to other studies where the Valsalva maneuver worsened the headache.16 Peralta et al. suggested an association between pushing during labor and an increased likelihood of PDPH after ADP.14

Furthermore, patients undergoing caesarean were given 2 mg of epidural morphine to control acute postoperative pain; however, no significant difference in PDPH rate was observed in patients receiving epidural morphine.17

The global incidence of EBP was 0.2%. This is lower than that reported in other studies,10,13 and may be due to the use of prophylactic epidural saline injection during the postpartum period. The EBP rate in patients with ADP was 25.7%, and 5.3% underwent a second EBP; this is consistent with the findings of Baysinger et al.18 Furthermore, 37% of patients with severe PDPH declined EBP, despite a VAS score > 7/10.

The fact that few institutions have a written protocol for managing ADP is indicative of the heterogeneous approach to ADP and PDPH management and the lack of evidence on PDPH prevention. In our protocol, EBP has always been used to treat PDPH, and never as prophylaxis.19 It has always been performed 48 hours after ADP, because higher failure rates have been reported with early rather than delayed EBP.20

There is as yet no ideal strategy for preventing ADP-induced PDPH. Many options have been put forward, but results have been disappointing.21 One of the methods used in the treatment of PDPH is intrathecal epidural catheter insertion, but there is significant controversy in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of this approach. Early EBP has been associated with neurological complications.22 Some authors have shown that epidural saline injections have a lower success rate than EBP, while others have suggested the epidural saline patch as an alternative strategy to EBP for PDPH; there is no clear consensus on which prophylactic measure is the most effective.

The most aggressive measure within the protocol was EBP, and for this reason we studied the longterm repercussions of this intervention. In terms of morbidity, telephone follow-up 10 days and 3 months after the procedure showed that low back pain was the most common finding. Incidence of low back pain was significantly higher in patients undergoing EBP. This contrasts with other authors who found that incidence of low back pain did not increase in women undergoing EBP,23 but is consistent with Kakinohana et al.,22 who reported that low back pain was more frequent in patients who underwent EBP. Low back pain can occur in postpartum women not receiving epidural analgesia; and therefore this finding should be viewed with caution. The hospital readmission rate was higher in patients who underwent EBP, but not in those reporting diplopia, tinnitus, or those requiring complementary imaging tests due to erratic PDPH course.24

With these data and the implementation of our protocol,25 we would emphasize that during follow up of all patients, including those undergoing epidural saline patches or EBP, no serious complications were reported, although incidence of low back pain was more common (23%) in the EBP group.

his study has several limitations. Firstly, it is observational. Secondly, anesthetists performing the technique had different levels of experience, ranging from anesthesia residents to obstetric anesthesia consultants, which could be a source of bias; nevertheless, we tried to reproduce the normal conditions encountered in clinical practice.

We believe that ADP also occurs in different clinical circumstances, but this is one of the largest studies performed in women with labor pain, ADP and EBP following a written protocol to optimize and monitor associated morbidity.

Our findings are important insofar as they show the incidence of ADP (despite working in a teaching hospital, our results indicate that incidence is low), EBP-induced morbidity (in a large sample of EBP patients), and propose a protocol for the management of ADP.26

Also, the risk of bias is more important in an observational study than in a controlled study, and that the bias can be limited by the use of a multivariate analysis with logistic regression, when applicable. However, in our study, the bivariate analysis only identified one statistically significant risk factor for ADP: the experience of the anesthesiologist who performed the blockade. None of the possible confounding factors available showed a statistically significant association. So, we estimated that multivariate analysis could be irrelevant in this context.

4.Conclusion

We found an incidence of ADP and PDPH of 0.76% and 59%, respectively. Experience of the anesthetist performing the epidural (1st or 2nd year resident) and night shift were correlated with ADP. Implementation of standardized protocols is of maximum importance to monitor and manage ADP and PDPH. EBP is a safe, easy and acceptable option to treat PDPH, despite a higher risk of low back pain.

5.Acknowledgements

The first author would like to thank all the obstetric anesthesia staff and the residents.

Appendix

Download full-size image