Abstract

Background

Successful placement of an endotracheal tube (ETT) and its timely confirmation in obese patients is of utmost importance. Chest auscultation might be misleading in the obese. Considering the need for an additional efficient method, the present study compared tracheal and pleural ultrasonography (USG) for confirming ETT placement in overweight and obese patients.

Methods

A prospective, comparative, randomized, single-blinded study enrolled a total of 64 overweight, obese class I and class II patients aged between 18 and 60 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists g rade s I or II, scheduled for elective surgeries under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Patients were randomized into two groups of 32 each based on the USG technique used for confirmation of ETT placement. Group T is Tracheal USG, and Group P is Pleural USG. The primary outcome was a comparison of the time required by tracheal and pleural ultrasonography techniques for confirmation of ETT placement, while the secondary outcome was a comparison of the time required by both USG techniques with the time for auscultation and capnographic confirmation of ETT placement.

Results

Tracheal USG took the least time (4.19 ± 0.89

seconds

) compared to pleural USG (10.88 ± 1.16

seconds

) and proved to be faster. Time taken for auscultation (

Conclusion

Tracheal USG provides a faster confirmation of endotracheal intubation than pleural USG in overweight and obese patients. Pleural USG has the added advantage of diagnosing endobronchial intubation.

Keywords

auscultation, capnography, intubation, obese, ultrasonography

Introduction

Confirmation of endotracheal tube (ETT) placement and its correct positioning, especially for obese patients, might be a challenging task even for experienced anesthesiologists. Most of the obese patients have a difficult airway and are prone to rapid desaturation. Delayed recognition of oesophageal or endobronchial intubation can be fatal in them. Therefore, it is crucial to secure and confirm the position of ETT as quickly as possible. 1 Auscultatory confirmation of the tracheal tube may be unreliable or misleading because of increased chest wall thickness in obesity. Capnography, though the gold standard for ETT confirmation, has its own limitations, and its accuracy may be compromised in conditions like cardiac arrest or severe bronchospasm. 2-4 Thus, any single method for ETT confirmation may not be sufficient in these patients.

Ultrasonography (USG), being a non-invasive, portable, and real-time diagnostic tool, has a novel role in airway management, including confirmation of ETT placement. It provides rapid and accurate results as unaffected by low pulmonary blood flow. 5-7 USG can visualize lung expansion by motion of the diaphragm and pleura. 8 Three USG techniques, namely tracheal USG, lung sliding sign by pleural USG, and bilateral diaphragmatic dome movement, are used for ETT confirmation. 5,9 The tracheal USG can detect oesophageal intubation prior to starting ventilation, thus preventing unnecessary gastric insufflation, while the sliding lung sign and diaphragmatic movement can identify endobronchial intubation by assessing pleural and diaphragm movements, respectively, helping to avoid errors that may be overlooked by traditional methods.

Many studies have proven the feasibility and accuracy of USG in confirmation of ETT placement. Men and Yan 10 found tracheal USG highly sensitive and specific in confirming ETT in obese patients, while Rajan et al. 11 found lung sliding more accurate and rapid for confirming ETT in obese patients. But very few studies have compared two USG techniques in terms of the time required for confirming ETT placement in the overweight and obese population. Thus, the present study was conducted with the primary outcome of comparison of the time required by tracheal and pleural USG for confirmation of ETT placement, while the secondary outcome was comparison of the time required by both USG techniques with the time for auscultation and capnographic confirmation of ETT placement. We hypothesized that USG would be faster in confirming ETT placement in obesity.

Methods

After obtaining Institutional Ethics Committee (BVDUMC/IEC/93) approval and CTRI registration (CTRI/2023/09/057545) present prospective, comparative, randomized, single blinded study was conducted from June 2022 to January 2024. A total 64 overweight (body mass index [BMI]: 25.0–29.9), obese class I (BMI: 30.0–34.9), and class II (BMI: 35.0–39.9) patients aged between 18 to 60 years, of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades I or II scheduled for elective surgeries under general anesthesia (GA) with endotracheal intubation were enrolled in the study. Patients not willing to participate, with mouth opening of less than two fingers, cervical spine disorders, abnormal airway anatomy, and a history of neck surgery, or radiation or any lung pathology were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained, and the study was done in accordance with the most recent version of the Helsinki declaration. A detailed preanesthesia check-up was done the day prior to surgery.

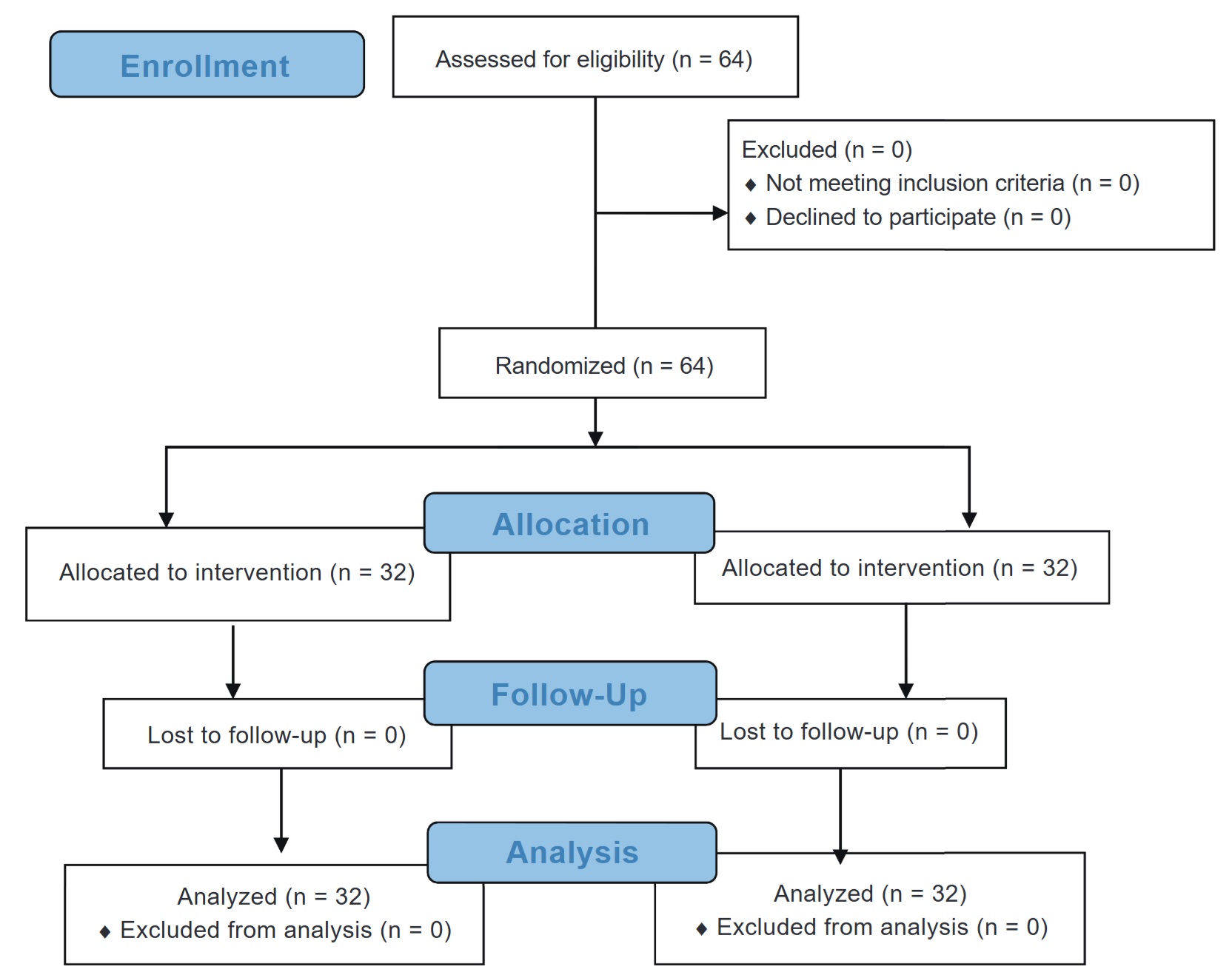

Sample size was calculated from the SD of the previous study done by Amin et al. 12 keeping confidence interval (CI) at 95% and power at 80%, a sample was calculated to be 64. Patients were randomized by computer generated randomization into either of the two groups with 32 patients in each based-on USG technique used for confirmation of ETT placement.

(1) Group T: Tracheal ultrasound

(2) Group P: Pleural ultrasound

Allocation concealment was done by placing the groups in sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes using the SNOSE method. In the preoperative room, USG scanning and skin markings were performed for better visualization of the trachea and visceral parietal pleural interface (Figures 1 and 2). Upon arrival in the operating theater, standard monitoring as an electrocardiogram, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and capnography, was initiated. Baseline vitals were recorded. The intravenous injection line was secured patients were placed in Rapid Airway Management Position (RAMP) for laryngoscopy and intubation. Standard GA protocol was followed. All intubations were performed by senior anesthesia residents.

Immediately after intubation, ETT placement confirmation was done with chest auscultation, capnography in all patients as well as by USG according to assigned group, either the tracheal USG or the pleural USG. The Sonosite EDGE II ultrasound machine with a linear transducer probe (9–13 MHz) was used for imaging. USG scanning was done by senior anesthesiologists. All scans were performed by the same anesthesiologists, and that faculty also noted the time for ETT confirmation by USG.

The time for confirmation of the correct placement of ETT was recorded for USG, capnography, and chest auscultation. All patients were blinded to the group allocation.

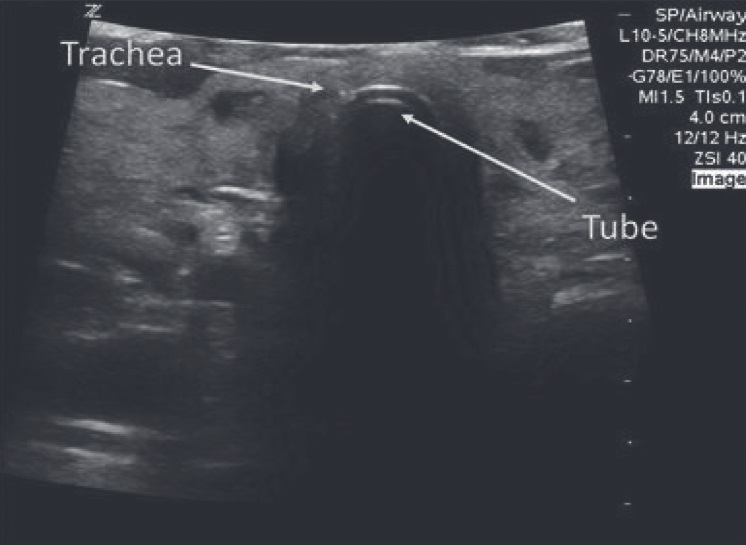

In Group T

(1) Probe placement: On the anterior aspect of the neck, just above the suprasternal notch in the transverse plane (depth 2.5 cm) as seen in Figure 1

Download full-size image

(2) ETT placement confirmation: By USG image of “comet tail” sign and posterior shadowing with a single air mucosal interface, while a double tract sign indicated oesophageal intubation as seen in USG (Figure 3)

Download full-size image

(3) Time for ETT confirmation: Recorded from the placement of the probe till visualization of the comet tail sign

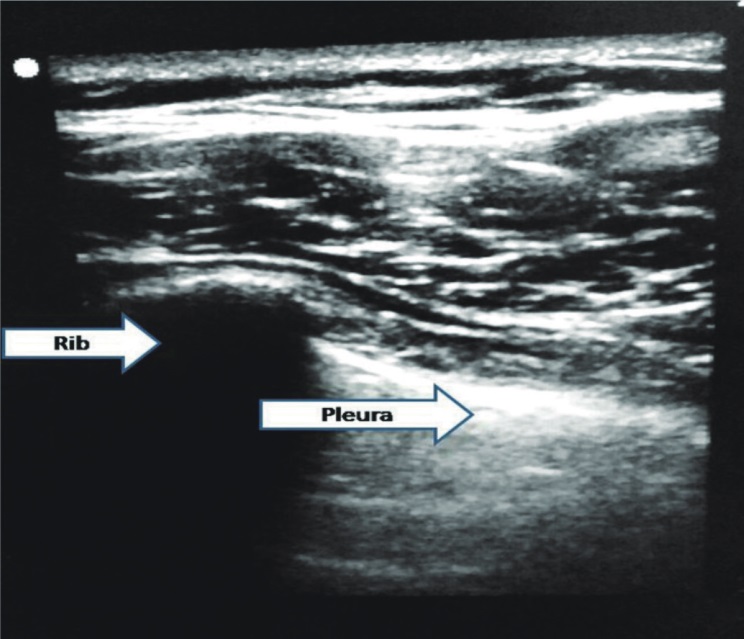

In Group P

(1) Probe placement: Vertically at the second or third intercostal space in the sagittal plane at the midclavicular line (depth 4.7 cm) (Figure 2)

Download full-size image

(2) ETT placement confirmation: By the bilateral lung sliding sign as shown in USG (Figure 4)

Download full-size image

(3) Time for ETT confirmation: Recorded from probe placement on the chest till completion of bilateral lung sliding

Chest auscultation time was recorded from the placement of the stethoscope till bilateral confirmation of air entry by standard five-point auscultation. The anesthesiologists who did the chest auscultation noted the time required for the same. For capnographic confirmation of tracheal intubation time was recorded from attachment of the breathing circuit till appearance of the 6th capnographic waveform by side-stream capnography. The senior anesthesia residents who intubated the patient and managed the ventilation recorded the time taken for capnographic confirmation.

Patients with unanticipated difficult intubations or desaturation below 90% were excluded from analysis. The remaining anesthesia management followed standard protocol. Oesophageal or endobronchial intubations, if any, were also noted.

Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data were presented as n (%), while continuous variables with normal distribution were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Inter-group comparisons of categorical variables were tested using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test if more than 20% of cells had an expected frequency < 5. The comparisons of the means of normally distributed continuous variables were performed using an independent sample

Results

A total of 64 patients (32 patients in each group) were analyzed (Figure 5). Demographic characteristics, including BMI and ASA grading of all patients, were comparable, as shown in Table 1. Also, there was no significant statistical difference in Mallampati grades and neck circumference of patients between the two groups.

Download full-size image

|

Parameter |

Tracheal USG (n = 32) |

Pleural USG (n = 32) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, years, mean ± SD |

41.69 ± 11.65 |

42.25 ± 11.19 |

0.845 |

|

Gender |

0.999 |

||

|

Male (%) |

14 (43.8) |

14 (43.8) |

|

|

Female (%) |

18 (56.2) |

18 (56.2) |

|

|

BMI, kg/m 2 , mean ± SD |

31.53 ± 3.32 |

32.59 ± 3.11 |

0.191 |

|

BMI category, kg/m 2 |

0.538 |

||

|

Overweight |

11 (34.4) |

7 (21.9) |

|

|

Class I obesity |

15 (46.9) |

18 (56.2) |

|

|

Class II obesity |

6 (18.7) |

7 (21.9) |

|

|

ASA |

0.802 |

||

|

Grade I |

16 (50.0) |

17 (53.1) |

|

|

Grade II |

16 (50.0) |

15 (46.9) |

|

|

MP |

0.134 |

||

|

Grade I |

8 (25.0) |

7 (21.9) |

|

|

Grade II |

23 (71.9) |

19 (59.4) |

|

|

Grade III |

1 (3.1) |

6 (18.7) |

|

|

Neck circumference, cm, |

|||

|

mean ± SD |

36.09 ± 4.47 |

38.19 ± 5.26 |

0.091 |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; MP, Mallampati; SD, standard deviation; USG, ultrasonography.

aData is presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

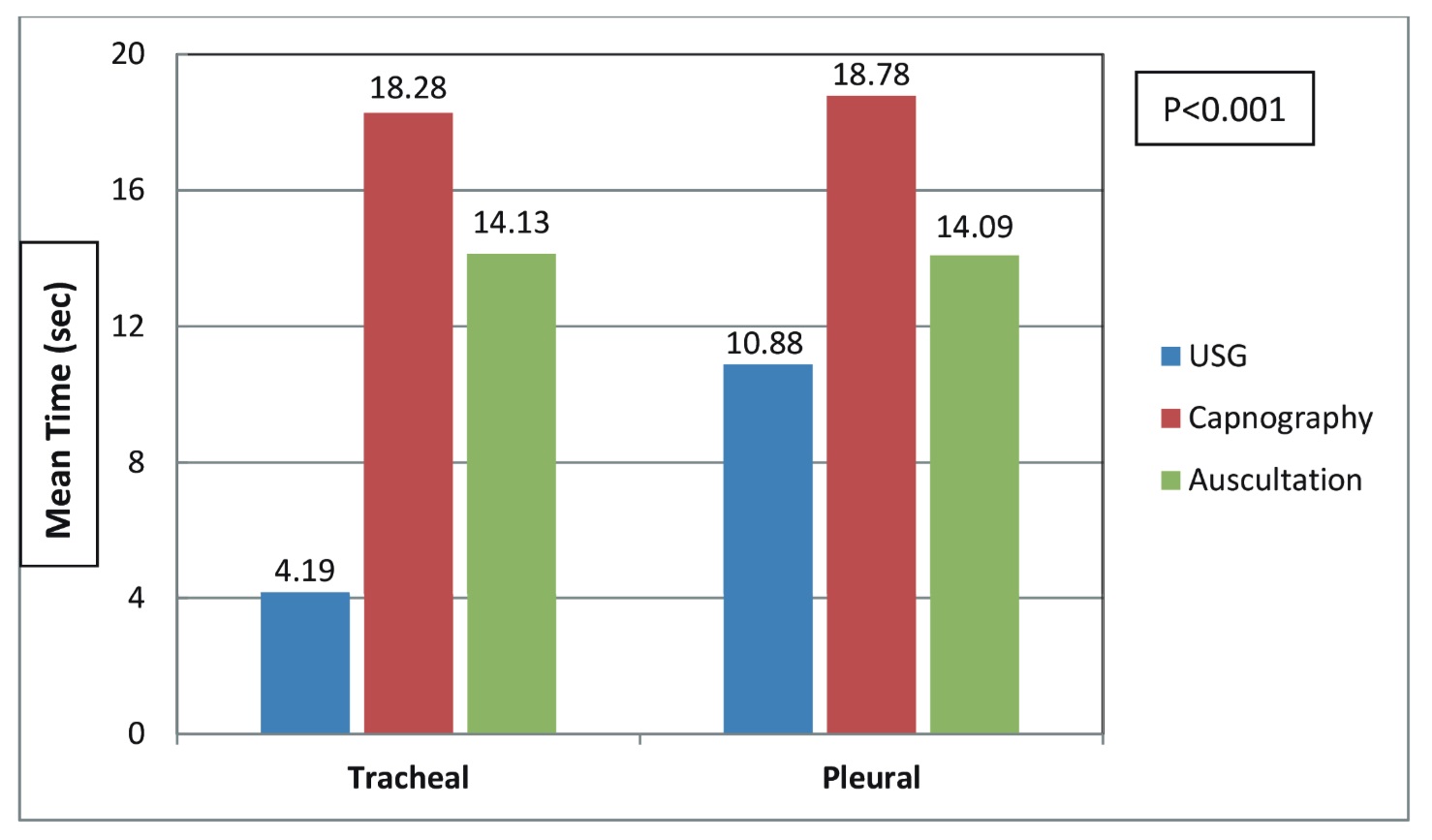

In the current study, on intergroup comparison as shown in Figure 6, tracheal USG was found to be faster as compared to pleural USG. The mean time for ETT confirmation with tracheal USG was 4.19 ± 0.89 seconds, while bilateral lung sliding was completed within 10.88 ± 1.16 seconds (

On intragroup comparison as seen in Figure 6, in the tracheal group, the mean confirmation time of USG was significantly shorter than both the mean time for capnography and auscultation, respectively (4.19 seconds vs. 18.28 seconds and 14.13 seconds,

Download full-size image

None of the study participants had esophageal intubation. In the tracheal group, 1 patient (3.1%) had right endobronchial intubation, and in the pleural group, 2 patients (6.3%) had endobronchial placement of ETT.

Discussion

Obesity is becoming a worldwide health problem. We are facing many overweight and obese patients for anesthesia. Successful tracheal intubation, its verification, along with maintaining oxygenation in these populations, can be a tight rope walk for anesthesiologists owing to an anticipated difficult airway and low functional residual capacity. Auscultatory confirmation might take time due to excess fat and may be doubtful. In this study, we compared two USG methods with respect to the time required for confirmation of ETT placement in overweight and obese patients.

The current study showed that tracheal USG was faster than pleural lung sliding in confirming ETT placement in obese patients, which was our primary outcome. The study conducted by Sethi et al. 5 compared the time taken by three different USG techniques to confirm ETT placement. In their study, tracheal USG was the fastest, with an average confirmation time of 3.8 seconds, while pleural and diaphragmatic scanning required 12.1 seconds and 13.8 seconds, respectively. This suggests that tracheal USG offers a more rapid method of confirming ETT placement. Research published by Thomas et al. 9 on 100 patients who needed emergency intubation, the mean time taken by tracheal USG was 8.27 ± 1.54 seconds to identify ETT position. Studies done by Amin et al. 12 , Muslu et al. 13 , and Chou et al. 14 also found tracheal USG faster. Pfeiffer et al. 15 primarily compared transthoracic ultrasound using lung sliding to auscultation alone in 24 obese patients in terms of time difference to confirm ETT position and found no significant difference in confirmation times between ultrasound and auscultation; however, ultrasound was faster (median time of 43 seconds) when compared with combination of auscultation and capnography (median time of 55 seconds).

In obese patients, obtaining good-quality USG images can be challenging due to positioning difficulties and excess subcutaneous fat, which increases the travel distance of the USG beam. We placed all patients in the RAMP position for laryngoscopy and intubation, which is preferred in obese patients, which might have enhanced the visualization of the upper airway as well as pleura, and explains the shorter time required for both USG methods compared to auscultation. We also did preprocedural scanning in the preoperative room as suggested by Pfeiffer et al. 15 and Sethi et al. 5 in their studies to decide the optimum probe position.

Though tracheal USG proved to be faster, it has its own limitation that it confirms tracheal versus oesophageal ETT placement only, but it can’t detect endobronchial placement of ETT. Right-sided endobronchial intubation could be quite possible in the obese population due to a short neck. Absence of lung sliding on one side by pleural USG aids in identifying endobronchial positioning. Rajan et al.

11

reported that their research on overweight and obese patients showed pleural USG by bilateral lung sliding was rapid (8.61 seconds) while conventional auscultation required (14.35 seconds) (

The longer time required for auscultatory confirmation in both groups of the present study may be attributed to the thick chest wall, and auscultation was performed at five standard points. In contrast, tracheal ultrasound involved scanning only one site over the anterior neck, while in the pleural group, lung sliding was visualized at two positions only. This could be the reason that auscultatory confirmation took a longer time as compared to both ultrasound techniques.

Chowdhury et al. 16 conducted the study in novice anesthesia residents with real-time USG. The study proved USG confirmation was fastest (36.50 ± 15.14 seconds) in comparison with chest auscultation (50.29 ± 15.50 seconds) and capnography 6th waveform. The author finally suggested the usefulness of real-time USG in guiding the junior residents during intubation itself. Herein, they measured time from the removal of the face mask till the confirmation by respective methods. While in our study, we specified the timeliness for confirmation by each method.

Though in this study all USG scans were performed by experienced anesthesiologists to maintain consistency and minimize variability, we suggest introducing airway ultrasound for novice and trainee anesthesia residents from the beginning, especially while managing specific populations as the obese.

Capnographic confirmation of ETT in our study took the maximum time. This could be because of the side-stream capnogram, and we measured the time till the complete appearance of 6 uniform square waveforms on the capnograph as confirmation of ETT placement. Kuppusamy et al. 17 study also showed more time for capnography (15.90 ± 13.14 seconds) when compared to USG (11.85 ± 2.32 seconds). However, the study conducted by Abhishek et al. 18 found faster confirmation times with both USG and capnography, though capnography was about 3 seconds quicker.

There were no incidences of oesophageal intubation in any of the two groups. However, in the tracheal group, one patient had right endobronchial intubation, which was detected by auscultation, while two patients in the pleural group had endobronchial placement of ETT, and that was verified by absent lung sliding on the left side. Herein, the pleural USG additionally helped in identifying too deeply inserted ETT.

However, the study has certain limitations. Morbid and super obese patients were not included in the study, limiting its generalizability, so further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of ultrasound in these populations. Future studies should assess the role of swellings, significant tracheal deviations, and distorted airway anatomy. As outcome assessors were not blinded to each other, and the study was single-blinded, it introduces potential bias. Additionally, ultrasound requires specialized expertise and skills, particularly when used in obese patients, as highlighted in the current study.

Conclusion

Tracheal USG provides rapid confirmation of endotracheal intubation than pleural USG in overweight and obese patients. Pleural USG has the extra advantage of detecting endobronchial intubation. Faster confirmation with tracheal USG, with the additional benefit of pleural USG for confirming endobronchial placement, proved promising, especially for overweight and obese patients.

References

| 1 |

Liew WJ, Negar A, Singh PA.

Airway management in patients suffering from morbid obesity.

Saudi J Anaesth. 2022;16(3):314-321.

|

| 2 |

Grmec S.

Comparison of three different methods to confirm tracheal tube placement in emergency intubation.

Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):701-704.

|

| 3 |

Takeda T, Tanigawa K, Tanaka H, Hayashi Y, Goto E, Tanaka K.

The assessment of three methods to verify tracheal tube placement in the emergency setting.

Resuscitation. 2003;56(2):153-157.

|

| 4 |

Li J.

Capnography alone is imperfect for endotracheal tube placement confirmation during emergency intubation.

J Emerg Med. 2001;20(3):223-229.

|

| 5 |

Sethi AK, Salhotra R, Chandra M, Mohta M, Bhatt S, Kayina CA.

Confirmation of placement of endotracheal tube—a comparative observational pilot study of three ultrasound methods.

J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(3):353-358.

|

| 6 |

Chou HC, Chong KM, Sim SS, et al.

Real-time tracheal ultrasonography for confirmation of endotracheal tube placement during cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Resuscitation. 2013;84(12):1708-1712.

|

| 7 |

Weaver B, Lyon M, Blaivas M.

Confirmation of endotracheal tube placement after intubation using the ultrasound sliding lung sign.

Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):239-244.

|

| 8 |

Kundra P, Mishra SK, Ramesh A.

Ultrasound of the airway.

Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55(5):456-462.

|

| 9 |

Thomas VK, Paul C, Rajeev PC, Palatty BU.

Reliability of ultrasonography in confirming endotracheal tube placement in an emergency setting.

Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21(5):257-261.

|

| 10 |

Men XQ, Yan XX.

Tracheal ultrasound for the accurate confirmation of the endotracheal tube position in obese patients.

J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(3):509-513.

|

| 11 |

Rajan S, Surendran J, Paul J, Kumar L.

Rapidity and efficacy of ultrasonographic sliding lung sign and auscultation in confirming endotracheal intubation in overweight and obese patients.

Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61(3):230-234.

|

| 12 |

Amin MA, Abdelraouf HS, Ahmed AH.

Comparative study between tracheal ultrasound and pleural ultrasound for confirmation of endotracheal tube position.

Scientific Journal of Al-Azhar Medical Faculty, Girls. 2021;5(1):217-222.

|

| 13 |

Muslu B, Sert H, Kaya A, et al.

Use of sonography for rapid identification of esophageal and tracheal intubations in adult patients.

J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(5):671-676.

|

| 14 |

Chou HC, Tseng WP, Wang CH, et al.

Tracheal rapid ultrasound exam (T.

Resuscitation. 2011;82(10):1279-1284.

|

| 15 |

Pfeiffer P, Bache S, Isbye DL, Rudolph SS, Rovsing L, Børglum J.

Verification of endotracheal intubation in obese patients—temporal comparison of ultrasound vs.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56(5):571-576.

|

| 16 |

Chowdhury AR, Punj J, Pandey R, Darlong V, Sinha R, Bhoi D.

Ultrasound is a reliable and faster tool for confirmation of endotracheal intubation compared to chest auscultation and capnography when performed by novice anaesthesia residents—a prospective controlled clinical trial.

Saudi J Anaesth. 2020;14(1):15-21.

|

| 17 |

Kuppusamy A, Mirunalini G, Koka MV, Ramamurthy B.

Comparison of real-time ultrasound with capnography to confirm endotracheal tube position in patients in critical care unit—a cross-sectional study.

Bali J Anesth. 2022;6(1):43-48.

|

| 18 |

Abhishek C, Munta K, Rao SM, Chandrasekhar CN.

End-tidal capnography and upper airway ultrasonography in the rapid confirmation of endotracheal tube placement in patients requiring intubation for general anaesthesia.

Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61(6):486-489.

|