Abstract

Background

Accidental awareness during general anesthesia (AAGA) is rare but can lead to psychological distress, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Limited data exists from East Asia, where cultural factors may influence symptom expression. This study examined the incidence, contributing factors, and one-year psychological outcomes of AAGA in a Taiwanese tertiary center.

Methods

We reviewed 18,976 patients who received general anesthesia at National Taiwan University Hospital in 2020. AAGA cases were identified via routine postoperative interviews and anesthesia record reviews. One year later, follow-up telephone interviews were conducted using the Chinese version of the PTSD Symptom Scale - Interview for DSM-5 (PSS-I-5), along with a culturally adapted emotional experience questionnaire.

Results

Seven patients (0.037%) were classified as definite or possible AAGA. Most events occurred during intubated general anesthesia or propofol sedation. Human errors, such as delayed drug administration or intravenous disconnection, contributed to over half the cases. Of the four patients who completed one-year PTSD screening, none met diagnostic criteria, though two recalled vivid intraoperative experiences and later changed their anesthesia preferences. Cultural factors may have influenced symptom reporting.

Conclusion

Though no PTSD diagnoses were identified, AAGA had lasting effects on patient preferences. The findings highlight the need for structured follow-up and culturally sensitive care to better recognize and manage AAGA-related distress.

Keywords

accidental awareness during general anesthesia (AAGA), anesthesia, cultural psychiatry, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Introduction

Accidental awareness during general anesthesia (AAGA) is a rare but potentially traumatic complication defined by unintended intraoperative consciousness followed by explicit postoperative recall. Although estimates vary based on methodology, a national audit in the United Kingdom (e.g., the United Kingdom’s 5th National Audit Project [NAP5]) reported an incidence of approximately 1 in 19,000 cases, 1 while earlier studies in the United States and Sweden observed higher rates ranging from 0.1% to 0.2%. 2,3

The psychological consequences of AAGA may be profound. Patients may report distressing recollections, poor sleep, nightmares, decreased appetite, and, in some cases, distressing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 4-6 In major larger trials, including B-Unaware (anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index), BAG-RECALL (BIS or anesthesia gas to reduce explicit recall), and MACS (Michigan Awareness Control Study), up to 43% of patients with definite or possible awareness met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. 7-10 The Brice interview remains a foundational method for identifying awareness, 11 though retrospective detection may underestimate milder or culturally suppressed symptoms.

Despite global interest, AAGA remains underreported in East Asian contexts. A survey in Japan revealed a lower reported incidence (0.028%) of PTSD, which may reflect cultural norms surrounding emotional expression, stigma, and medical hierarchy. 12 In Taiwanese society, patients may hesitate to disclose psychological discomfort, either due to perceived expectations of stoicism or deference to authority. As a result, trauma-related symptoms may be expressed somatically or suppressed altogether.

However, in Asia, most studies have relied solely on questionnaire surveys, with limited prospective or long-term follow-up data, including from Taiwan. This gap underscores the need for culturally contextualized studies that integrate both clinical classification and psychological outcomes.

To date, limited data exist on the incidence and long-term psychological effects of AAGA in Taiwan. Moreover, there is a lack of structured institutional responses that account for the cultural nuances in trauma expression and help-seeking behavior. This study aimed to (1) estimate the incidence of AAGA in a tertiary center in Taiwan, (2) identify perioperative risk factors, and (3) assess one-year psychological outcomes. We further sought to explore how cultural factors may influence patients’ interpretation and reporting of intraoperative awareness.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study used a retrospective–prospective hybrid cohort design conducted at a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. AAGA cases were identified retrospectively from patients who underwent general anesthesia between January 1 and December 31, 2020. These cases were then followed up prospectively via structured interviews conducted approximately one year after the index surgery. The study was approved by the institutional review board, with a waiver of informed consent for retrospective data review and verbal consent obtained for follow-up interviews.

Retrospective Study

Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). All patients who underwent surgery between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020, were included for screening.

This study was reviewed and approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 20211104RINB). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, which involved only the analysis of existing medical records without any impact on patient care. This study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (see Table A1 in Appendix).

We accessed the hospital’s electronic medical records to retrospectively identify all surgical patients in 2020 who may have experienced AAGA. Postoperative interview records were screened to identify suspected AAGA cases. Data extracted included patient characteristics, anesthesia type, intraoperative parameters, and potential contributing factors to AAGA.

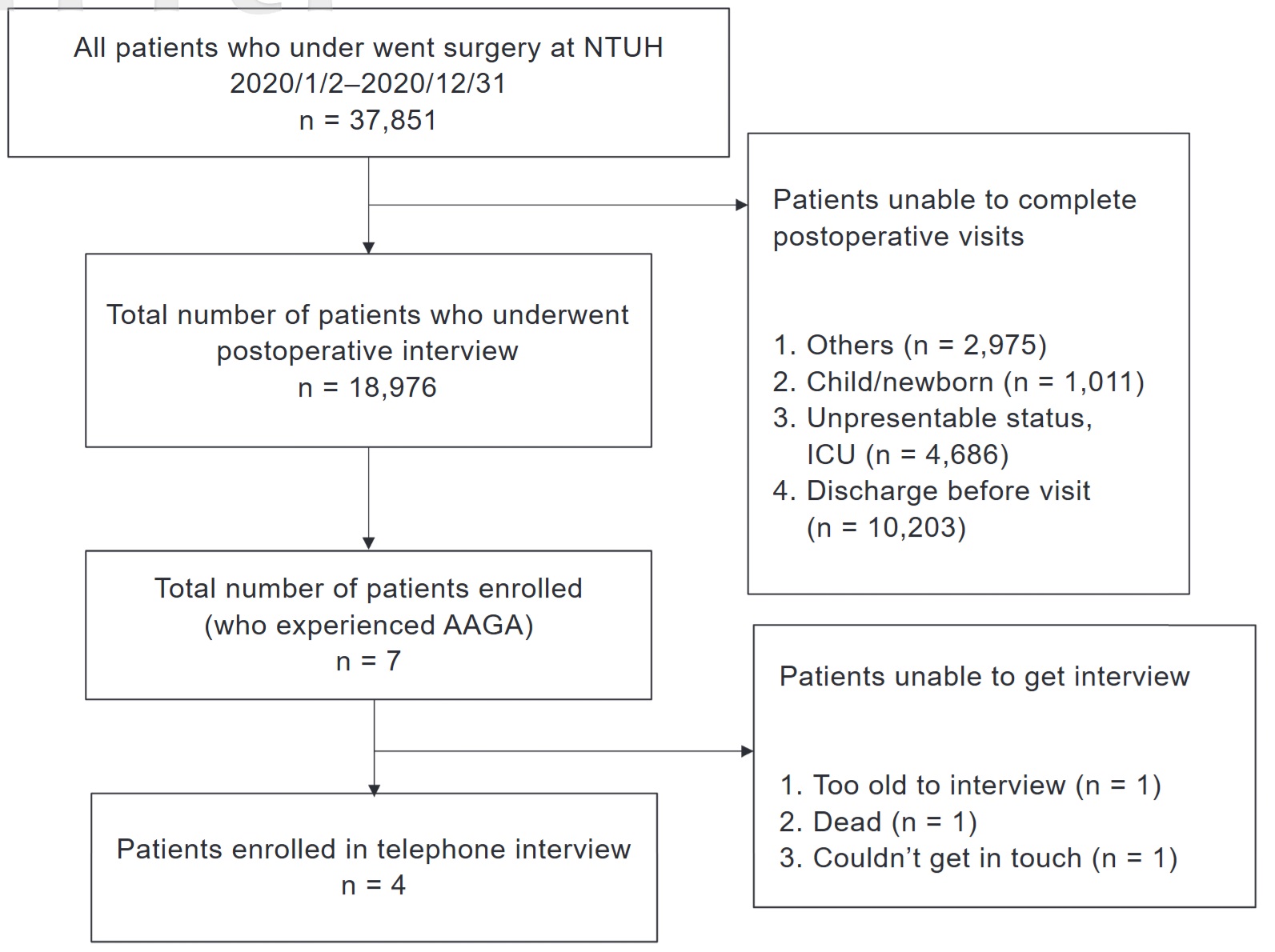

Patients were identified through standardized postoperative bedside interviews, which are routinely conducted following surgery. These interviews assess pain intensity, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, urinary retention, soft tissue injury, suspected AAGA, sensory or motor dysfunction, delirium, and satisfaction. Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients who underwent surgery between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020; and (2) patients who received general anesthesia. Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) postoperatively; (2) patients discharged before completing the postoperative interview; and (3) patients unable to participate in postoperative assessments, such as newborns (see Figure 1).

Download full-size image

Abbreviation: AAGA, awareness during general anesthesia.

The primary outcome was patient-reported suspected AAGA during any stage of the operation, as identified through standardized postoperative interviews. For all AAGA cases, their electronic anesthesia records were reviewed to examine intraoperative anesthetic agent administration, recorded at 3-minute intervals. Additional data were collected from electronic medical records, including preoperative assessments, surgical procedure, anesthesia technique, premedication and maintenance agents, intraoperative anesthetic concentrations, and postoperative evaluations.

Information pertaining to the patients’ baseline characteristics, including age, sex, weight, anesthesia type, anesthesia medication, and operation method, was collected. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided

Prospective Study

One-Year Follow-Up

One year after surgery, we conducted telephone follow-up interviews with all seven patients who had reported suspected AAGA to further explore their experiences and individual psychological characteristics. This prospective follow-up was reviewed and approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 202201078RIND).

To assess the psychological impact of AAGA, we conducted structured follow-up interviews using two instruments: the PTSD Symptom Scale—Interview for DSM-5 (PSS-I-5), 13 administered in Mandarin, and a modified version adapted for our patient population. The modified interview placed greater emphasis on perioperative experiences, specifically exploring patients’ emotional responses during and after surgery. Both instruments included questions on personality traits, intraoperative awareness, and psychological status one year postoperatively. The contents of the modified questionnaire are detailed in Table 1.

|

中文版本 |

English version |

|

|---|---|---|

|

About personality |

本身是哪一種人格?(樂觀、悲觀、緊張型、隨遇而安型) |

How would you describe your personality? (Optimistic, Pessimistic, Nervous, Sensitive, Oblivious?) |

|

以前有沒有精神相關疾病或用藥(安眠藥、抗焦慮藥) |

Were you under anti-psychotic medication? (Hypnotics, Anxiolytic) |

|

|

現在有沒有精神相關疾病或用藥(安眠藥、抗焦慮藥),有變嚴重或減輕? |

Are you currently under anti-psychotic medication? (Hypnotics, Anxiolytic) Were there any changes in dosage? |

|

|

About operation |

記得上一次手術是什麼時候?做什麼手術嗎? |

Do you remember when was the last time you received an operation? What operation was it? |

|

記得當時手術前後心情如何 |

What was your mood before and after the operation? |

|

|

如果記得當時手術中好像有醒來,是否有聽到什麼/感覺到什麼、試圖做出什麼動作/聲音等等。大概是哪一個時間點、多久 |

If you recalled waking up during the operation, what was the timing? What did you hear, see, feel, or try to do in that period of time |

|

|

About post-operation |

手術後有無時常做惡夢、淺眠 |

Do you experience nightmares and poor sleeping quality frequently after the surgery? |

|

這一年有什麼跟以前不一樣的地方(開刀後生活品質?心情?活動力?體重?) |

Was there any difference compared to your life prior to this operation (Quality of life? Mood? Activity status? Body weight?) |

Results

Retrospective Study

The incidence rate of AAGA in our study was 0.037% (7/18,976) (See Table 2). General anesthesia with tracheal intubation was conducted in four patients (57%), while sedation with propofol infusion was conducted in the other three patients. Two out of seven patients received a combined neuromuscular block (29%). Human errors (reversible cause) that cause failure to deliver sufficient anesthetic agent to the body were judged in four patients (57%). Two out of the four patients were maintained with inhalation anesthetics along with delayed administration of maintenance agents, while the other two received propofol infusion and experienced inadvertent intravenous (IV) catheter displacement. Causes for other patients include two sedations and one unknown reason.

|

Characteristic |

Number |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Total (18,976) |

||

|

Cases of AAGA |

7 |

|

|

Incidence rate |

0.037 |

|

|

Age, years |

||

|

Mean |

66.9 |

|

|

SD |

19.6 |

|

|

Sex |

||

|

Female |

4 |

57 |

|

Male |

3 |

43 |

|

Weight (kg) |

||

|

Mean |

70.6 |

|

|

SD |

20.3 |

|

|

BMI |

||

|

Mean |

28.4 |

|

|

SD |

6.37 |

|

|

Anesthesia type |

||

|

GA |

4 |

57 |

|

Sedation with propofol |

3 |

43 |

|

AAGA type |

||

|

Reversible cause |

4 |

57 |

|

Suspected |

3 |

43 |

Abbreviations: AAGA, accidental awareness during general anesthesia; BMI, body mass index; GA, general anesthesia; SD, standard deviation.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system indicated patients’ preanesthesia medical co-morbidities. The severity increases from classes one to six. In our study, all patients were between classes 2 to 3, which indicated a moderate level.

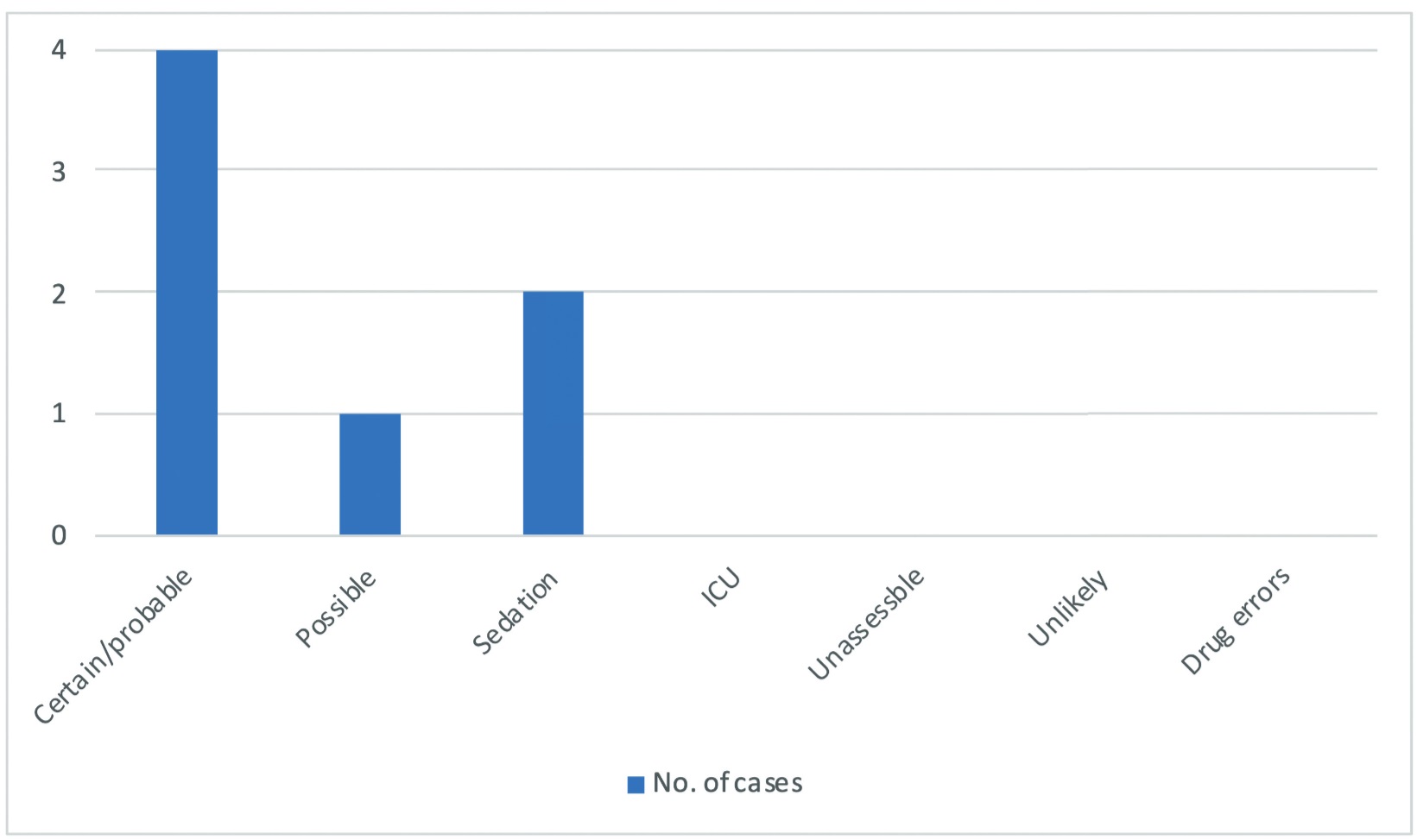

According to NAP5, AAGA cases were classified into several types (Figure 2). Most of the cases were compatible with the statements when reviewing the electronic medical records, such as IV out before or during the surgery, or delayed administration of maintenance agents. These were classified as “certain/probable AAGA” cases. In the other three cases, two were classified as “sedation”, where AAGA happened under sedation. This reveals that a sedation-only operation may be a risk factor for AAGA. One case was classified as a possible case, with no certain reason that could be well explained. Two patients had changed the anesthesia type to spinal anesthesia after this operation experience.

Download full-size image

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Among all seven cases, obesity was found in four patients (57%), alcohol use in one (14%), and smoking habit in one (14%). The above risk factors also contribute to potential risks for AAGA. None of the patients were monitored with a processed electroencephalography (Table 2).

Prospective Study

A total of seven patients were final candidates for telephone contact. However, one patient passed away before our one-year follow-up, one patient was too elderly to undergo the interview, and one patient could not be contacted due to a change in telephone number. Ultimately, four patients were successfully interviewed, consisting of one woman and three men.

Patients who experienced AAGA were contacted one year after the operation. A table for seven tele-interviews were conducted over the phone, and four interviews were accomplished. According to the interviews, two of the four participants could clearly remember the scene and settings during anesthesia, while the other two participants could not recall any memory or sensation related to the anesthesia process. They also denied experiencing AAGA and led a smooth and stable life without psychologically related sequela.

One notable case involved a 45-year-old woman with a body mass index of 31 who underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the right clavicle. During anesthetic induction, IV access failed, resulting in an incomplete induction. The patient subsequently experienced intraoperative awareness and reported being fully conscious throughout the endotracheal intubation process. She vividly recalled specific auditory details, including medical staff requesting the endotracheal tube and discussing the surgical plan and required instruments. Loss of awareness occurred only after the administration of sevoflurane.

Another case involved a 48-year-old man who underwent loop ileostomy closure under general anesthesia. Induction was achieved with propofol and cisatracurium, followed by maintenance with sevoflurane and desflurane. The patient reported experiencing awareness during the procedure; however, chart review revealed no apparent anesthetic error or mechanical malfunction. During the one-year follow-up interview, the patient reflected:

This response illustrates a notable degree of psychological resilience and a culturally embedded trust in medical authority, even in the face of a distressing intraoperative experience. The case underscores the variability in psychological responses to AAGA and highlights the value of follow-up assessments in identifying individual support needs.

Discussion

In this study, the incidence of AAGA was 0.037%, lower than previously reported rates in the United States (0.1% to 0.2%) and China (0.41%). 14 Globally, about two-thirds of AAGA cases occur during the dynamic phases of anesthesia, induction, and emergence, often linked to insufficient anesthetic concentration in the brain. However, one-third of cases occur during the maintenance phase despite stable anesthetic delivery. 1

We categorized AAGA causes into two primary groups: failure to deliver anesthetic agents (57%) and unknown patient-related factors, such as drug resistant or a genetic factor that causes patients to easily awake during the operation (43%). Although the sample size limited statistical comparisons, two of the three cases attributed to unknown factors occurred during sedation-only procedures, suggesting a possible elevated risk. Risk factors such as neuromuscular blockade (29%) and obesity (57%) were consistent with those previously reported. 15

The distress associated with AAGA may influence patients’ subsequent anesthesia decisions. Prior studies have shown that individuals with AAGA are five times more likely to experience it again. 16 In our study, four patients had received surgery again, and two of them (50%) had changed their anesthesia type to spinal anesthesia. These findings motivated a departmental quality improvement initiative including structured debriefings and AAGA risk screening during preoperative assessment.

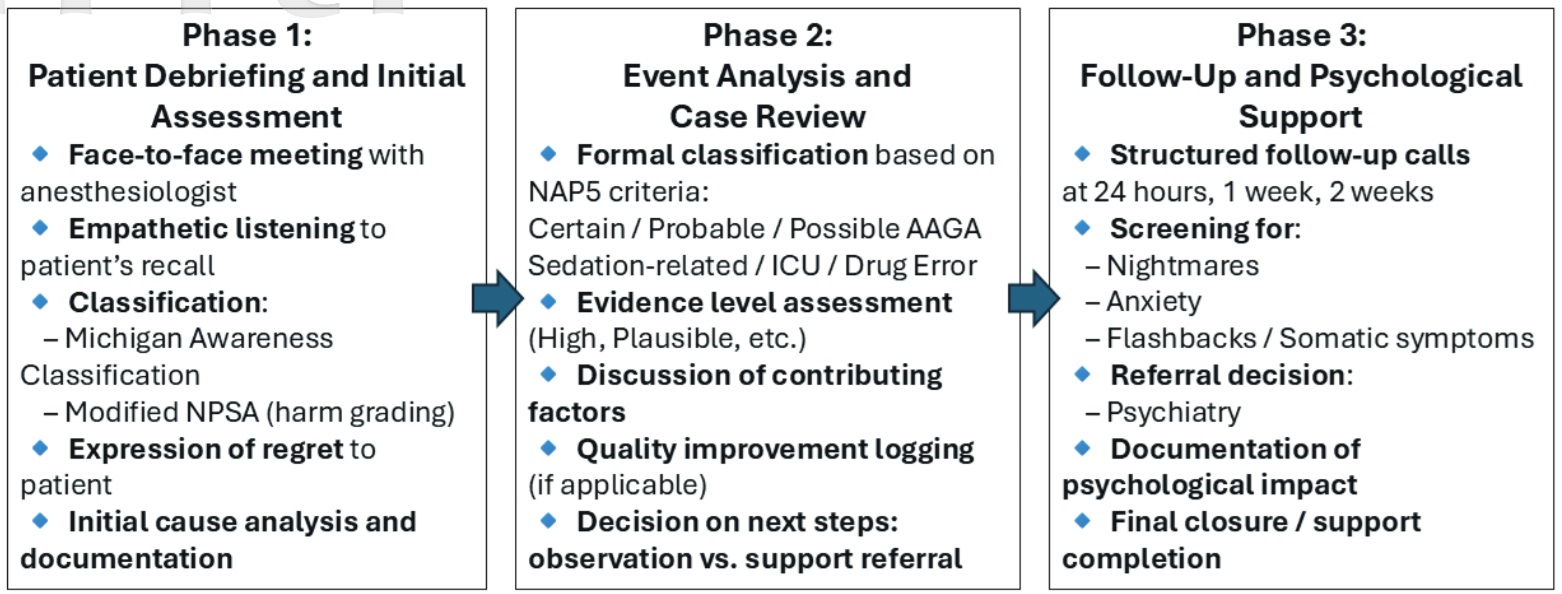

To address reported AAGA cases, our institution has implemented a structured support protocol aligned with the NAP5 on AAGA (Figure 3). 15 When AAGA is suspected, patients receive face-to-face interviews and structured evaluations based on a modified NAP5 flowchart to identify contributing factors. Psychiatric consultation is available when indicated to ensure timely psychological support.

Download full-size image

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; NPSA, National Patient Safety Agency.

Building on this protocol, we established a three-phase institutional response: (1) bedside debriefing with empathetic communication and harm classification, (2) formal case review using NAP5 criteria, and (3) psychological follow-ups at 24 hours, 1 week, and 2 weeks with referrals as needed. To further strengthen our approach, we adopted a trauma-informed care (TIC) framework. TIC emphasizes patient safety, trust, empowerment, and cultural sensitivity, principles particularly relevant in East Asian settings where emotional expression may be suppressed and deference to medical authority is common. Training staff to recognize psychological trauma and promote shared decision-making supports compassionate care and reduces stigma around mental health.

While the underlying mechanisms of AAGA remain poorly understood, no single preventive strategy has proven consistently effective. Monitoring techniques such as electroencephalographic monitoring with bispectral index 7 , end-tidal anesthetic gas concentration, and benzodiazepine use 9,17 have been proposed, but none reliably eliminate AAGA risk. As recommended by NAP5, early postoperative assessment, case analysis, and sustained psychological support are key components of management. 15 Early postoperative meetings are critical for identifying AAGA and enabling further management. 6 Our relatively low detection rate may be attributed to reliance on a single postoperative interview, which risks missing cases. Prior studies advocate for multiple follow-ups, up to three, often incorporating the Brice interview to enhance sensitivity. 18

Remarkably, none of the four patients in our study met PTSD diagnostic criteria one year after surgery, although the literature reports PTSD rates after AAGA ranging from 0% to 71%. 4 This may reflect cultural differences in trauma conceptualization and expression. The Chinese version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale Interview (PSS-I), though validated, relies on direct symptom self-reporting. 19 In East Asian societies, psychological distress may be downplayed due to cultural norms that prioritize emotional restraint and social harmony. Patients may provide vague or non-disclosive answers such as “non-relevant” or “cannot recall,” which could mask distress rather than indicate absence of symptoms. 20-22

Cultural variation significantly influences how trauma is conceptualized and expressed. While Western frameworks typically emphasize symptoms like flashbacks, hyperarousal, and avoidance, many Asian and African cultures interpret trauma through somatic complaints, spiritual beliefs, or collective identity. 16,18 PTSD prevalence in the general U.S. population is estimated at 6%–8%, compared to only 0.028% in Japan, likely reflecting cultural differences in emotional expression, help-seeking behavior, and symptom interpretation. 12

These findings highlight the need for culturally sensitive PTSD assessments. Standardized tools like the PSS-I, which are based on Western psychiatric models, may underestimate trauma-related distress in East Asian populations unless adapted to local cultural norms. Although the Chinese version of PSS-I provides a structured diagnostic framework, its reliance on closed-ended questions, such as “Have you experienced nightmares?” may constrain responses in individuals reluctant to disclose emotional discomfort. In contrast, our use of open-ended questions alongside the PSS-I (Table 1) encourages patients to reflect on their perioperative experiences and share details that might otherwise be withheld. This format is particularly suitable for Asian populations, who, as previously discussed, may suppress negative emotions or avoid open discussion of distress. Our approach allows for more nuanced and accurate insights into the psychological impact of AAGA, highlighting key differences from conventional PTSD questionnaires. By supplementing standardized tools like the PSS-I with culturally attuned, open-ended interviews, our approach offers a promising model for more accurate psychological assessments in East Asian contexts. Future research should further develop mixed-method or culturally tailored assessment strategies to improve the identification and management of AAGA-related psychological distress.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size (n = 7) limits statistical power and generalizability. Second, the reliance on a single postoperative interview may have led to under-detection of AAGA, particularly in patients hesitant to report distress. Third, recall bias and emotional suppression may have influenced patients’ willingness to disclose intraoperative experiences or psychological symptoms. Three patients were lost to follow-up due to death, age, or inability to contact, reducing the number of complete 1-year assessments. Additionally, the modified Brice questionnaire, the modified Brice questionnaire, commonly used to detect intraoperative awareness, was not implemented. Finally, as this study was designed as a quality improvement initiative rather than a powered epidemiologic investigation, it was not intended to detect statistical associations between risk factors and AAGA incidence.

Conclusion

This study is the first in Asia to examine AAGA with structured 1-year follow-up data. The observed incidence (0.037%) was lower than that reported in Western countries. Although no patients met PTSD criteria, cultural factors likely influenced the expression and reporting of psychological symptoms. Notably, half of the patients who underwent subsequent surgeries changed their anesthetic modality, suggesting lingering effects of their intraoperative experiences.

Our findings emphasize the need for culturally adapted PTSD assessment tools, multi-timepoint postoperative interviews, and trauma-informed screening protocols to better support patients at risk of AAGA. Future large-scale, longitudinal research is essential to clarify modifiable risk factors and develop prevention strategies tailored to diverse cultural and clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Edna B. Foa of the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Professor Sue-Huei Chen for their kind permission to use the Chinese version of the PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview (PSS-I) in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

| 1 |

Pandit JJ, Cook TM, Jonker WR, O’Sullivan E; 5th National Audit Project (NAP5) of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.

A national survey of anaesthetists (NAP5 Baseline) to estimate an annual incidence of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia in the UK.

Anaesthesia. 2013;68(4):343-353.

|

| 2 |

Sebel PS, Bowdle TA, Ghoneim MM, et al.

The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States study.

Anesth Analg. 2004;99(3):833-839.

|

| 3 |

Bischoff P, Rundshagen I.

Awareness under general anesthesia.

Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(1-2):1-7.

|

| 4 |

Aceto P, Perilli V, Lai C, et al.

Update on post-traumatic stress syndrome after anesthesia.

Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(13):1730-1737.

|

| 5 |

Leslie K, Chan MTV, Myles PS, Forbes A, McCulloch TJ.

Posttraumatic stress disorder in aware patients from the B-aware trial.

Anesth Analg. 2010;110(3):823-828.

|

| 6 |

Tasbihgou SR, Vogels MF, Absalom AR.

Accidental awareness during general anaesthesia - a narrative review.

Anaesthesia. 2018;73(1):112-122.

|

| 7 |

Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al.

Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index.

N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1097-1108.

|

| 8 |

Avidan MS, Palanca BJ, Glick D, et al.

Protocol for the BAG-RECALL clinical trial: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial to determine whether a bispectral index-guided protocol is superior to an anesthesia gas-guided protocol in reducing intraoperative awareness with explicit recall in high risk surgical patients.

BMC Anesthesiol. 2009;9:8.

|

| 9 |

Mashour GA, Shanks A, Tremper KK, et al.

Prevention of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall in an unselected surgical population: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial.

Anesthesiology. 2012;117(4):717-725.

|

| 10 |

Whitlock EL, Rodebaugh TL, Hassett AL, et al.

Psychological sequelae of surgery in a prospective cohort of patients from three intraoperative awareness prevention trials.

Anesth Analg. 2015;120(1):87-95.

|

| 11 |

Pollard RJ, Coyle JP, Gilbert RL, Beck JE.

Intraoperative awareness in a regional medical system: a review of 3 years’ data.

Anesthesiology. 2007;106(2):269-274.

|

| 12 |

Morimoto Y, Nogami Y, Harada K, Tsubokawa T, Masui K.

Awareness during anesthesia: the results of a questionnaire survey in Japan.

J Anesth. 2011;25(1):72-77.

|

| 13 |

Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, et al.

Psychometric properties of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale Interview for DSM-5 (PSSI-5).

Psychol Assess. 2016;28(10):1159-1165.

|

| 14 |

Xu L, Wu AS, Yue Y.

The incidence of intra-operative awareness during general anesthesia in China: a multi-center observational study.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53(7):873-882.

|

| 15 |

Pandit JJ, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al.

5th National Audit Project (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia: summary of main findings and risk factors.

Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(4):549-559.

|

| 16 |

Aranake A, Gradwohl S, Ben-Abdallah A, et al.

Increased risk of intraoperative awareness in patients with a history of awareness.

Anesthesiology. 2013;119(6):1275-1283.

|

| 17 |

Sandin RH, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Lennmarken C.

Awareness during anaesthesia: a prospective case study.

Lancet. 2000;355(9205):707-711.

|

| 18 |

Brice DD, Hetherington RR, Utting JE.

A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anaesthesia.

Br J Anaesth. 1970;42(6):535-542.

|

| 19 |

Wu TY, Sun FJ, Tung KY, Yeh HT, Liu CY.

Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview for patients with severe burn in Taiwan.

J Burn Care Res. 2018;39(4):507-515.

|

| 20 |

Korn CW, Fan Y, Zhang K, Wang C, Han S, Heekeren HR.

Cultural influences on social feedback processing of character traits.

Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:192.

|

| 21 |

Heine SJ, Hamamura T.

In search of East Asian self-enhancement.

Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2007;11(1):4-27.

|

| 22 |

Murata A, Moser JS, Kitayama S.

Culture shapes electrocortical responses during emotion suppression.

Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8(5):595-601.

|

Appendix

|

Outline |

Item No. |

Recommendation |

Page No. |

Relevant text from manuscript |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Title and abstract |

1 |

(1) Indicate the study ’ s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract |

1 |

Title |

|

(2) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found |

3 |

Abstract |

||

|

Introduction |

||||

|

Background/rationale |

2 |

Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported |

4-5 |

Introduction |

|

Objectives |

3 |

State-specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses |

4-5 |

Introduction |

|

Methods |

||||

|

Study design |

4 |

Present key elements of the study design early in the paper |

6-7 |

Study design |

|

Setting |

5 |

Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

6 |

Settings |

|

Participants |

6 |

(1)

|

7 |

Participants |

|

(2)

|

NA |

|||

|

Variables |

7 |

Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable |

7 |

Outcome measurement |

|

Data sources/ measurement |

8 * |

For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe the comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group |

7 |

Outcome measurement |

|

Bias |

9 |

Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias |

15 |

Limitations |

|

Study size |

10 |

Explain how the study size was arrived at |

7 |

Participants |

|

Quantitative variables |

11 |

Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why they were chosen |

7 |

Participants |

|

Statistical methods |

12 |

(1) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding |

8 |

Statistical analysis |

|

(2) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions |

8 |

Statistical analysis |

||

|

(3) Explain how missing data were addressed |

8 |

Statistical analysis |

||

|

(4)

|

8 |

Statistical analysis, Prospective study |

||

|

(5) Describe any sensitivity analyses |

8 |

Statistical analysis |

||

|

Results |

||||

|

Participants |

13 * |

(1) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analysed |

9 |

Retrospective study |

|

(2) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage |

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

||

|

(3) Consider the use of a flow diagram |

Figure 1 |

|||

|

Descriptive data |

14 * |

(1) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders |

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

|

(2) Indicate the number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest |

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

||

|

(3)

|

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

||

|

Outcome data |

15 * |

|

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

|

|

NA |

|||

|

|

NA |

|||

|

Main results |

16 |

(1) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included |

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

|

(2) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized |

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

||

|

(3) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period |

NA |

|||

|

Other analyses |

17 |

Report other analyses done—e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses |

9-11 |

Retrospective study, prospective study |

|

Discussion |

||||

|

Key results |

18 |

Summarise key results with reference to study objectives |

12-13 |

Discussion |

|

Limitations |

19 |

Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both the direction and the magnitude of any potential bias |

15 |

Limitations |

|

Interpretation |

20 |

Give a cautious overall interpretation of results, considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence |

12-14 |

Discussion |

|

Generalisability |

21 |

Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results |

12-14 |

Discussion |

|

Other information |

||||

|

Funding |

22 |

Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based |

NA |

Give information separately for cases and controls in case-control studies and, if applicable, for exposed and unexposed groups in cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Note: An Explanation and Elaboration article discusses each checklist item and gives methodological background and published examples of transparent reporting. The STROBE checklist is best used in conjunction with this article (freely available on the websites of

PLoS Medicine,

Annals of Internal Medicine,

and

Epidemiology

).

Information on the STROBE Initiative is available at

www.strobe-statement.org.