Abstract

Background

Postoperative pain after cesarean section (CS) can significantly impact patient recovery and morbidity if not managed effectively. This study compares the efficacy of two multimodal analgesic combinations—paracetamol with ibuprofen (PI) and paracetamol with ketorolac (PK)—in managing postoperative pain after CS, and assesses the incidence of side effects.

Methods

This single-blind clinical trial was conducted from June to July 2024 at Prof. Dr. W. Z. Johannes Hospital, Kupang, Indonesia, involving 60 patients undergoing elective CS under spinal anesthesia, randomly assigned into two groups. The PI group received 400 mg of intravenous ibuprofen post-delivery, followed by 1,000 mg of oral paracetamol and 400 mg of ibuprofen every 8 hours. The PK group was given 30 mg of intravenous ketorolac, followed by 1,000 mg of oral paracetamol and 30 mg of intravenous ketorolac every 8 hours. Pain was assessed using the numeric rating scale (NRS) at 8, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively, while opioid rescue use (NRS > 4) and side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain were also recorded.

Results

Pain scores were significantly lower in the PI group at 8 and 24 hours postoperatively (

Conclusion

PI may represent a more favorable option for early postoperative pain control and lower epigastric pain effect, pending further validation in larger, multicenter trials. Both combinations had similar outcomes in terms of opioid use and PONV.

Keywords

cesarean section, combination Paracetamol-Ibuprofen, combination Paracetamol-Ketorolac, postoperative pain

Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) is one of the most common surgical procedures performed globally, especially in cases where vaginal delivery is contraindicated due to maternal or fetal complications. The rate of cesarean deliveries has been increasing worldwide, driven by medical indications and patient preferences. 1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CSs account for 21% of all births globally, with this figure expected to rise to 29% by 2030. 3 In Indonesia, the prevalence of CS has risen significantly, from 4% in 2017 to 18.5% in 2021. Postoperative pain following CS is a major concern, as inadequate pain management can delay recovery, hinder mother-infant bonding, and negatively affect breastfeeding. 1 Effective post-surgical pain management is crucial in improving patient outcomes, especially in enhanced recovery protocols. 4,5

Multimodal analgesia, which involves using a combination of drugs with different mechanisms of action, is increasingly recommended for post-CS pain management. This approach helps to reduce the overall need for opioids, thus mitigating opioid-related side effects such as sedation, nausea, and gastrointestinal (GI) issues. 6 The combination of non-opioid analgesics, mainly paracetamol (or acetaminophen) with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), is one of the most reported multimodal approaches used in clinical practice. 7 A study from Shehab et al. 8 found that intravenous ibuprofen reduces postoperative pain after CS better than intravenous ketorolac. The visual analogue scale at rest and during movement is decreased, as is the 24-hour opioid requirement.

However, the comparative efficacy of different NSAID combinations with paracetamol, specifically paracetamol-ibuprofen versus paracetamol-ketorolac, remains under-researched in post-CS settings. This study aims to fill this gap by comparing the effectiveness of paracetamol combined with either ibuprofen or ketorolac in managing post-CS pain. Both regimens are hypothesized to provide adequate analgesia, but with potentially differing effects on pain control, opioid consumption, and the incidence of side effects such as nausea and epigastric pain. Understanding these differences is critical for optimizing pain management strategies and improving the quality of postoperative care for CS patients.

Methods

This study was designed as a single-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted over two months, from June to July 2024, at the Central Surgery Unit of Prof. Dr. W. Z. Johannes Regional Hospital, Kupang, Indonesia. The research focused on pregnant women undergoing elective CSs under spinal anesthesia. The study aimed to compare the efficacy of two analgesic combinations—paracetamol with ibuprofen (PI) and paracetamol with ketorolac (PK)—for postoperative pain management. Ethical approval was obtained from the local Ethics Committee of Universitas Nusa Cendana, and all participants provided informed consent before enrolment. This research was financed from PNBP funds from Universitas Nusa Cendana SP DIPA-023.17.2.677528/2024 with Activity Code 4471.DBA.004.051.B Account 525119 Financial Year 2024.

The study population consisted of women aged between 18 and 40 years who were classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status II and scheduled for elective CS under spinal anesthesia. Patients were excluded if they had contraindications to spinal anesthesia, a history of NSAID or opioid allergies, a history of asthma, or were already using opioids. In this study, 65 patients were recruited using consecutive sampling. However, 3 patients were excluded due to a history of NSAID allergy, and 2 others declined participation. Then, 60 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. These participants were randomly allocated into two treatment groups: the paracetamol–ibuprofen group (PI group) and the paracetamol–ketorolac group (PK group). Randomization was performed using an online simple random allocation tool to ensure equal distribution of patients into each group. Only the researcher knows which intervention is given according to the group allocation, but the patient does not know, ensuring a single-blind design.

Patients undergoing CS in both groups were given 1,000 mg of oral paracetamol 2 hours before surgery. Anesthesia was performed using spinal anesthesia with the local anesthetic bupivacaine 0.5% heavy 10 mg without adjuvant in a sitting position. The level of the sensory block is assessed using the pinprick test. The surgery may commence once the block height reaches T4–T6. Then, the group PI received 400 mg of intravenous ibuprofen immediately after the baby was delivered, followed by 1,000 mg of oral paracetamol and 400 mg of oral ibuprofen every 8 hours, starting 8 hours after surgery and continuing for two days. The group PK was administered 30 mg of intravenous ketorolac immediately after the baby was delivered, followed by 1,000 mg of oral paracetamol and 30 mg of intravenous ketorolac every 8 hours, also starting 8 hours postoperatively and continuing for two days. Pain levels were assessed using the numeric rating scale (NRS), a validated scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable), at 8, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively. Both resting and moving pain were measured to capture a comprehensive profile of postoperative pain. Additionally, the need for opioid rescue analgesia was monitored. Rescue analgesia morphine 2 mg intravenous bolus was administered by a blinded nurse if NRS > 4 at the first time during the 48-hour observation period. A repeat dose of 1 mg morphine is administered one hour after the previous dose until the NRS score is < 4. Subsequently, the total dose of morphine received within 48 hours was recorded.

Side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain, were also recorded within 48 hours postoperatively. These were self-reported by patients and confirmed by the attending clinical staff. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) severity was graded as: Grade 0 (no vomiting), Grade 1 (1–2 episodes/24 hours), Grade 2 (≥ 3 episodes or rescue antiemetics), Grade 3 (refractory vomiting). The study primarily aimed to compare pain scores between the two groups at the specified time intervals, while secondary outcomes included the total opioid consumption and incidence of side effects in both treatment arms. All data were collected by blinded research assistants and recorded in a pre-designed clinical data collection form.

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and baseline characteristics of the study participants. Continuous variables, such as age and pain scores, were reported as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables, such as the occurrence of side effects, were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The data distribution in this study was normal, so independent sample

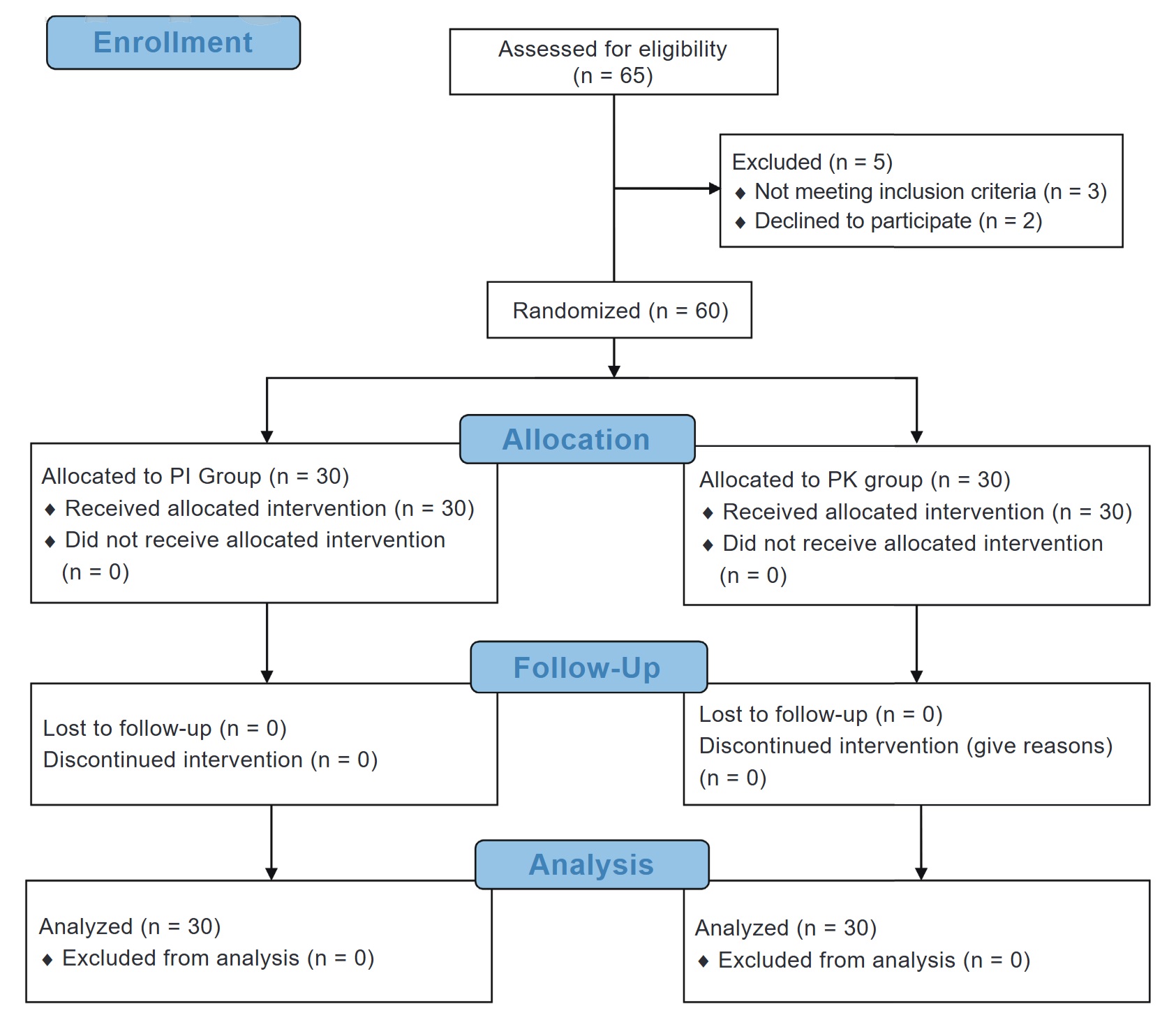

The sample size of 60 patients (30 in each group) was calculated to detect a significant difference in pain scores between the two groups, with a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%, based on prior studies of postoperative analgesia following CS. These studies suggested that a minimum of 25 patients per group would be sufficient to detect clinically meaningful differences in pain outcomes. To account for potential dropouts or protocol violations, we aimed to recruit 60 patients in total. All patients completed the study, and there were no dropouts after randomization (Figure 1).

Download full-size image

Abbreviations: PI, paracetamol with ibuprofen; PK, paracetamol with ketorolac.

This study adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, ensuring rigorous reporting of trial procedures and outcomes. The randomization process, blinding, and statistical methods were carefully chosen to minimize bias and ensure the reliability of the results. By comparing two widely used NSAID combinations, this trial aimed to provide evidence to optimize postoperative pain management in CS patients while minimizing opioid use and related complications.

Results

The final analysis included 60 participants in total who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Based on variables such as age, body mass index (BMI), duration of surgery, parity, history of previous CS, pain scores during rest and movement at 8, 24, and 48 hours after surgery, the need for rescue opioids, and the incidence of side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain, the two groups—the PI group and the PK group—were compared. Table 1 presents the findings and provides a thorough comparison of these characteristics between the two groups.

|

Variable |

Group PI |

Group PK |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (years), mean ± SD |

29.7 ± 6.4 |

30.0 ± 6.9 |

0.862 a |

|

BMI (kg/m 2 ), mean ± SD |

25.34 ± 1.00 |

25.60 ± 0.80 |

0.479 a |

|

Duration of surgery (minutes), mean ± SD |

58.77 ± 5.40 |

57.47 ± 5.40 |

0.944 a |

|

Parity |

0.592 b |

||

|

Primigravida |

10 |

12 |

|

|

Multigravida |

20 |

18 |

|

|

Cesarean section history |

0.417 b |

||

|

Yes |

12 |

9 |

|

|

No |

18 |

21 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PI, paracetamol with ibuprofen; PK, paracetamol with ketorolac; SD, standard deviation.

aIndependent t-test.

bChi-square.

The comparison of demographic characteristics such as age, BMI, duration of surgery, parity, history of previous CS between groups showed no statistically significant difference (

|

Variable |

Group PI |

Group PK |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pain score at rest, mean ± SD |

|||

|

8th hour |

2.3 ± 1.8 |

3.4 ± 1.6 |

0.009 a |

|

24th hour |

1.4 ± 1.3 |

2.2 ± 1.4 |

0.024 a |

|

48th hour |

0.5 ± 0.6 |

0.7 ± 0.6 |

0.094 a |

|

Pain score on movement, mean ± SD |

|||

|

8th hour |

4.9 ± 1.3 |

5.7 ± 1.3 |

0.031 a |

|

24th hour |

3.6 ± 1.3 |

4.3 ± 1.0 |

0.020 a |

|

48th hour |

2.4 ± 0.7 |

2.4 ± 0.6 |

1.000 a |

Abbreviations: PI, paracetamol with ibuprofen; pk, paracetamol with ketorolac; SD, standard deviation.

aIndependent

In terms of pain scores during movement, the PI group reported significantly lower pain levels than the PK group at both 8 and 24 hours postoperatively (

A significant difference was observed in mean resting and movement pain scores at 8, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively in the PI group (all

|

Variable |

Mean ± SD |

CI 95% |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pain score at rest |

|||

|

8th hour |

2.30 ± 0.32 |

1.61–2.92 |

< 0.001 a |

|

24th hour |

1.40 ± 0.23 |

0.92–1.88 |

|

|

48th hour |

0.50 ± 0.10 |

0.65–0.68 |

|

|

Pain score on movement |

|||

|

8th hour |

4.90 ± 0.25 |

4.42–5.44 |

< 0.001 a |

|

24th hour |

3.60 ± 0.24 |

3.07–4.06 |

|

|

48th hour |

2.40 ± 0.12 |

2.18–2.69 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PI, paracetamol with ibuprofen; SD, standard deviation.

aRepeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) test.

|

Variable |

Mean ± SD |

CI 95% |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pain score at rest |

|||

|

8th hour |

3.40 ± 0.29 |

2.84–4.02 |

< 0.001 a |

|

24th hour |

2.20 ± 0.26 |

1.68–2.72 |

|

|

48th hour |

0.73 ± 0.12 |

0.49–0.97 |

|

|

Pain score on movement |

|||

|

8th hour |

5.70 ± 0.24 |

5.21–6.19 |

< 0.001 a |

|

24th hour |

4.30 ± 0.18 |

3.92–4.68 |

|

|

48th hour |

2.40 ± 0.10 |

2.22–2.64 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PK, paracetamol with ketorolac; SD, standard deviation.

aRepeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) test.

Regarding the need for opioid rescue, 12 participants in the PI group and 17 in the PK group required additional opioid analgesia (2.33

±

0.65 mg vs. 2.47

±

0.62 mg) though this difference was not statistically significant (

|

Variable |

Group PI |

Group PK |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total morphine rescue (mg), mean ± SD |

2.33 ± 0.65 (n = 12) |

2.47 ± 0.62 (n = 17) |

0.656 a |

|

PONV, n (%) |

0.095 b |

||

|

Grade 0 |

27 (90.0) |

22 (73.3) |

|

|

Grade 1 |

3 (10.0) |

8 (26.7) |

|

|

Epigrastric pain, n (%) |

0.038 b |

||

|

Yes |

2 (6.7) |

8 (26.7) |

|

|

No |

28 (93.3) |

22 (73.3) |

Abbreviations: PI, paracetamol with ibuprofen; PK, paracetamol with ketorolac; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; SD, standard deviation. a Independent t-test. b Chi-square test.

aIndependent t-test.

bChi-square test.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the efficacy and safety of two commonly used analgesic regimens PI and PK in managing postoperative pain following CS. The concurrent administration of acetaminophen and NSAIDs has been shown to be more efficacious than either agent alone, and therefore, their combined use is recommended for post-CS analgesia in patients without contraindications. However, staggered dosing regimens for around-the-clock administration of these medications may result in increased patient interruptions and nursing workload without discernible benefits. Consequently, consideration should be given to co-administering these agents at fixed intervals (e.g., every 6 hours) to optimize analgesic efficacy and minimize disruptions to patient care.

9

Intravenous ketorolac and oral ibuprofen are the most commonly employed NSAIDs currently in the United States, although other options such as naproxen and diclofenac are viable alternatives and have been investigated extensively in obstetric and non-obstetric patient populations.

10

Both regimens are frequently employed in clinical settings, but their relative effectiveness in terms of pain control, opioid rescue requirements, and associated side effects has remained underexplored. The results in this study indicate that the PI regimen offers superior pain relief in the early postoperative period (within the first 24 hours) compared to the PK regimen, as evidenced by the significantly lower pain scores both at rest and during movement at 8 and 24 hours. These results are also consistent with the findings from Abdelbaser et al.

11

study, where the administration of intravenous ibuprofen postoperatively led to significantly lower pain scores compared to intravenous ketorolac administration. Bharat’s study also revealed that postoperative pain scores were significantly lower

in the ibuprofen group. Furthermore, the time to first rescue analgesia and the total number of rescue analgesics required were also reduced in the ibuprofen group.

12

However, by 48 hours postoperatively, the pain scores in both groups had levelled off, suggesting that the analgesic efficacy of both regimens becomes comparable over time.

13

Ibuprofen exhibits a faster onset time compared to ketorolac, especially when administered intravenously. In one study, the analgesic onset time for intravenous ibuprofen was approximately 10 to 15 minutes, with significant pain reduction observed after this period.

14,15

In contrast, intravenously administered ketorolac typically requires a longer duration to achieve optimal analgesic effects, with an onset ranging between 30 and 60 minutes.

16

These pharmacological properties may explain why the combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen is more effective in reducing pain scores during the early postoperative period compared to the combination of paracetamol and ketorolac.

These findings are consistent with previous research highlighting the synergistic effects of paracetamol and ibuprofen in managing postoperative pain. Ibuprofen, an NSAID, works by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are responsible for producing prostaglandins that mediate inflammation and pain. When combined with paracetamol, which acts primarily in the central nervous system, the result is a broader and more effective pain relief mechanism. 17 The lower pain scores at 8 and 24 hours in the PI group suggest that this combination is particularly effective during the immediate postoperative period when pain intensity is typically highest. In contrast, ketorolac, another NSAID used in the PK regimen, has a similar COX inhibition mechanism, but its analgesic effect may not be as potent or prolonged as the ibuprofen combination when paired with paracetamol. 13

At 48 hours postoperatively, there was no significant difference in pain scores at rest and during movement between the PI and PK groups. These findings are consistent with the study by Amin et al. 16 , which observed no difference in postoperative pain scores at rest and during movement following laparotomy hysterectomy between the group receiving intravenous ibuprofen and the group receiving intravenous ketorolac in the preoperative period. Interesting findings in this study are the diminishing difference in pain scores between the two regimens at 48 hours postoperatively. By this time, pain levels had decreased substantially in both groups, and the differences were no longer statistically significant. This suggests that while the PI combination may offer superior pain control early on, both regimens provide adequate analgesia for the longer-term management of postoperative pain. This aligns with the natural trajectory of postoperative pain, which tends to peak within the first 24 hours and gradually diminish thereafter. As a result, the choice between these two analgesic regimens may be more critical in the immediate postoperative period, while either regimen may be acceptable for ongoing pain management beyond 24 hours. These findings align with the study by Amin et al. 16 , which reported no difference in postoperative pain scores at rest and during movement following laparotomy hysterectomy between the group receiving intravenous ibuprofen and the group receiving intravenous ketorolac in the preoperative period.

The need for rescue opioids in this study was not significantly different between the two groups, indicating that both regimens provide comparable levels of pain control in terms of preventing the need for additional opioid analgesia. This is a key finding, as the reduction of opioid use in postoperative settings is a major goal in modern pain management strategies due to the well-known risks associated with opioid use, including dependency, tolerance, and adverse side effects. The fact that both regimens limited the need for opioid rescue to a similar extent suggests that they are both viable options in the effort to minimize opioid consumption in postoperative care. 18,19 However, it is worth noting that the slightly higher opioid use in the PK group, though not statistically significant, may point to a marginally less effective pain control mechanism during the critical early postoperative hours. A study by Poljak and Chappelle 20 found that regular administration of a combination of ibuprofen and paracetamol every 4 hours resulted in a significant reduction in pain scores and opioid requirements compared to on-demand administration alone following post-CS surgery.

In terms of side effects, the study found no significant difference between the two regimens with regard to nausea and vomiting. While there were numerically more cases of these side effects in the PK group, the lack of statistical significance suggests that both regimens are generally well-tolerated. This finding is consistent with the results of Gaus et al.

4

, which demonstrated that there were no significant differences in adverse effects between ibuprofen and ketorolac for post-CS pain management. However, in this study, the incidence of epigastric pain was significantly lower in the PI group compared to the PK group (

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that PI provides superior pain relief compared to PK during the early postoperative period following CS. PI may represent a more favorable option for early postoperative pain control, pending further validation in larger, multicenter trials. Pain scores, both at rest and during movement, were significantly lower in the PI group at 8 and 24 hours postoperatively, though the difference diminished by 48 hours, indicating that both regimens offer comparable long-term analgesia. The need for rescue opioids and the incidence of side effects such as nausea and vomiting were not significantly different between the two groups, suggesting that both analgesic combinations are generally well-tolerated. Nevertheless, the PI combination demonstrated a lower incidence of epigastric pain as an adverse effect compared to the PK combination. Given the enhanced pain control observed with the PI combination in the crucial early postoperative hours and its favorable safety profile, this regimen may be recommended as the preferred option for postoperative pain management in CS patients. However, further studies with larger populations and extended follow-up are necessary to substantiate these findings and explore the long-term safety and efficacy of these analgesic strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the director and operating room staff of Prof. Dr. W. Z. Johannes Regional General Hospital Kupang, who have allowed this research to be carried out in this hospital.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

| 1 |

Wyatt S, Silitonga PII, Febriani E, Long Q.

Socioeconomic, geographic and health system factors associated with rising C-section rate in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study using the Indonesian demographic and health surveys from 1998 to 2017.

BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e045592.

|

| 2 |

Cheng J, Wan M, Yu X, et al.

Pharmacologic analgesia for cesarean section: an update in 2024.

Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2024;28(10):985-998.

|

| 3 |

Angolile CM, Max BL, Mushemba J, Mashauri HL.

Global increased cesarean section rates and public health implications: a call to action.

Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(5):e1274.

|

| 4 |

Gaus S, Afif Y, Ala AA, Tanra AH, Ratnawati R, Rum M.

Comparison of pain control and inflammatory profile in cesarean section patients treated with multimodal analgesia utilizing paracetamol and ibuprofen.

|

| 5 | |

| 6 |

Saucillo-Osuna J, Wilson-Manríquez EA, López-Hernández MN, Garduño-López A.

Perioperative analgesia in caesarean section: what’s new?

|

| 7 |

Silva F, Costa G, Veiga F, Cardoso C, Paiva-Santos AC.

Parenteral Ready-to-Use Fixed-Dose Combinations Including NSAIDs with Paracetamol or Metamizole for Multimodal Analgesia-Approved Products and Challenges.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(8):1084.

|

| 8 |

Shehab AS, Bochra KA, Tawfik TA.

The effectiveness of intravenous ibuprofen versus intravenous ketorolac for postoperative pain relief after caesarean section.

Research and Opinion in Anesthesia & Intensive Care. 2024;11(1):25-30.

|

| 9 |

Sutton CD, Carvalho B.

Optimal pain management after cesarean delivery.

Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(1):107-124.

|

| 10 |

Reed SE, Tan HS, Fuller ME, et al.

Analgesia after cesarean delivery in the United States 2008-2018: a retrospective cohort study.

Anesth Analg. 2021;133(6):1550-1558.

|

| 11 |

Abdelbaser I, Mageed NA, El-Emam ESM, ALseoudy MM.

Comparison of intravenous ibuprofen versus ketorolac for postoperative analgesia in children undergoing lower abdominal surgery: a randomized, controlled, non-inferiority study.

Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed). 2022;69(8):463-471.

|

| 12 |

Bharat G, Neelima T, Sarma AA, Rowthu U, Rao K.

Comparison of ketorolac versus ibuprofen for postoperative pain management in total abdominal hystrectomy surgeries.

IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2024;23(9):7-12.

|

| 13 |

Uribe AA, Arbona FL, Flanigan DC, Kaeding CC, Palettas M, Bergese SD.

Comparing the efficacy of IV ibuprofen and ketorolac in the management of postoperative pain following arthroscopic knee surgery.

Front Surg. 2018;5:59.

|

| 14 |

Forouzanfar MM, Mohammadi K, Hashemi B, Safari S.

Comparison of intravenous ibuprofen with intravenous ketorolac in renal colic pain management; a clinical trial.

Anesth Pain Med. 2019;9(1):e86963.

|

| 15 |

Zhou P, Chen L, Wang E, He L, Tian S, Zhai S.

Intravenous ibuprofen in postoperative pain and fever management in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2023;11(4):e01123.

|

| 16 |

Amin S, Hasanin A, Attia OA, et al.

Intravenous ibuprofen versus ketorolac for perioperative pain control in open abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial.

BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24(1):202.

|

| 17 |

Atkinson HC, Currie J, Moodie J, et al.

Combination paracetamol and ibuprofen for pain relief after oral surgery: a dose ranging study.

Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(5):579-587.

|

| 18 |

Dwarica DS, Pickett SD, Zhao YD, Nihira MA, Quiroz LH.

Comparing ketorolac with ibuprofen for postoperative pain: a randomized clinical trial.

Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26(4):233-238.

|

| 19 |

Hadley EE, Monsivais L, Pacheco L, et al.

Multimodal pain management for cesarean delivery: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial.

Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(11):1097-1105.

|

| 20 |

Poljak D, Chappelle J.

The effect of a scheduled regimen of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on opioid use following cesarean delivery.

J Perinat Med. 2020;48(2):153-156.

|

| 21 |

Lee GG, Park JS, Kim HS, Yoon DS, Lim JH.

Clinical effect of preoperative intravenous non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on relief of postoperative pain in patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: intravenous ibuprofen vs.

Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2022;26(3):251-256.

|