Abstract

Background

The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine the effect of surgical operation, age at surgery, sex hormones, and anesthesia modality on the risk of dementia in both sexes.

Methods

Data of females aged between 30 and 70 years old who were diagnosed with dysmenorrhea and underwent hysterectomy/myomectomy or without surgery, and males with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) with or without transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) were identified from the National Health Insurance Research Database 2000–2016. The effect of age at surgery, surgery type, and anesthesia modality on dementia risk was assessed using Cox regression analyses.

Results

Among the 855,893 subjects, 10,242 developed dementia. Surgery at older age increased dementia risk in both sexes. Among females, hysterectomy/myomectomy was not significantly associated with dementia risk , although myomectomy was associated with a lower risk for dementia than hysterectomy. In males, TURP significantly increased the risk of dementia.

Conclusion

Men with BPH and women with dysmenorrhea who were older at surgery have a higher risk of dementia. Regardless of the anesthetic method, surgery increased the risk of dementia in men. Among the data of women, although the surgery factor was not significantly associated with dementia risk, women with myomectomy had a lower risk of dementia than the ones with hysterectomy. These findings together contributed to risk stratification for each sex in such surgical settings.

Keywords

anesthesia, dementia, hysterectomy, myomectomy, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

Introduction

Males and females exhibited different risks of the occurrence of dementia although not fully understood. Women were more prone to have mental declines than men before having dementia diagnosis. More women than men were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and this may not be solely attributable to increased longevity. From previous studies, sex steroid hormones were the potential central modulators that underlie such risk discrepancy. 1 In the last decades, some research suggested that surgical menopause (also, oophorectomy) was independently associated with greater subsequent dementia risk or cognitive impairments. 2,3 However, other research suggested that hysterectomies during midlife were also associated with greater subsequent dementia risk or cognitive impairments. 4 It might be explained by shortened reproductive span as well as reduced cumulative exposure to estrogen. In our cross-sectional study conducted in 2019, we examined the cognitive dysfunction after operation in perimenopausal women and found that the duration of menopause was independently associated with impaired postoperative cognition. 5 In another study by our research team, a 14-year longitudinal risk assessment of dementia after hysterectomies was performed, and it was found that not only age at hysterectomy but also the modality of anesthesia significantly correlates with dementia risk. Specifically, general anesthesia (GA) was associated with higher dementia risk as compared with spinal anesthesia (SA), along with a greater impact observed in younger females. 6 The results of the above-cited study further joined the recent debates in the medical literature on whether exposure to GA increased the incidence of dementia. 7-9 Nevertheless, it was indicated that age at surgery, cumulative exposure to female sex hormones, and anesthesia modality in gynecological surgery all had an impact on short-term and long-term cognition, and it further warranted the need for investigating their potential interactions.

Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) was common in elderly men, occurring in 15% to 60% of men aged more than 40 years and increasing markedly with age. 10,11 Current therapies can be divided into conservative or surgical interventions, of which transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) has long been considered the historical gold standard for the surgical treatment of BPH and has been recognized as the second most commonly performed operation in the United States previously. 12,13 Despite the fact that medical treatment for BPH has been questioned for its potential adverse effects on individual mental disorders, including dementia and depression 14,15 , no prior study has reported any association between TURP and subsequent psychiatric problems. Consequently, we deemed that it would be informative to include males with BPH for the sake of assessing the relationships between anesthesia modality and the risk of dementia accompanying women undergoing hysterectomies.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate the potential interaction between procedures, age at surgery, sex hormones, and modality of anesthesia on the risk of dementia in both sexes. We retrospectively compared the females who received hysterectomy versus myomectomy, a procedure without removal of the uterus, for the incidence of dementia at follow-up. We also assessed the impact of TURP and the anesthesia modality on the risk of dementia in males. The influence of age at such surgeries on dementia risk was evaluated among men and women. The analyses were conducted at a population level, using Taiwan’s nationally representative insurance database.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

The detailed study design is depicted in Supplementary Figure S1. This was an observational, retrospective cohort study using the data of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from 2000 to 2016. In this database, we excluded females aged between 30 and 70 years old who were diagnosed with dysmenorrhea, and males aged between 30 and 70 years old who were diagnosed with BPH with or without TURP. Females and males with missing data of the main study variables or duplicated surgical records were excluded from the primary cohort. Patients with a history of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, stroke, or brain surgery before the date of the first diagnosis of dysmenorrhea or BPH were also excluded. Information of age at surgery, type of surgery including myomectomy or hysterectomy in females, and modality of anesthesia (i.e., GA, SA, and epidural anesthesia [EA]) in both males and females were also extracted and included in the subsequent analyses (Supplementary Figure S1).

Ethical Statement

The data were obtained from the Health and Welfare Database of the Ministry of Health and Welfare Collaboration Center of Health Information Application. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Far Eastern Hospital (No:106113-E). The requirement for informed consent was waived since this study was a secondary analysis of a public database in which all patients’ personal information was anonymized. The data files used for analysis followed those used in our previous study and described therein. 5

Study Variables

The primary endpoint of the present analysis was the risk of incident dementia at follow-up. The diseases and procedures in the analyses were identified according to the ninth (ICD-9-CM) and tenth editions (ICD-10-CM) of the International Classification of Diseases from the outpatient and inpatient list files of the database. The codes utilized are listed below:

Dementia:

• Other cerebral degenerations: ICD-9-CM: 331; ICD-10-CM: G300/G301/G308/G309/G311

• Senile and presenile organic psychotic conditions: ICD-9-CM: 290; ICD-10-CM: F0390

• Dementia in conditions classified elsewhere: ICD-9-CM: 294.1; ICD-10-CM: F0280/F0281

Only cases with inpatient visits and two or more outpatient visits with the above diagnostic codes were included, and those with dementia diagnosed within three months after hysterectomy/myomectomy or TURP have been excluded. We have also excluded patients with a medical history as described below (only ICD-9-CM before 2011 in Taiwan):

• Cancer: ICD-9-CM:140-208

• Parkinsonism: ICD-9-CM: 332;

• Stroke: ICD-9-CM: 430-434

• Brain operations: ICD-9 procedure codes 01-04

Type of Surgery

The following surgical procedures were further identified by procedure claim codes listed below:

• Hysterectomy: 80403B, 80404C, 80421B, 80416B

• Myomectomy: 80402C, 80420C, 80425C

• TURP: 79406B, 79413B, 79414B, 79415B, N20002

Modality of Anesthesia

We distinguished only two ways of anesthesia using the following codes:

• GA: 96020C

• Regional anesthesia, including SA: 96007C, or EA: 96005C

Comorbidities

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), which accounts for 17 diseases, was used for patient characteristics analysis. 16,17

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were presented as n (%) and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Cox regression analyses were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the risk for developing dementia after hysterectomy, myomectomy, or TURP. The assumption of proportional hazards was checked. A two-sided

Results

A total of 855,893 male and female subjects aged between 30 and 70 years old were included between the years 2000 and 2016 in the database, of which 10,242 (1.2%) developed dementia at follow-up. Supplementary Table S1 shows the baseline characteristics of the entire study cohort with and without dementia. As compared with female subjects, a greater proportion of males had developed dementia (2.28% vs. 0.60%,

Supplementary Table S2 shows the baseline characteristics of the study cohort with and without dementia, stratified by gender. For females, the proportion of dementia was greater in patients who had received surgery than those who had not (0.63% vs. 0.57%,

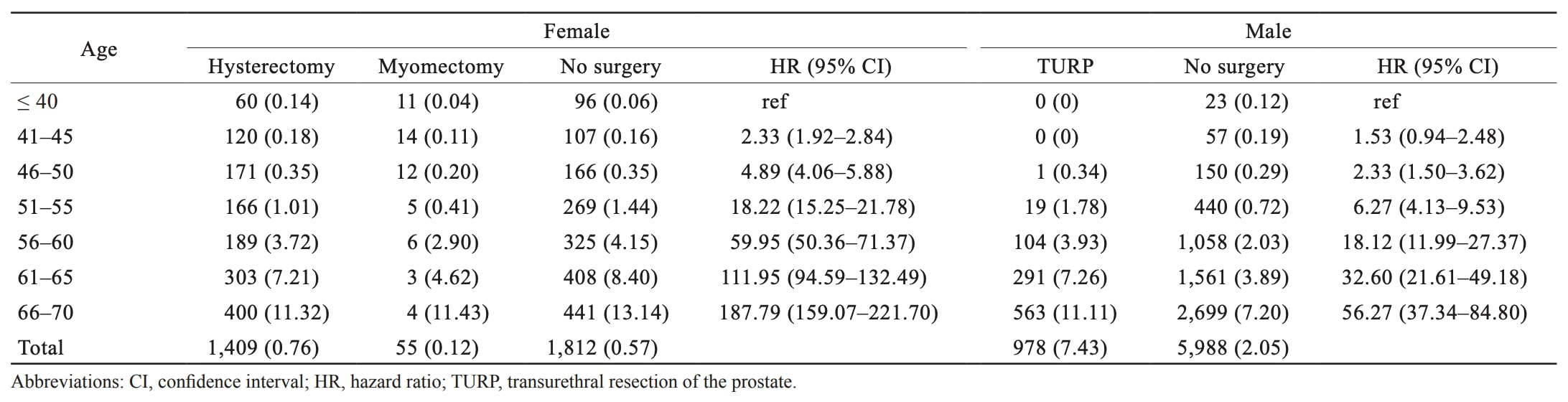

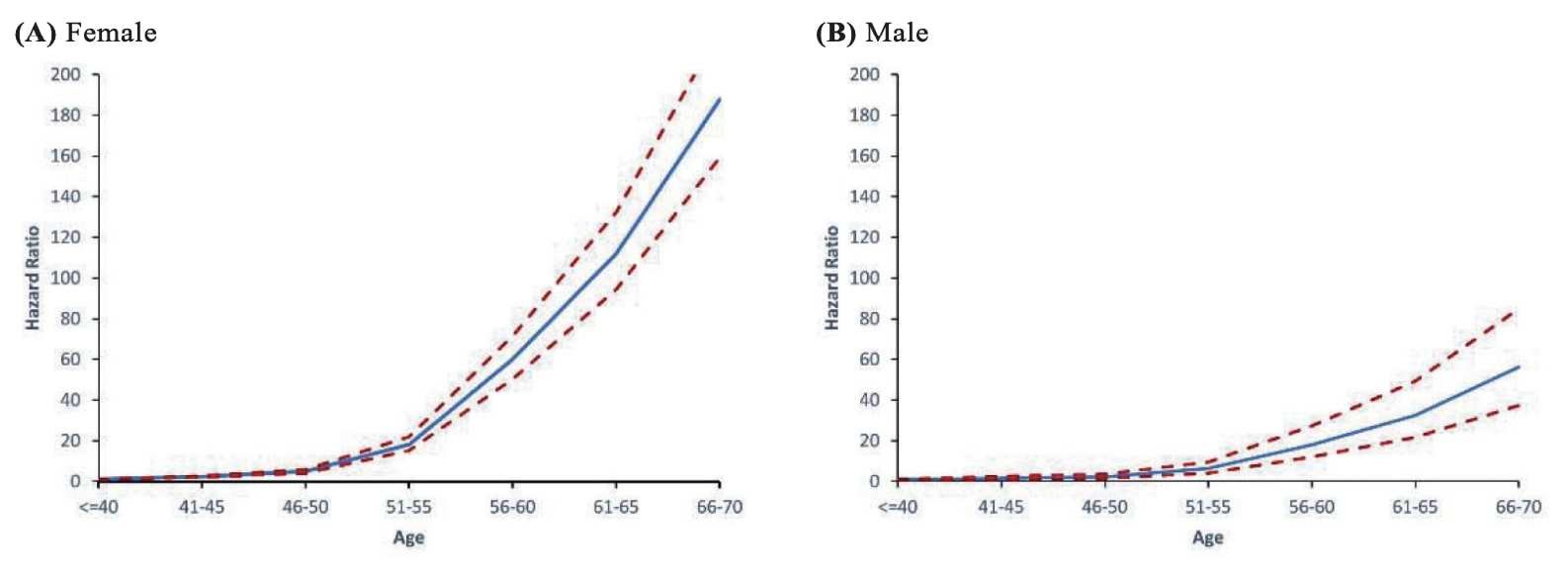

Table 1 shows the frequencies and risks of dementia by gender and surgical status at different ages. Both in males and females, as age increases, the HRs for dementia also rise. A substantial increase in the risk can be observed in females around 50 years old (HR = 59.96 in 56–60 years old; 18.22 in 51–55 years old). For males, this situation can be observed around 56 years of age (HR = 18.12 in 56–60 years old; 6.27 in 51–55 years old) (Table 1). The risk of dementia by gender at a different age is depicted in Figure 1.

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

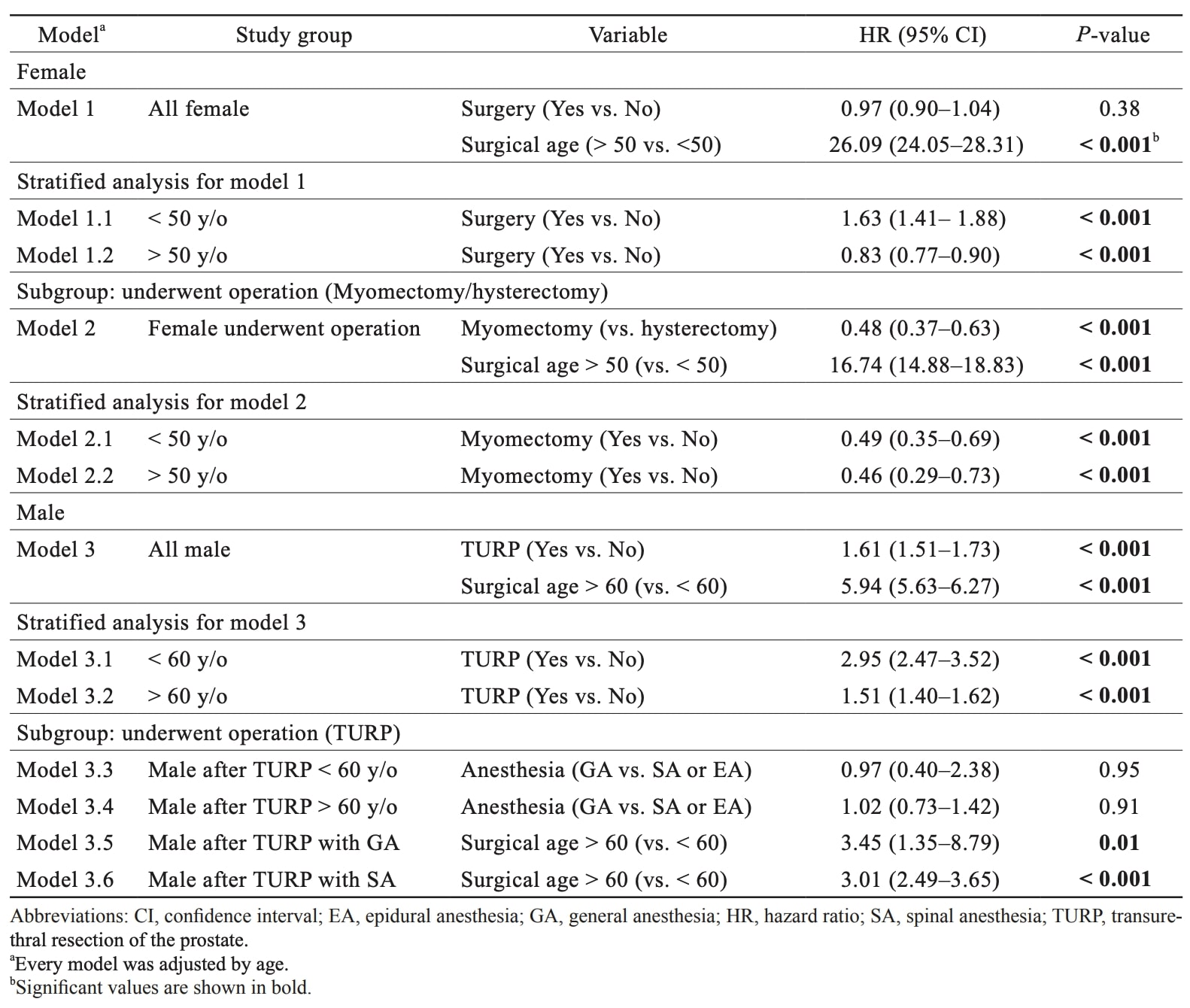

Table 2 shows the impact of surgery, age at surgery, and anesthesia on the risk for dementia. For all females with dysmenorrhea, surgical treatment with hysterectomy or myomectomy was not significantly associated with the risk for dementia (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.90–1.04;

surgery became significantly associated with increased risk for dementia in < 50 y/o subgroup (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.41–1.88;

Download full-size image

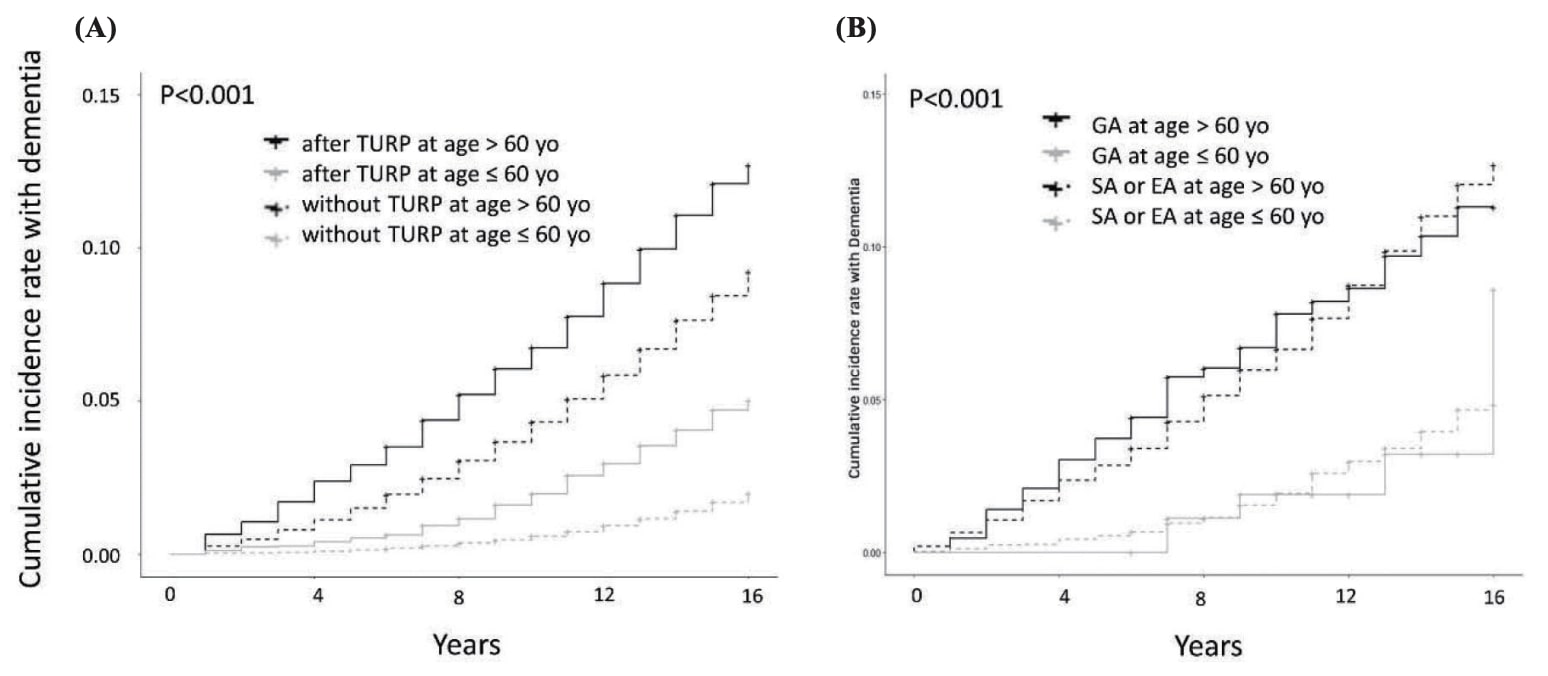

In males, TURP was significantly associated with an increased risk for dementia (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.51–1.73). In addition, age at surgery > 60 years old was also associated with a higher risk for dementia as compared with < 60 of age (HR, 5.94; 95% CI, 5.63–6.27). TURP significantly increases the risk for dementia in both ≤ 60 or > 60-year-old males. With regard to the modality of anesthesia, GA was not associated with a higher risk for dementia than SA/EA in either < 60 or > 60-year-old males (Table 2).

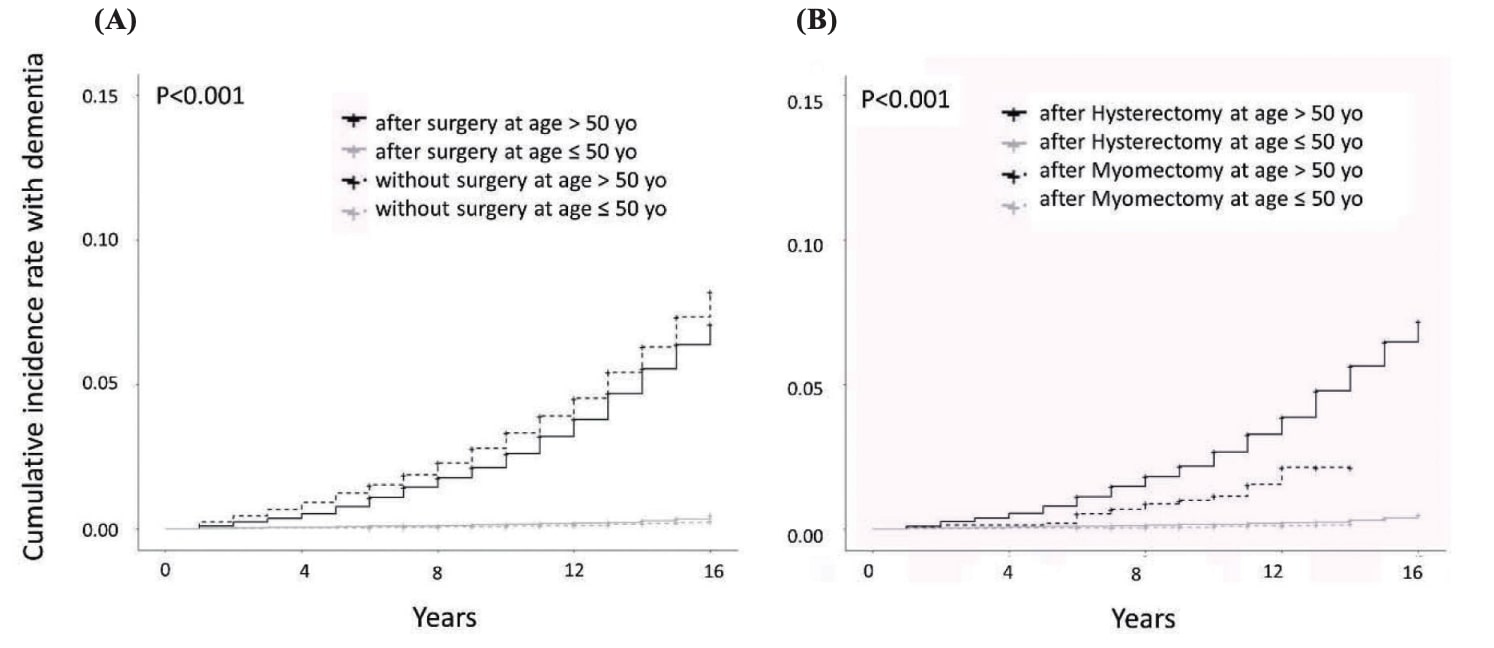

Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence of dementia in females with (A) surgery versus no surgery; (B) hysterectomy versus myomectomy, stratified by age. While stratifying females by age (≤ 50 years old or > 50 years old) and whether they had undergone surgery, it was observed that the cumulative incidence of dementia in females ≤ 50 years old did not increase significantly with age or whether they had undergone surgery. Therefore, there was almost no difference in the cumulative incidence of dementia between the two groups. However, whether females > 50 years old have undergone surgery, the cumulative incidence of dementia will increase with age. Among them, the cumulative incidence of dementia in the female who had not undergone surgery was significantly higher than that of the female who had undergone surgery. If we further divided the operation into hysterectomy and hysterectomy subgroups, it could be observed that the cumulative incidence of dementia would not increase with age in females ≤ 50 years old, no matter what kind of surgery was performed. However, whether females > 50 years old underwent hysterectomy or hysterectomy, the cumulative incidence of dementia would increase significantly with age. Females who underwent hysterectomy would increase faster with age than those who undergo myomectomy. The incidence of dementia in women who underwent hysterectomy was also significantly higher than that of women who underwent myomectomy (Figure 2).

Download full-size image

Figure 3 shows the cumulative incidences of dementia in males with (A) TURP versus no TURP; (B) GA versus SA/EA, stratified by different ages. The cumulative incidence of dementia increases with age. And, the cumulative incidence in descending order to four subgroups are always as follows: received TURP at age > 60 years old, non-received TURP at age > 60 years old, received TURP at age ≤ 60 years old, and non-received TURP at age > 60 years old. If we further divided TURP into GA and SA/EA subgroups, the pattern that the cumulative incidence of dementia increases with age could still be observed. The cumulative incidence of dementia of the first 12 years in the GA at the age > 60 years old subgroup was greater than the SA/EA at age > 60 years old subgroup, and the SA/EA at age > 60 years old subgroup will surpass the GA at age > 60 years old subgroup after 12 years. In addition, regardless of the GA or SA/EA subgroup, males > 60 years old had a significantly higher cumulative incidence of dementia than males ≤ 60 years old (Figure 3).

Download full-size image

Discussion

The interplay of age, surgery, sex hormones, and anesthesia modality had certain impacts on the risk of developing dementia among males and females. It was found that older age at surgery was significantly associated with increased dementia risk in both sexes. Moreover, after adjusting for age, women who received myomectomies posed a lower risk of dementia as compared with those who received hysterectomies, probably because of the longer duration of exposure to female sex hormones. On the other hand, TURP in males with BPH significantly increases the risk of dementia during later life. Modality of anesthesia in TURP did not significantly increase the risk of dementia either among < 60 or > 60-year-old males.

Men and women exhibit differences in the development and progression of AD. 1,2 A recent investigation into sex-specific pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD risk has suggested the menopause transition, a midlife neuroendocrine transition state unique to women. 18 Females with greater endocrine dyscrasia around menopause and males with andropause were more likely to develop cognitive loss and AD; thereby, circulating sex hormones may serve as surrogate biomarkers for cognitive decline. 19,20

In our previous population study, it was found that the risk of dementia did not increase linearly with age at total hysterectomy but showed an S-curve, with an exponential increase around 50 years of age. The findings indicate that factors including surgical triggers, anesthetic agents, and the duration of female hormone exposure may jointly contribute to the development of dementia under complicated interactions. 5

In the present analyses, women who received myomectomy had a significantly lower risk of dementia than those who received hysterectomy after adjustment. This result indirectly indicates that a longer duration of exposure to female hormones is a protective factor against later dementia, which is consistent with the findings reported by the previous studies. 3,4

For males, a previous meta-analysis reported that lower levels of testosterone might be associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia or AD. 21 However, another recent meta-analysis concluded only limited evidence can support the possible contribution of testosterone in the pathogenesis of the age-dependent impairment of cognitive functions. 22 The analyses of the present study did not focus on the effect of andropause on the risk of cognitive function; instead, males with BPH with or without resections for the prostate had been concentrated. It was known that men with BPH had persistently higher risk of AD and all-cause dementia compared with the general population, potentially mediated through sleep disturbance. 23 However, whether TURP attenuates the risk of dementia had never been evaluated yet. In the present study, the results showed that TURP significantly increased the risk of dementia either among males < 60 or > 60 years of age. However, anesthesia modality in TURP seemed not to correlate with dementia risk. Nonetheless, the underlying mechanism could not be answered based on the present study design. Future prospective studies with more confounders being included and adjusted are strongly recommended to address the relevant issues.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to assess the relationship between dementia and gynecological surgery in terms of myomectomy versus hysterectomy and accounting for age at surgery. This analysis was also the first to evaluate the links between anesthesia modalities in the setting of TURP for males. The major strength was the utilization of the NHIRD, which consists of subjects selected from a nationwide registry covering 99% of the 23 million people in Taiwan.

There are certain limitations associated with the current study design. First, the administrative codes are used to identify the endpoints and comorbidities in which coding errors may exist and thus hinder the reliability of the statistical analysis. Second, powerful confounders associated with socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors were not included and adjusted in the dataset. Third, data from NHIRD are suitable to use power analysis to deal with the cohort of a million sample size. This was a retrospective study with a lower level of evidence than prospective cohorts. In a prospective fashion, our future goal is to trace all dementia risk factors prior to the hysterectomy and prostate resection and follow up of all participants in long-term clinical settings.

Conclusion

In women who had received myomectomy or hysterectomy and men who received TURP, older age at surgery was substantially associated with increased dementia risk. After adjusting for age, women who received myomectomy had a lower risk of subsequent dementia than those who received hysterectomy. In addition, TURP significantly increased the risk of dementia in males with BPH. Further, the modality of anesthesia in TURP did not significantly influence the risk of dementia in males.

References

| 1 | |

| 2 |

Gilsanz P, Lee C, Corrada MM, Kawas CH, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA.

Reproductive period and risk of dementia in a diverse cohort of health care members.

Neurology. 2019;92(17):e2005-e2014.

|

| 3 |

Georgakis MK, Beskou-Kontou T, Theodoridis I, Skalkidou A, Petridou ET.

Surgical menopause in association with cognitive function and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;106:9-19.

|

| 4 |

Phung TKT, Waltoft BL, Laursen TM, et al.

Hysterectomy, oophorectomy and risk of dementia: a nationwide historical cohort study.

Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(1):43-50.

|

| 5 |

Chen YC, Sun WZ.

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction in premenopausal versus postmenopausal women.

Climacteric. 2020;23(2):165-172.

|

| 6 |

Chen YC, Oyang YJ, Lin TY, Sun WZ.

Risk assessment of dementia after hysterectomy: analysis of 14-year data from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan.

J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83(4):394-399.

|

| 7 |

Lee JJ, Choi GJ, Kang H, et al.

Relationship between surgery under general anesthesia and the development of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:3234013.

|

| 8 |

Kim CT, Myung W, Lewis M, et al.

Exposure to general anesthesia and risk of dementia: a nationwide population-based cohort study.

J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(1):395-405.

|

| 9 |

Velkers C, Berger M, Gill SS, et al.

Association between exposure to general versus regional anesthesia and risk of dementia in older adults.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):58-67.

|

| 10 |

Vuichoud C, Loughlin KR.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia: epidemiology, economics and evaluation.

Can J Urol. 2015;22 Suppl 1:1-6.

|

| 11 |

Lokeshwar SD, Harper BT, Webb E, et al.

Epidemiology and treatment modalities for the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8(5):529-539.

|

| 12 |

Young MJ, Elmussareh M, Morrison T, Wilson JR.

The changing practice of transurethral resection of the prostate.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100(4):326-329.

|

| 13 |

Wei JT, Calhoun E, Jacobsen SJ.

Urologic diseases in America project: benign prostatic hyperplasia.

J Urol. 2005;173(4):1256-1261.

|

| 14 |

Tae BS, Jeon BJ, Choi H, Cheon J, Park JY, Bae JH.

α-blocker and risk of dementia in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a nationwide population based study using the National Health Insurance Service Database.

J Urol. 2019;202(2):362-368.

|

| 15 |

Duan Y, Grady JJ, Albertsen PC, Helen Wu Z.

Tamsulosin and the risk of dementia in older men with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(3):340-348.

|

| 16 |

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA.

Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases.

J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

|

| 17 |

Chen PL, Yang CW, Tseng YK, et al.

Risk of dementia after anaesthesia and surgery.

Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):188-193.

|

| 18 |

Scheyer O, Rahman A, Hristov H, et al.

Female sex and Alzheimer’s risk: the menopause connection.

J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2018;5(4):225-230.

|

| 19 |

Hayashi K, Gonzales TK, Kapoor A, Ziegler TE, Meethal SV, Atwood CS.

Development of classification models for the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease utilizing circulating sex hormone ratios.

J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(3):1029-1046.

|

| 20 |

Atwood CS, Bowen RL.

The endocrine dyscrasia that accompanies menopause and andropause induces aberrant cell cycle signaling that triggers re-entry of post-mitotic neurons into the cell cycle, neurodysfunction, neurodegeneration and cognitive disease.

Horm Behav. 2015;76:63-80.

|

| 21 |

Zhang Z, Kang D, Li H.

Testosterone and cognitive impairment or dementia in middle-aged or aging males: causation and intervention, a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2021;34(5):405-417.

|

| 22 |

Corona G, Guaraldi F, Rastrelli G, Sforza A, Maggi M.

Testosterone deficiency and risk of cognitive disorders in aging males.

World J Mens Health. 2021;39(1):9-18.

|

| 23 |

Nørgaard M, Horváth-Puhó E, Corraini P, Sørensen HT, Henderson VW.

Sleep disruption and Alzheimer’s disease risk: inferences from men with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

EClinicalMedicine. 2021;32:100740.

|