Abstract

Background

Lumbar epidural injections have been studied as symptomatic treatments for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS). However, results about their efficacy have been controversial, and data regarding their use is scarce. Our purpose in this article is to study the efficacy of epidural injections in the management of pain and disability in patients suffering from spinal stenosis, to study the factors which can affect their efficacy, and to discuss whether they could replace surgery or not.

Methods

A retrospective study between 2021 and 2022 took place in a Pain Clinic located in Notre-Dame des Secours University Hospital-Lebanon. The study was done on 128 patients, of whom 18 were excluded because they underwent laminectomy before taking the transforaminal lumbar epidural injections. Medical records were viewed. Outcome measures were checked before and after epidural injections using the numerical pain scale and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scale. Physical activity was assessed with a physical activity index.

Results

Back pain scores (9.46 ± 1.07 vs. 3.91 ± 3.13;

Conclusion

Epidural injections are effective in the management of back and leg pain associated with LSS and in improving patients’ disability. Engaging in activities like walking and swimming is associated with better results. In some cases, epidural injections may replace surgery.

Keywords

back pain, epidural injections, leg pain, lumbar spinal stenosis, pain

Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a pathological condition that primarily affects the elderly. It is described as the narrowing of the neuroforamina and/or the lumbar canal and/or the lateral recesses.1

In the majority of cases, LSS results from multiple degenerative processes such as intervertebral disc protrusion, hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, the formation of osteophytes, and a thickened facet capsule2; All of this leads to mechanical compression and nerve inflammation. Less frequently, LSS can be not only caused by a congenitally narrow canal, but also the result of a traumatic or iatrogenic injury.3

The clinical presentation of LSS can vary depending on the type of stenosis. Usually, it presents with back pain. Patients may also have buttock and leg pain and paresthesia due to radicular compression at the level of the lateral recess. The compression of the thecal sac can cause neurologic claudication, which manifests as weakness during ambulation.4 Pain intensity from LSS is increased by spinal extension, ambulation, and prolonged standing. Leg vein thrombosis, infections, dural tears, and hematoma in the epidural space can complicate the surgical treatment of LSS. Patients may still have residual symptoms even after being operated on.5

Epidural injections have been studied in the management of LSS. In a retrospective study conducted to evaluate the efficacy of epidural injections in treating pain due to lumbar stenosis or herniated disks, this study concluded that half of the patients were temporarily relieved. However, only 25% of patients had long-term relief.6 In another retrospective study, it was found that epidural injections of steroids through the translaminar approach are an efficacious method for the treatment of pain and disability in patients with lumbar canal stenosis. Moreover, patients with a lower age and lower BMI improved better7. However, another retrospective study conducted in patients with LSS concluded that many of their patients had improved function and alleviated pain years after the intervention was done.8

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, there was no clear effect of epidural corticosteroid injections on pain or physical disability in patients with spinal stenosis.9

However, another meta-analysis suggests that the use of epidural corticosteroid injections is associated with limited short-term and long-term benefits for patients with LSS.10 A retrospective study conducted in an outpatient pain center concluded that, in a 10-year span, the majority of patients who were treated with epidural injections instead of surgery, had no significant clinical deterioration, and delayed surgery was of as much benefit as immediate laminectomy.11 Another study suggests that transforaminal epidural steroid injections have no impact on the need for surgery in the long term.12 A study about the efficacy and predictability of epidural steroids in LSS suggested that being female and young was predictive of better results, whereas body mass index (BMI) had no predictive value.13 A systematic review that enrolled patients with LSS in several types of physical exercise, affirmed that physical activity is associated with decreased pain and disability in those patients.14 There was also a retrospective cohort study which had the same conclusion about the association between physical activity and decreased pain after injection. It also added that patients with low socioeconomic status have more pain alleviation.15

Given the controversial results about the efficacy of epidural injections in LSS and the absence of clear guidelines for their use, we have decided to study the efficacy of epidural injections as a symptomatic treatment for LSS and their correlates, and the possibility that these injections could delay the surgical approach.

Methods

Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies was in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013) and was approved by the ethics committee of the Notre-Dame de Secours University Hospital (CHUNDS).

Our study is a retrospective study conducted in a pain center located at Notre-Dame des Secours University Hospital-Lebanon. During data collection, we contacted 128 patients with LSS, which was confirmed by MRI, who have already received, between 2021 and 2022, at least three ultrasound or X-ray guided transforaminal lumbar epidural injections. No other medical or surgical interventions were made. All the transforaminal lumbar epidural injections were done by a highly trained anesthesiologist. Each injection contained 8 mg of dexamethasone, and 10 mL of lidocaine 1%, which is the FDA approved dose, because of its anesthetic action, without causing motor nerve blocks. Patients who were operated on for LSS before taking epidural injections were excluded from the study (n = 18 patients), making the sample size 110. Patients were contacted through text messages or phone calls; they were given explanations about the study and its main objectives, and those who agreed to participate were asked to fill out a questionnaire.

Pain was evaluated using the numerical pain scale, and disability was evaluated using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). The ODI scale has been used to assess physical functioning in a wide variety of spinal diseases. ODI scale includes questions about pain intensity, ability to perform everyday activities (washing, dressing, etc.), ability to lift objects, sit, walk, stand, effect on sexual life, social life, travelling, and sleeping. The score ranges from 0 to 100. Higher scores are associated with worse pain and disability. The numerical pain scale ranges from 0 to 10, and higher values signify worse pain (Cronbach’s alpha in this study = 0.89).

The numerical pain scales (for back and leg pain) and the ODI scale were assessed prior to and 12 to 24 months following the completion of a minimum of three transforaminal lumbar epidural injections.

The primary outcome is the change in back and leg pain and in the patient’s disability before and 12 to 24 months after a minimum of three lumbar epidural injections were administered. The secondary outcome is evaluating factors associated with the change in scores after epidural injection. The tertiary outcome is to see how many people benefited from the injections without the subsequent need for surgery during the period of our study.

The minimal sample size was calculated using G-power software; based on a previous study7 that showed an improvement of the ODI scores from 57.2 ± 11.0 to 33.4 ± 15.0 and taking an alpha risk of error of 5% and a power of 95%, the minimum sample size needed was 20.

Information concerning age, gender, BMI, medical, and surgical history during the period of receiving the injections, duration of symptoms, number of injections, and LSS level(s) were extracted from medical records after the patient’s approval was obtained. A section was added to specify if they eventually needed laminectomy even after taking the injections or not.

The questionnaire included the following sections: written consent, other sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, including education level, household crowding calculated by dividing the number of persons by the number of rooms in the house16, and the three questions of the physical activity index (intensity, frequency, and duration).17 Furthermore, the patient self-reported a numerical pain scale for back and leg pain before and after the injections.

For the statistical evaluation of the data, we used SPSS version 25 for windows. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for reliability analysis. The data was presented as mean ± standard deviation. To compare outcomes before and after the injections, we used a paired

Results

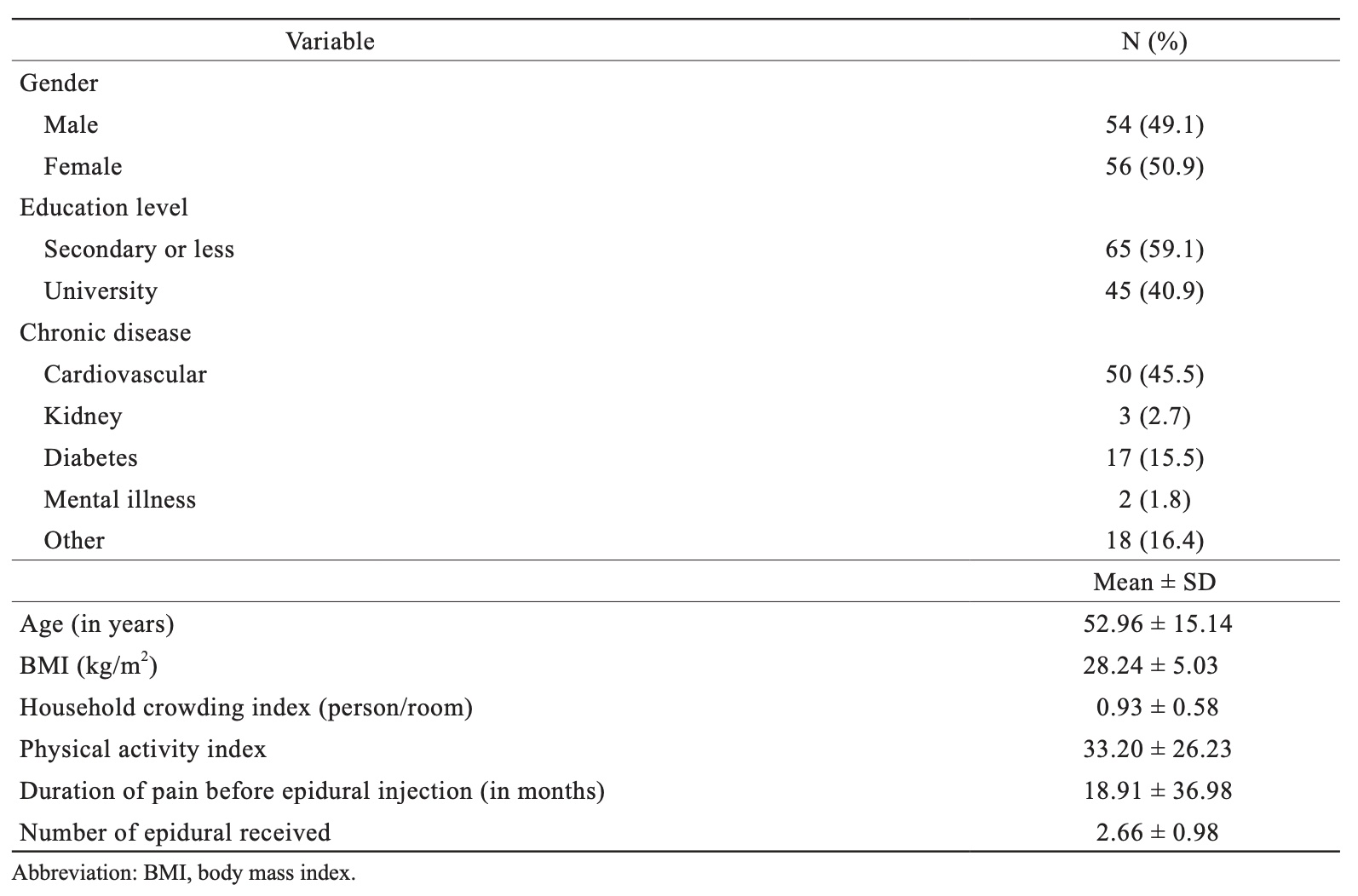

The mean age of the 110 participants was 52.96 ± 15.14 years while their mean BMI was 28.24 ± 5.03 kg/m2, with 50.9% being females. Other characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

In 57.8% of the patients, epidural injections were sufficient for pain management without the need for surgery.

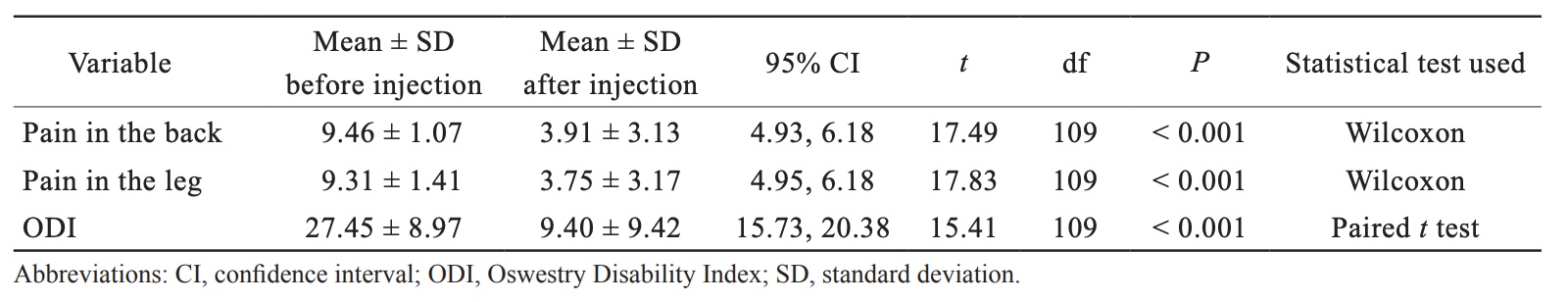

The mean pre-injection numerical pain score for the back is 9.46 ± 1.07, which improved to 3.91 ± 3.13 post-injection (

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

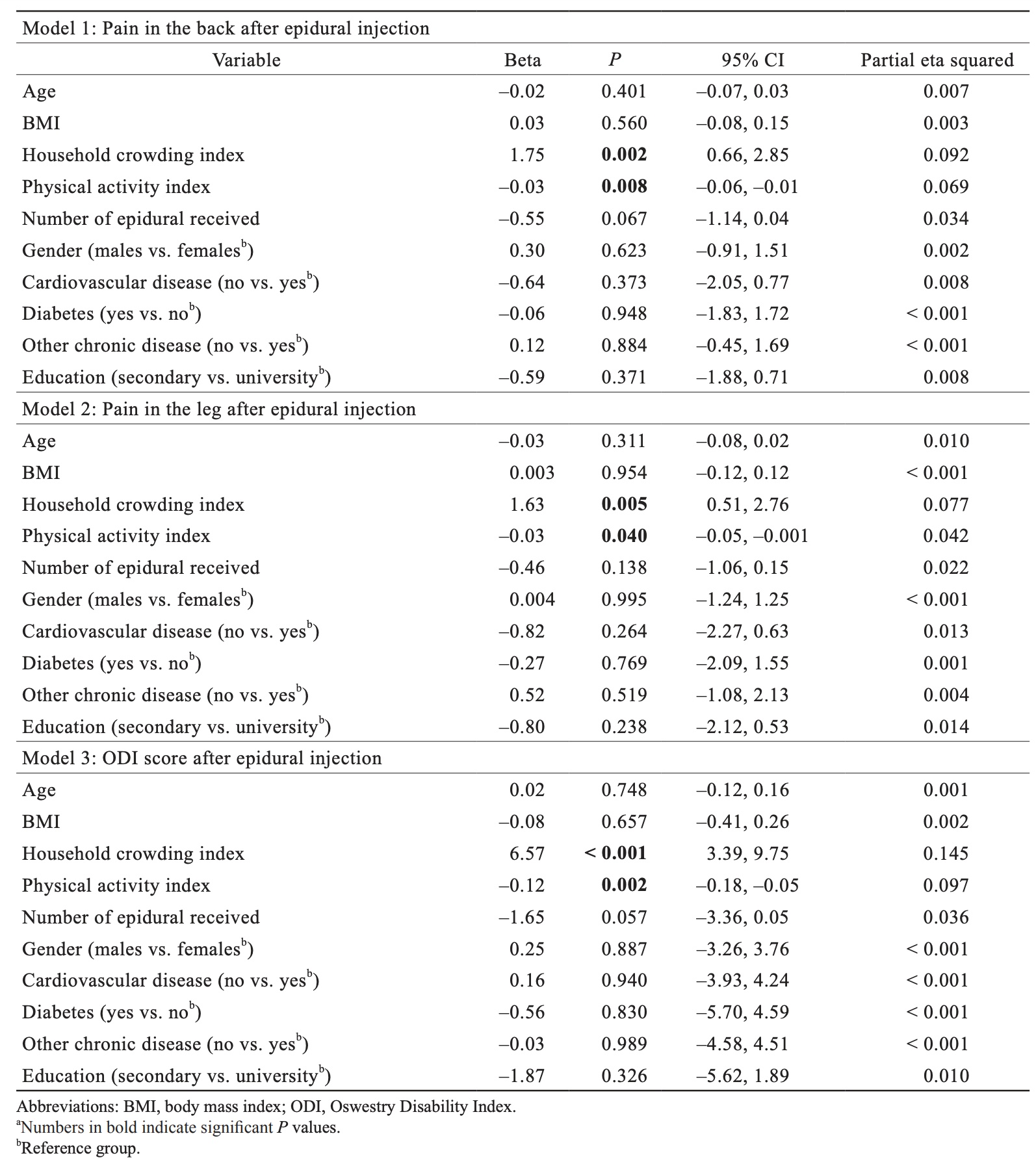

A higher household crowding index (Beta = 1.75) was significantly associated with an increase in back pain scores after taking epidural injections, whereas a higher physical activity index (Beta = –0.03) was significantly associated with a decrease in back pain scores after taking epidural injections (Table 3, Model 1).

A higher household crowding index (Beta = 1.63) was significantly associated with an increase in leg pain scores after taking epidural injections, whereas a higher physical activity index (Beta = –0.03) was significantly associated with a decrease in leg pain scores after epidural injections (Table 3, Model 2).

A higher household crowding index (Beta = 6.57) was significantly associated with an increase in ODI scores after taking epidural injections, whereas a higher physical activity index (Beta = –0.12) was significantly associated with a decrease in ODI scores after taking epidural injections (Table 3, Model 3).

Download full-size image

Discussion

Our data suggests that lumbar epidural injections of dexamethasone and lidocaine, successfully decrease pain and disability in patients with LSS. First, their efficacy is due to the potent anti-inflammatory action of dexamethasone, which reduces local inflammation in the lumbar canal and alleviates nerve irritation and spinal canal compression. Second, the analgesic effect of lidocaine, which blocks pain pathways in the lumbar spine, accounts for their effectiveness. The pain intensity can fluctuate in the same patient; pain-free and painful periods may alternate depending on the level of physical exertion of the patient and his lifestyle. There is no definite remission status, but according to our study, the pain and disability are significantly reduced, 12–24 months after the injections are administered.

In addition, our study revealed that a higher level of physical activity ameliorates the efficacy of epidural injections. Physical activity strengthens spinal muscles, relieves pressure on the spinal column, and enhances blood circulation. Patients who exercise regularly are physically fit, which relieves weight off their spine.

The findings of our study showed no correlation between BMI and the efficacy of epidural injections, which contrasts with a previous study that found better results with a lower BMI.7 Our study also found that, there was no correlation with the gender or age of the patient contrary to previous studies, where being female and young was associated with worse and better results, respectively.13

Our results also demonstrated that improvement after epidural injection was less in patients with a higher household crowding index, in contrast to another previous study.15 This finding could be explained by the fact that spinal stenosis worsens over time, which means that delayed treatment, due to financial issues, exacerbates physical disability due to more damage to the spinal cord and nerves. Severe cases can lead to bowel and bladder incontinence, as well as permanent paralysis.

Furthermore, there was a considerable number of patients (57.8%) in our study who were relieved with the injections without subsequent need for surgery in the near future; this finding suggests that epidural injections can replace the surgical approach in some patients, which would be beneficial especially for the elderly with comorbidities who cannot tolerate surgery.

Our study provides reliable results due to many reasons; first, the injections were performed by a highly trained anesthesiologist, which ensures that the medication is delivered to the affected area in a correct way, using a safe and tolerable dosage. Second, we are one of the few teams of researchers who have examined the effects of epidural injections over a long period of time. Third, the physician who performed the injections had no contact with the patients during the data collection, which was confidential and non-biased.

There are some limitations to this study. Retrospective fashioned studies are known to have recall bias because people provide information about past events. The sample used in our study does not represent the total population since it was withdrawn from one hospital (selection bias). Retrospective studies cannot prove causality. Finally, there may be any residual confounding bias since not all factors associated with pain were taken into consideration.

Conclusion

Epidural injections seem to be effective for the management of pain and functional disability in LSS. Physicians should encourage patients with LSS who do not improve with oral analgesics and lifestyle changes, to take epidural injections. Furthermore, they should encourage them to reduce sedentary time and engage in activities such as walking, swimming, and stretching. In patients who cannot tolerate surgery or refuse it, epidural injections can be considered as an alternative, along with lifestyle modification and physiotherapy. Doctors should inform their patients about the importance of treating spinal stenosis as soon as possible due to the high morbidity of untreated lumbar stenosis, and any financial issues should be properly addressed to provide the best quality care to patients. Future research is needed to better understand which patients with LSS could benefit more from epidural injections.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

| 1 |

Ivanov I, Milenković Z, Stefanović I, Babić M.

[Lumbar spinal stenosis.

Srp Arh Celok Lek. 1998;126(11-12):450-456.

|

| 2 |

Molina M, Wagner P, Campos M.

[Spinal lumbar stenosis: an update].

Rev Med Chil. 2011;139(11):1488-1495.

|

| 3 |

Daffner SD, Wang JC.

The pathophysiology and nonsurgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis.

Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:657-668.

|

| 4 |

Truumees E.

Spinal stenosis: pathophysiology, clinical and radiologic classification.

Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:287-302.

|

| 5 |

Yuan PS, Booth RE, Albert TJ.

Nonsurgical and surgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis.

Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:303-312.

|

| 6 |

Rosen CD, Kahanovitz N, Bernstein R, Viola K.

A retrospective analysis of the efficacy of epidural steroid injections.

Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(228):270-272.

|

| 7 |

Sabbaghan S, Mirzamohammadi E, Ameri Mahabadi M, et al.

Short-term efficacy of epidural injection of triamcinolone through translaminar approach for the treatment of lumbar canal stenosis.

Anesth Pain Med. 2020;10(1):e99764.

|

| 8 |

Barré L, Lutz GE, Southern D, Cooper G.

Fluoroscopically guided caudal epidural steroid injections for lumbar spinal stenosis: a restrospective evaluation of long term efficacy.

Pain Physician. 2004;7(2):187-193.

|

| 9 |

Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al.

Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):373-381.

|

| 10 |

Liu K, Liu P, Liu R, Wu X, Cai M, Xia K.

Steroid for epidural injection in spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:707-716.

|

| 11 |

Delport EG, Cucuzzella AR, Marley JK, Pruitt CM, Fisher JR.

Treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with epidural steroid injections: a retrospective outcome study.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(3):479-484.

|

| 12 |

Leung SM, Chau WW, Law SW, Fung KY.

Clinical value of transforaminal epidural steroid injection in lumbar radiculopathy.

Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21(5):394-400.

|

| 13 |

Cosgrove JL, Bertolet M, Chase SL, Cosgrove GK.

Epidural steroid injections in the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis efficacy and predictability of successful response.

Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(12):1050-1055.

|

| 14 |

Slater J, Kolber MJ, Schellhase KC, et al.

The influence of exercise on perceived pain and disability in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(2):136-147.

|

| 15 |

Jayabalan P, Bergman R, Huang K, Maas M, Welty L.

Relationship between socioeconomic status and the outcome of lumbar epidural steroid injections for lumbar radiculopathy.

Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;102(1):52-57.

|

| 16 |

Melki I, Beydoun H, Khogali M, Tamim H, Yunis K.

Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting.

J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):476-480.

|

| 17 |

Weary-Smith KA.

Validation of the Physical Activity Index (PAI) as a measure of total activity load and total kilocalorie expenditure during submaximal treadmill walking.

|