Abstract

Background

Propofol has been associated with metabolic acidosis in case reports. However, the results of studies in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery are controversial. On the other hand, there have been no randomized controlled studies addressing this issue in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). In this study, we investigated whether propofol was associated with metabolic acidosis in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB.

Methods

Forty patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB were randomly assigned to receive total anesthesia with propofol (intervention group) or sevoflurane (control group), respectively. Except for this, the anesthetic and surgical management was the same in all patients. The primary outcomes were the changes in arterial blood pH, base excess, HCO 3 - , and lactate levels during surgery. The secondary outcomes included serum aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), urea, and creatinine levels, as well as the proportion of patients with increased liver enzymes and kidney damage at the end of surgery, and the proportion of patients with arrhythmia during surgery.

Results

The rate of metabolic acidosis with high lactate at the end of surgery in the propofol group (intervention group) was statistically higher than that in the sevoflurane group (control group). Nevertheless, no difference in serum AST, ALT, urea, and creatinine levels between the two groups, and the proportions of patients with increased liver enzymes and kidney damage at the end of surgery, as well as the proportion of patients with arrhythmia during surgery.

Conclusion

Total anesthesia with propofol was associated with metabolic acidosis but did not significantly affect increased liver enzymes, kidney damage, and arrhythmias when compared with the control group in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB.

Keywords

cardiac surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, metabolic acidosis, propofol, sevoflurane

Introduction

Propofol is commonly used for anesthesia in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in addition to volatile anesthetics due to its myocardial protective properties. 1-4 Nevertheless, according to evidence provided by case reports and studies, high doses and prolonged use of propofol may cause a rare complication called propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS). 5-14 This syndrome is mainly manifested by otherwise unexplained metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia, elevated liver enzymes, acute kidney injury, cardiac dysfunction, and can be fatal. 9,10,15-18 Metabolic acidosis associated with propofol anesthesia may be a precursor of PRIS and is characterized by increased lactate levels. 19 Besides, some studies showed that metabolic acidosis could even develop in patients receiving low-dose and short-term infusions of propofol. 14,20-22 Therefore, early recognition of metabolic/lactic acidosis in patients receiving propofol infusions may play a crucial role in the interruption or prevention of further development of PRIS. However, several retrospective studies in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery have yielded controversial results on the effect of propofol on metabolic acidosis. 19-21 Furthermore, in cardiac surgery patients with CPB, there are only a few case reports but no randomized controlled studies addressing the effect of propofol used during the entire anesthesia process on metabolic acidosis. 23,24 Hence, we designed a randomized controlled clinical intervention study to evaluate the effect of propofol used during the entire anesthesia process on metabolic acidosis in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether total anesthesia with propofol (administered throughout the entire anesthetic procedure) resulted in metabolic acidosis when compared with sevoflurane. As secondary endpoints, we also evaluated other signs of PRIS, such as elevated liver enzymes, kidney damage, and arrhythmia.

Methods

Patient Population

In this study, 46 patients aged 18 years and older scheduled for cardiac surgery with CPB between August 2017 and January 2020 were enrolled. Exclusion conditions included patients with arrhythmias, preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40%, hemodynamic instability with the need for medical or mechanical support, pre-existent metabolic acidosis, and those with severe systemic diseases involving the renal and hepatic systems and respiratory disease, history of drug allergy or malignant hyperthermia, history of nervous system diseases or psychiatric disturbance, withdrawal of consent and reoperation. Additionally, patients have had events associated with tissue hypoxia-induced lactic acidosis, including inadequate arterial saturation or a sudden decrease in hemoglobin < 7 g/dL, and massive bleeding (transfusion of > 10 units of packed red blood cells or estimated blood loss > 70 mL/kg) was also excluded.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of 108 Military Central Hospital, Vietnam (275/QD-V108) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent also.

Study Groups

The patients were randomly assigned to the propofol group (intervention group) or the sevoflurane group (control group) of equal size according to computer-generated randomization. The propofol group and the sevoflurane group were anaesthetized by propofol infusion or by sevoflurane inhalation during the entire anesthetic process, respectively. A computer-generated random code determined which anesthetic protocol was identified by each treatment number. Subjects were assigned the treatment numbers in ascending chronological order of admission to the study. The participant randomization assignment was concealed in an envelope until the start of anesthesia. All other participants, such as surgeons, research assistants, and other medical staff in the intensive care unit (ICU) and the ward, were blinded to treatment assignment for the duration of the study.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

The primary endpoints were the changes in arterial blood pH, base excess (BE), HCO 3 - , and lactate levels during surgery. Secondary endpoints were serum aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), urea, and creatinine levels, and the proportion of patients with increased liver enzymes and kidney damage at the end of surgery, as well as the proportion of patients with arrhythmia during surgery.

Anesthesia and Surgery

Prior to induction of anesthesia, routine monitoring has been established, including five-lead electrocardiography, invasive radial arterial pressure, central venous pressure, pulse oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure, esophageal temperature, and urine output. In addition, hemodynamic monitoring (with the FloTrac/EV1000 platform), bispectral index (BIS) monitoring (measuring depth of anesthesia), and transesophageal echocardiography were also performed. Premedication was the same in all patients in both groups, with 0.04 mg kg

-1

midazolam administered intravenously 30 minutes before induction of anesthesia. In the propofol group (intervention group), anesthesia was induced with a target-controlled infusion (TCI) of fentanyl at 2 ng mL

-1

and of propofol at 1.5 μg mL

-1

, increased 0.5 μg mL

-1

every two minutes if patients had not lost consciousness. In the sevoflurane group (control group), anesthesia was induced with a TCI of fentanyl at 2 ng mL

-1

; sevoflurane was initially started at 8%, and when the patient was asleep, it was lowered and maintained at 1.0 ± 0.2 minimum alveolar concentration (MAC). In both groups, muscle paralysis was obtained with 0.1 mg kg

-1

pipecuronium bromide to facilitate tracheal intubation. Mechanical ventilation was adjusted in assist-control mode with a tidal volume of 6–8 mL kg

-1

body weight, respiratory frequency was adjusted to obtain an end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure of 35–45 mmHg, inspired oxygen fraction was set at 0.5, and positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cmH

2

O was set as the default. According to group allocation, anesthesia was maintained with TCI of fentanyl at 2 ng mL

-1

,

TCI of propofol at 3–4 μg mL

-1

, and pipecuronium bromide 0.04 mg kg

-1

every 2 hours (the propofol group) or TCI of fentanyl at 2 ng mL

-1

, sevoflurane 1.0 ± 0.2 MAC and pipecuronium bromide 0.04 mg kg

-1

every 2 hours (the sevoflurane group). Next, all patients were initiated with a sternotomy incision by the same group of cardiac surgeons. The patients were anticoagulated with 300 IU kg

-1

of heparin to provide an activated coagulation time higher than 400 seconds. CPB was performed at normal body temperature (36–37°C) after the cannulation of the aorta and right atrium and maintained at a cardiac index of 2.4 L min

-1

m

-2

of body surface area with a Sarns heart–lung roller pump (Terumo CV Systems, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Myocardial protection during aortic cross-clamping was obtained by a warm blood solution administered into the aortic root every 30 minutes. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) was maintained at more than 65 mmHg by increasing the pump flow rate or a bolus of phenylephrine (100 μg) or norepinephrine (5 μg). During CPB, sevoflurane was administered through the oxygenator. In both groups, the depth of anesthesia before, during, and after CPB was controlled at BIS 40–60 by adjusting inhaled sevoflurane concentration or the infusion rate of propofol, respectively. After aortic unclamping, the heart was defibrillated if the sinus rhythm did not resume spontaneously. Serum glucose levels were controlled with intermittent administration of insulin (intravenous bolus of 5–10 UI). Patients with a hemoglobin value below 8 g dL

-1

received homologous red blood cell transfusions. At the end of CPB, the effect of heparin was reversed with protamine sulphate in a 1:1 ratio. And at the end of surgery, patients were transferred to the ICU, where they were sedated with midazolam/fentanyl and extubated when they met the criteria for extubation.

Data Collection and Definitions

All data were recorded by a clinical data manager who was blinded to patient allocation. The following perioperative variables were recorded: age, gender, bodyweight, height, body mass index, personal medical history, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) II, type of cardiac surgery, preoperative LVEF, hemodynamic parameters, need for use of vasopressor, need for intraoperative fluid and blood transfusion, operating time, anesthesia time, aortic clamping time, CPB time. In addition, serum AST, ALT, urea, and creatinine levels before and at the end of surgery, the proportion of patients with increased liver enzymes and kidney damage at the end of surgery, and the proportions of patients with different types of arrhythmias during surgery were also recorded.

Blood samples were collected for arterial blood gas testing at the following times: immediately before starting induction (base), 5 minutes after heart beat recovery, end of CPB, and end of surgery.

In this study, hemodynamic parameters were assessed by arterial pressure wave analysis on the FloTrac/EV1000 platform (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA). At the same time, arterial blood gas analysis was performed by electrochemical methods on GEM Premier 3500 (Instrumentation Laboratory, Massachusetts, USA). Serum AST, ALT, urea, and creatinine were measured by the spectrophotometric method on the Cobas c501 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) biochemistry module.

Metabolic acidosis was defined as an arterial pH < 7.35 and BE ≤ –2 mEq L -1 or serum lactate ≥ 3 mmol L -1 . Although PRIS is characterized by a BE value that is more negative than the aforementioned value, the goal of this study was to detect an early indicator of PRIS. In addition, the initial BE was –2 to –3 mEq L -1 in several of the case reports regarding PRIS 19,20.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size of the study was calculated based on pH and HCO

3

-

at the end of the surgery as the primary endpoints. Based on a pilot study with 6 cases in each group, the expected mean pH and HCO

3

-

were 7.35 ± 0.04 and 23.6 ± 2.4 mmol L

-1

in the propofol group; 7.40 ± 0.04 and 25.2 ± 1.6 mmol L

-1

in the sevoflurane group. For a power of 0.8 and α = 0.05, based on the formula estimating sample size for comparison of two means

25

, a sample size of at least 17 patients in each group was calculated to be appropriate.

In the descriptive tables, quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) where applicable and were compared by the Student’s

Results

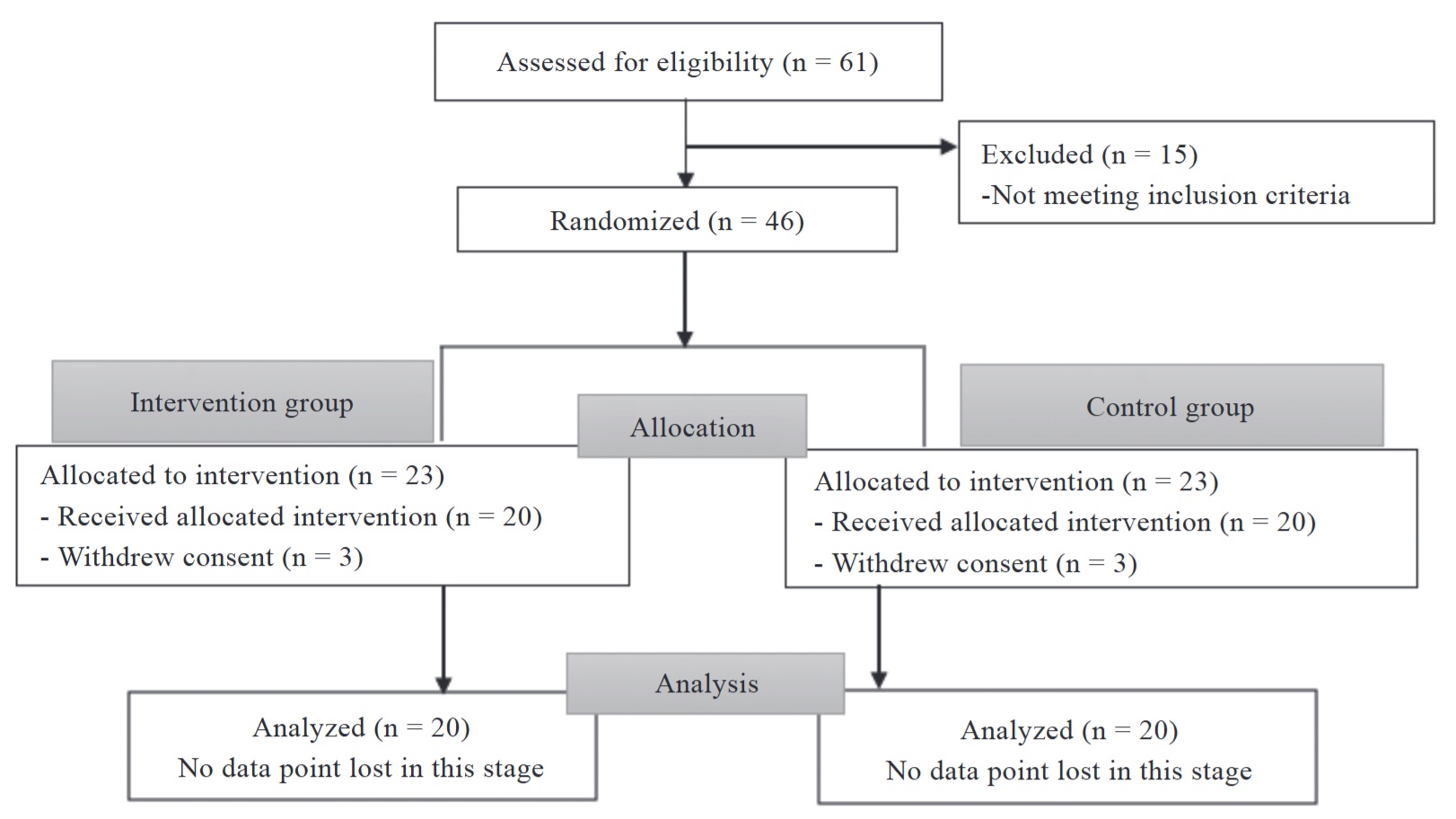

The study was conducted in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines. 26,27 A total of 46 patients were randomized. Six people were excluded because they withdrew consent. Of the remaining 40 patients, 20 had been allocated to the propofol group (intervention group) and 20 to the sevoflurane group (control group). The flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of the two groups were similar (Table 1). No significant differences were seen between groups in any of the preoperative and intraoperative patient characteristics.

Download full-size image

|

Patient characteristic |

Propofol (n = 20) |

Sevoflurane (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Preoperative data |

|||

|

Age (year) |

46.7 ± 13.8 |

46.2 ± 10.2 |

0.907 b |

|

Sex (M/F) |

10/10 |

8/12 |

0.525 c |

|

Weight (kg) |

53.6 ± 8.3 |

51.8 ± 6.0 |

0.448 b |

|

Height (cm) |

162.6 ± 7.4 |

160.4 ± 5.1 |

0.289 b |

|

BMI (kg/m 2 ) |

20.2 ± 2.1 |

20.1 ± 2.1 |

0.935 b |

|

ASA class (II/III/IV) |

9/11/0 |

4/15/1 |

0.176 e |

|

NYHA (I/II/III) |

0/16/4 |

2/12/6 |

0.260 e |

|

EF (%) |

63.4 ± 6.9 |

63.9 ± 11.5 |

0.869 b |

|

SPAP (mmHg), median (IQR) |

42.0 (36.0) |

43.0 (21.0) |

0.839 d |

|

EuroSCORE II |

1.3 ± 0.5 |

1.4 ± 0.6 |

0.448 b |

|

COPD, n (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

|

Diabetes, n (%) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (5.0) |

1.000 e |

|

Hypertension, n (%) |

2 (10.0) |

3 (15.0) |

1.000 e |

|

Type of surgery, n (%) |

|||

|

Replacement/repair of the mitral valve |

11 (55.0) |

8 (40.0) |

0.342 c |

|

Replacement of the aortic valve |

1 (5.0) |

2 (10.0) |

1.000 e |

|

Replacement/repair of the mitral valve and the aortic valve |

3 (15.0) |

4 (20.0) |

1.000 e |

|

Replacement/repair of the mitral valve and the tricuspid valve repair |

3 (15.0) |

4 (20.0) |

1.000 e |

|

Patching the atrial/ventricular septal defect |

2 (10.0) |

2 (10.0) |

1.000 e |

|

Intraoperative data |

|||

|

Midazolam (mg) |

2.0 ± 0.2 |

2.0 ± 0.1 |

0.330 b |

|

Fentanyl (mg) |

1.0 ± 0.3 |

0.9 ± 0.2 |

0.316 b |

|

Pipecuronium (mg) |

8.4 ± 1.4 |

8.3 ± 1.2 |

0.714 b |

|

Hematocrit (%) |

|||

|

Baseline |

42.9 ± 4.2 |

43.1 ± 3.5 |

0.890 b |

|

Lowest |

25.5 ± 3.7 |

26.6 ± 4.2 |

0.364 b |

|

Transfused blood product |

|||

|

Transfused patients, n (%) |

20 (100) |

19 (95.0) |

1.000 e |

|

PRC (mL) |

478 ± 265 |

465 ± 304 |

0.890 b |

|

FFP (mL) |

510 ± 152 |

490 ± 137 |

0.665 b |

|

Transfused crystalloid (mL) |

1,300 ± 441 |

1,125 ± 319 |

0.160 b |

|

Anesthesia time (min) |

238.0 ± 42.0 |

244.3 ± 41.1 |

0.637 b |

|

Operating time (min) |

199.5 ± 41.5 |

205.5 ± 39.4 |

0.639 b |

|

CPB time (min) |

100.2 ± 32.0 |

94.7 ± 35.7 |

0.611 b |

|

Aortic clamp time (min) |

77.0 ± 29.9 |

72.3 ± 30.1 |

0.627 b |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPB, cardio-

pulmonary bypass; EF, ejection fraction; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; F, female; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; IQR, interquartile range; M, male; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PRC, packed red cells; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

aData are presented as mean ± standard deviation, unless noted otherwise.

bStudent’s

cChi-squared

dMann–Whitney U

eFisher exact test.

Hemodynamic Stability

Heart rate, MAP, and central venous pressure were kept stable throughout the observation period. However, the MAP from the time after heart rate recovery until the end of surgery in the propofol group was lower than those in the sevoflurane group (70 ± 6 mmHg, 74 ± 8 mmHg, and 80 ± 6 mmHg in the propofol group vs. 75 ± 7 mmHg, 81 ± 6 mmHg, and 84 ± 5 mmHg in the sevoflurane group with

|

Parameter |

Propofol (n = 20) |

Sevoflurane (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

HR (bpm) |

|||

|

Base |

84 ± 14 |

79 ± 14 |

0.276 |

|

After heart beat recovery |

69 ± 8 |

72 ± 12 |

0.408 |

|

End of CPB |

76 ± 15 |

78 ± 10 |

0.563 |

|

End of surgery |

83 ± 17 |

84 ± 10 |

0.865 |

|

MAP (mmHg) |

|||

|

Base |

85 ± 13 |

85 ± 12 |

0.980 |

|

After heart beat recovery |

70 ± 6 |

75 ± 7 |

0.025 b |

|

End of CPB |

74 ± 8 |

81 ± 6 |

0.004 b |

|

End of surgery |

80 ± 6 |

84 ± 5 |

0.040 b |

|

CVP (mmHg) |

|||

|

Base |

6 ± 2 |

6 ± 2 |

0.600 |

|

After heart beat recovery |

10 ± 2 |

9 ± 3 |

0.052 |

|

End of CPB |

11 ± 1 |

10 ± 2 |

0.185 |

|

End of surgery |

10 ± 2 |

10 ± 2 |

0.660 |

|

CI (L min -1 m -2 ) |

|||

|

Base |

2.6 ± 0.8 |

2.6 ± 0.7 |

0.966 |

|

After heart beat recovery |

2.4 ± 0.5 |

2.6 ± 0.5 |

0.266 |

|

End of CPB |

2.5 ± 0.6 |

2.7 ± 0.5 |

0.149 |

|

End of surgery |

2.6 ± 0.6 |

2.9 ± 0.6 |

0.046 b |

The need for inotropic agents with dobutamine and vasopressors with noradrenaline during the study period was not significantly different between the two groups (35.0% and 65.0% in the propofol group vs. 20.0% and 40.0% in the sevoflurane group with

Primary Endpoint

There were no differences between groups in mean arterial blood pH, P

a

CO

2

and BE during the observation period. However, the incidence of metabolic acidosis with high lactate at the end of surgery was significantly higher in the propofol group (intervention group) than in the sevoflurane group (control group) (50.0% in the propofol group vs. 20.0% in the sevoflurane group with

|

Variable |

Propofol (n = 20) |

Sevoflurane (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Base |

|||

|

pH |

7.39 ± 0.03 |

7.39 ± 0.04 |

0.967 b |

|

P a CO 2 (mmHg) |

44.3 ± 7.9 |

45.8 ± 5.3 |

0.487 b |

|

HCO 3 - (mmol L -1 ) |

26.5 ± 4.5 |

27.3 ± 2.7 |

0.503 b |

|

BE (mmol L -1 ) |

1.4 ± 4.6 |

2.2 ± 3.0 |

0.532 b |

|

Lactate (mmol L -1 ) |

1.9 ± 1.4 |

2.0 ± 1.0 |

0.814 b |

|

Potassium (mmol L -1 ) |

3.6 ± 0.5 |

3.6 ± 0.5 |

0.747 b |

|

Metabolic acidosis, n (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

|

5 minutes after heart beat recovery |

|||

|

pH |

7.43 ± 0.07 |

7.44 ± 0.06 |

0.536 b |

|

P a CO 2 (mmHg) |

39.0 ± 7.6 |

38.5 ± 5.0 |

0.827 b |

|

HCO 3 - (mmol L -1 ) |

25.6 ± 2.1 |

26.3 ± 1.8 |

0.288 b |

|

BE (mmol L -1 ) |

1.3 ± 2.5 |

2.2 ± 2.2 |

0.255 b |

|

Lactate (mmol L -1 ) |

2.9 ± 1.1 |

2.6 ± 0.8 |

0.455 b |

|

Potassium (mmol L -1 ) |

4.6 ± 0.5 |

4.6 ± 0.7 |

0.817 b |

|

Metabolic acidosis, n (%) |

1 (5.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1.000 c |

|

End of CPB |

|||

|

pH |

7.37 ± 0.08 |

7.36 ± 0.06 |

0.767 b |

|

P a CO 2 (mmHg) |

40.5 ± 8.0 |

43.3 ± 7.3 |

0.264 b |

|

HCO 3 - (mmol L -1 ) |

23.0 ± 1.9 |

24.6 ± 4.1 |

0.124 b |

|

BE (mmol L -1 ) |

–2.3 ± 2.0 |

–0.8 ± 4.6 |

0.193 b |

|

Lactate (mmol L -1 ) |

4.2 ± 1.3 |

3.7 ± 1.4 |

0.244 b |

|

Potassium (mmol L -1 ) |

4.0 ± 0.5 |

4.0 ± 0.6 |

0.859 b |

|

Metabolic acidosis, n (%) |

8 (40.0) |

9 (45.0) |

0.749 d |

|

End of surgery |

|||

|

pH |

7.37 ± 0.07 |

7.38 ± 0.07 |

0.491 b |

|

P a CO 2 (mmHg) |

40.4 ± 5.7 |

42.7 ± 7.3 |

0.274 b |

|

HCO 3 - (mmol L -1 ) |

23.2 ± 3.0 |

25.2 ± 3.0 |

0.042 b,e |

|

BE (mmol L -1 ) |

–2.1 ± 3.7 |

0.1 ± 3.4 |

0.053 b |

|

Lactate (mmol L -1 ) |

5.4 ± 1.9 |

4.3 ± 1.5 |

0.042 b,e |

|

Potassium (mmol L -1 ) |

4.1 ± 0.5 |

4.1 ± 0.6 |

0.747 b |

|

Metabolic acidosis, n (%) |

10 (50.0) |

4 (20.0) |

0.047 d,f |

Abbreviations: BE, base excess; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass.

aData are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

bStudent’s t-test.

cFisher exact test.

dChi-squared test.

eP < 0.05 compared with the sevoflurane group obtained with Student’s t-test.

fP < 0.05 compared with the sevoflurane group obtained with Chi-squared test.

Secondary Endpoints

The average serum levels of AST, ALT, urea, and creatinine, as well as the proportions of patients with increased liver enzymes and kidney damage before and at the end of surgery in the two groups, were not statistically different with

|

Variable |

Propofol (n = 20) |

Sevoflurane (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Before surgery |

|||

|

AST (U L -1 ) |

29.7 ± 11.1 |

31.5 ± 10.7 |

0.594 b |

|

ALT (U L -1 ) |

31.4 ± 18.2 |

30.8 ± 16.1 |

0.912 b |

|

Elevated transaminases, n (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

|

Urea (mmol L -1 ) |

6.1 ± 1.9 |

6.1 ± 1.6 |

0.982 b |

|

Creatinine (µmol L -1 ) |

76.0 ± 20.6 |

69.7 ± 16.0 |

0.291 b |

|

Renal injury, n (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

|

End of surgery |

|||

|

AST (U L -1 ) |

93.1 ± 58.1 |

77.6 ± 37.1 |

0.321 b |

|

ALT (U L -1 ) |

37.9 ± 19.7 |

40.1 ± 42.4 |

0.831 b |

|

Elevated transaminases, n (%) |

8 (40.0) |

7 (35.0) |

0.744 c |

|

Urea (mmol L -1 ) |

6.4 ± 1.6 |

6.2 ± 1.5 |

0.715 b |

|

Creatinine (µmol L -1 ) |

86.7 ± 22.2 |

84.9 ± 24.8 |

0.810 b |

|

Renal injury, n (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; NA, not available.

aData are presented as mean ± standard deviation, unless noted otherwise.

bStudent’s

cChi-squared

The proportion of patients with persistent bradycardia during surgery was 0.0% in the propofol group and 10.0% in the sevoflurane group (

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that the use of propofol during the entire anesthesia process was associated with metabolic acidosis in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, as demonstrated by the incidence of metabolic acidosis and mean lactate levels in plasma at the end of surgery in the propofol group were higher than those in the control group (sevoflurane group). Many factors influence metabolic acidosis in cardiac surgery patients with CPB. Among these, characteristics of study patients, surgery, CPB, and anesthesia, as well as other surgery-related events, such as decreased oxygen delivery due to hypovolemia, hypotension, and/or anemia during surgery, etc., are the most common causes. In this study, the characteristics of study patients, surgery, and CPB of the two study groups were similar. In addition, the rate of patients requiring blood transfusion as well as the average amount of transfused blood during surgery between the two groups was not statistically different. On the other hand, the proportion of patients with hypotension who had to use noradrenaline to raise blood pressure, as well as the use of inotropic support with dobutamine in the two groups, was also not significantly different. Particularly, the MAP from the time after heart rate recovery (after aortic unclamping) to the end of surgery as well as the cardiac index at the end of surgery in the propofol group were lower than those in the sevoflurane group, but these differences were not considered clinically significant because these blood pressure and cardiac index values still reached the treatment target (> 65 mmHg and ≥ 2.4 L min -1 m -2 , respectively). Thus, these characteristics of the two groups were similar, suggesting that the propofol group had a higher rate of metabolic acidosis at the end of surgery than the control group was not caused by differences in patient characteristics and surgery-related events but instead appears to be related to the choice of propofol.

Metabolic acidosis is the most important pathological sign of PRIS. Mechanisms leading to PRIS are unknown. Early theories about the cause of acidosis in PRIS included impaired hepatic lactate metabolism caused by intralipid present in propofol, leading to lactate accumulation and acidosis. Recently, it has been proposed that the syndrome may be caused by either a direct mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibition or impaired mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism mediated by propofol. 28 In the context of cardiac surgery with CPB, the risk of PRIS may be heightened due to altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol during CPB. Hemodilution during CPB reduces plasma protein concentrations, leading to an increase in the unbound fraction of propofol. 29,30 This alteration can enhance the central nervous system depressant effects of propofol, potentially leading to further metabolic acidosis. Additionally, CPB-induced hypothermia and reduced hepatic and renal blood flow can impair the metabolism and clearance of propofol, further increasing its effects. 30

The results of our above study also agreed with the reports of Cravens et al. 20 in 2007 in patients undergoing noninvasive radiofrequency ablation for atrial Flutter or fibrillation. In this study, the authors found a significantly higher incidence of subclinical metabolic acidosis in patients receiving propofol infusion at a mean rate of approximately 50 μg kg -1 min -1 over a period of 4 to 10 hours compared to that in patients who did not receive propofol. However, our research results were different from the studies of some other authors. Research by Rozet et al. 21 in 2009 showed that in spine surgery patients, propofol anesthesia at doses of 8.8 ± 2 mg kg -1 h -1 (approximately to the target of 4 μg mL -1 after 1 hour or 4.5 μg mL -1 after 8 hours of anesthesia, if target control infusion was used) lasting > 8 hours was not associated with an increase in blood lactate. 21 In fact, lactate levels were significantly higher in patients receiving volatile anesthesia compared to the levels in those receiving propofol anesthesia. Furthermore, a study by Choi et al. 19 in 2014 indicated that in neurosurgical patients, the rate of metabolic acidosis in the group total anesthetized with propofol under target concentration control of 3.5–5.0 µg mL -1 (5–15 mg kg -1 h -1 ) over a period of 4 to 8 hours was similar to that in the group maintained with sevoflurane. We speculate that the reason for the differences in our study results with those of the above authors may be related to differences in study subjects, surgical types and procedures, drug administration methods between studies, etc. Furthermore, all three studies mentioned above by the above authors also have a limitation that they were retrospective in design, making it difficult to rule out other causes of metabolic acidosis in these patients. On the other hand, to the best of our knowledge, there has not been any specific study addressing this issue in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. Therefore, it is very meaningful for us to conduct this prospective study.

Metabolic acidosis is an early sign of PRIS that is related to the dose and duration of propofol infusion. PRIS was initially described in children receiving high-dose propofol infusions (> 4 mg kg -1 h -1 ) over long periods of time (> 48 h). 31 Subsequently, based on the data from case reports and case series, administering propofol for more than 48 hours was not recommended, nor was it recommended to administer a dose of more than 4 mg kg -1 h -1 (or 67 mcg kg -1 minute -1 ) because such doses and durations were potentially fatal. However, the report by Cravens et al. 20 suggested that metabolic acidosis may even develop immediately with subanesthetic doses of propofol commonly used for sedation. 21 For patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, a case report by Laquay et al. 24 in two pediatric patients aged 12 and 16 years undergoing mitral valve surgery showed that metabolic acidosis with elevated lactate occurred after 8-hour and 15-hour infusions of propofol at doses < 3 mg kg -1 h -1 . While in an adult patient undergoing coronary artery surgery, according to Ilyas et al. 23 , propofol infusions at larger doses up to 5.2 mg kg -1 h -1 resulted in metabolic acidosis with elevated lactate after only 1.5 hours. In our study design, in the propofol group, propofol was given a TCI at 1.5 μg mL -1 at the start, increased 0.5 μg mL -1 every two minutes, and then maintained 3–4 mcg mL -1 during the entire anesthetic process. Metabolic acidosis occurred mainly 2 to 5 hours after propofol infusion. The results of our study were also consistent with the majority of case reports. 21,22

Thus, caution should be exercised when using propofol because it is a dose and duration-sensitive drug, especially in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB who have preexisting myocardial injury and potential hemodynamic instability. Propofol dosage should be kept as low as possible and within the therapeutic range. The dose and duration of propofol use should be kept as low as possible and within the recommended range. Prompt discontinuation of propofol infusion at the first sign of metabolic acidosis can result in rapid improvement and may prevent progression to more severe manifestations of PRIS. Furthermore, clinicians should not use propofol in patients with known or suspected inborn errors of mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism. Alternative anesthetics may be considered in high-risk patients. Vigilant monitoring of arterial blood gases, lactate levels, and other metabolic parameters is essential in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, especially those receiving high-dose propofol infusions.

In addition to metabolic acidosis with hyperlactatemia, other signs of PRIS that may be seen are rhabdomyolysis, increased liver enzymes, kidney damage, and arrhythmia (widening of QRS complex, Brugada syndrome-like patterns, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, asystole) 9,10,32 . In this study, mean serum AST, ALT, urea, and creatinine levels, and the proportion of patients with increased liver enzymes and kidney damage at the end of surgery, as well as the proportion of patients with arrhythmia during surgery in the propofol group (intervention group) were not significantly different when compared with the control group. The results of our study also agreed with the case reports of Laquay et al. 24 in pediatric patients undergoing mitral valve surgery, as well as those of Ilyas et al. 23 in adult patients undergoing coronary artery surgery with CPB. These reports showed that, in addition to metabolic acidosis with elevated lactate, other signs of PRIS, such as increased liver enzymes, kidney dysfunction, and arrhythmia, did not appear. 23,24 However, we need further studies with larger sample sizes than case reports to clarify this issue.

We do acknowledge limitations to this study, and these limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. The first limitation of our study lies in the fact that this was a single-center study, as single-center studies may be influenced by the unique characteristics of a single study institution and may limit the generalizability of the study results. Additionally, although patients were randomly assigned to each study group, the anesthesiologists who directly cared for the patients could not have been unaware of the anesthetic technique used in each group. This lack of blinding could introduce observer bias, which could potentially influence the results and reduce the validity of our study. Nevertheless, the surgeon, cardiologist, other medical staff, and especially the clinical data manager were blind to group allocation, which would help minimize bias in the assessment of the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, total anesthesia with propofol was associated with metabolic acidosis but did not significantly affect increased liver enzymes, kidney damage, and arrhythmias when compared with the control group.

References

| 1 |

Krzych LJ, Szurlej D, Bochenek A.

Rationale for propofol use in cardiac surgery.

J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23(6):878-885.

Crossref |

| 2 |

Bonanni A, Signori A, Alicino C, et al.

Volatile anesthetics versus propofol for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: meta-analysis of randomized trials.

Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1429-1446.

Crossref |

| 3 |

Li F, Yuan Y.

Meta-analysis of the cardioprotective effect of sevoflurane versus propofol during cardiac surgery.

BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:128.

Crossref |

| 4 |

Jakobsen CJ, Berg H, Hindsholm KB, Faddy N, Sloth E.

The influence of propofol versus sevoflurane anesthesia on outcome in 10,535 cardiac surgical procedures.

J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21(5):664-671.

Crossref |

| 5 |

Vasile B, Rasulo F, Candiani A, Latronico N.

The pathophysiology of propofol infusion syndrome: a simple name for a complex syndrome.

Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(9):1417-1425.

Crossref |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

Hemphill S, McMenamin L, Bellamy MC, Hopkins PM.

Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured literature review and analysis of published case reports.

Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(4):448-459.

Crossref |

| 8 |

Rosen DJ, Nicoara A, Koshy N, Wedderburn RV.

Too much of a good thing? Tracing the history of the propofol infusion syndrome.

J Trauma. 2007;63(2):443-447.

Crossref |

| 9 |

Singh A, Anjankar AP.

Propofol-related infusion syndrome: a clinical review.

Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30383.

Crossref |

| 10 |

Mirrakhimov AE, Voore P, Halytskyy O, Khan M, Ali AM.

Propofol infusion syndrome in adults: a clinical update.

Crit Care Res Pract. 2015;2015:260385.

Crossref |

| 11 |

Mehta N, DeMunter C, Habibi P, Nadel S, Britto J.

Short-term propofol infusions in children.

Lancet. 1999;354(9181):866-867.

Crossref |

| 12 |

Liolios A, Guérit JM, Scholtes JL, Raftopoulos C, Hantson P.

Propofol infusion syndrome associated with short-term large-dose infusion during surgical anesthesia in an adult.

Anesth Analg. 2005;100(6):1804-1806.

Crossref |

| 13 |

Burow BK, Johnson ME, Packer DL.

Metabolic acidosis associated with propofol in the absence of other causative factors.

Anesthesiology. 2004;101(1):239-241.

Crossref |

| 14 |

Salengros JC, Velghe-Lenelle CE, Bollens R, Engelman E, Barvais L.

Lactic acidosis during propofol-remifentanil anesthesia in an adult.

Anesthesiology. 2004;101(1):241-243.

Crossref |

| 15 |

Hanna JP, Ramundo ML.

Rhabdomyolysis and hypoxia associated with prolonged propofol infusion in children.

Neurology. 1998;50(1):301-303.

Crossref |

| 16 |

Merz TM, Regli B, Rothen HU, Felleiter P.

Propofol infusion syndrome—a fatal case at a low infusion rate.

Anesth Analg. 2006;103(4):1050.

Crossref |

| 17 |

Fodale V, La Monaca E.

Propofol infusion syndrome: an overview of a perplexing disease.

Drug Saf. 2008;31(4):293-303.

Crossref |

| 18 |

Wysowski DK, Pollock ML.

Reports of death with use of propofol (Diprivan) for nonprocedural (long-term) sedation and literature review.

Anesthesiology. 2006;105(5):1047-1051.

Crossref |

| 19 |

Choi YJ, Kim MC, Lim YJ, Yoon SZ, Yoon SM, Yoon HR.

Propofol infusion associated metabolic acidosis in patients undergoing neurosurgical anesthesia: a retrospective study.

J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;56(2):135-140.

Crossref |

| 20 |

Cravens GT, Packer DL, Johnson ME.

Incidence of propofol infusion syndrome during noninvasive radiofrequency ablation for atrial flutter or fibrillation.

Anesthesiology. 2007;106(6):1134-1138.

Crossref |

| 21 |

Rozet I, Tontisirin N, Vavilala MS, Treggiari MM, Lee LA, Lam AM.

Prolonged propofol anesthesia is not associated with an increase in blood lactate.

Anesth Analg. 2009;109(4):1105-1110.

Crossref |

| 22 |

Krajčová A, Waldauf P, Anděl M, Duška F.

Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured review of experimental studies and 153 published case reports.

Crit Care. 2015;19:398.

Crossref |

| 23 |

Ilyas MIM, Balacumaraswami L, Palin C, Ratnatunga C.

Propofol infusion syndrome in adult cardiac surgery.

Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(1):e1-3.

Crossref |

| 24 |

Laquay N, Pouard P, Silicani MA, Vaccaroni L, Orliaguet G.

Early stages of propofol infusion syndrome in paediatric cardiac surgery: two cases in adolescent girls.

Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(6):880-881.

Crossref |

| 25 |

Chan YH.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)—sample size: the magic number?

Singapore Med J. 2003;44(4):172-174.

|

| 26 |

Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11(11):MR000030.

Crossref |

| 27 |

Sporbeck B, Jacobs A, Hartmann V, Nast A.

Methodological standards in medical reporting.

J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(2):107-120.

Crossref |

| 28 | |

| 29 |

Takizawa E, Hiraoka H, Takizawa D, Goto F.

Changes in the effect of propofol in response to altered plasma protein binding during normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass.

Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(2):179-185.

Crossref |

| 30 |

Barbosa RAG, Santos SRCJ, White PF, et al.

Effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on propofol pharmacokinetics and bispectral index during coronary surgery.

Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(3):215-221.

Crossref |

| 31 |

Michel-Macías C, Morales-Barquet DA, Reyes-Palomino AM, Machuca-Vaca JA, Orozco-Guillén A.

Single dose of propofol causing propofol infusion syndrome in a newborn.

Oxf Med Case Reports. 2018;2018(6):omy023.

Crossref |

| 32 |

Li WK, Chen XJC, Altshuler D, et al.

The incidence of propofol infusion syndrome in critically-ill patients.

J Crit Care. 2022;71:154098.

Crossref |