Abstract

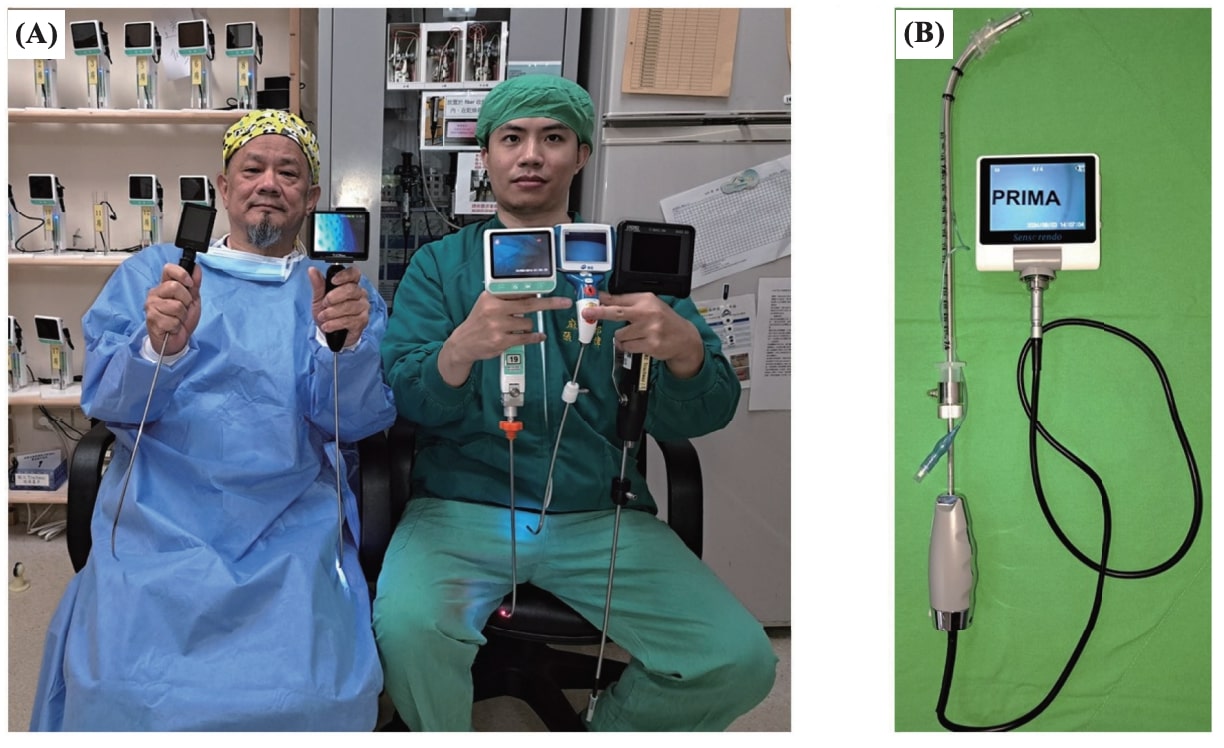

In contrast to direct laryngoscopy (DL) and video laryngoscopy (VL), the rigid video intubating stylet technique (styletubation) has recently been widely applied as a first-line airway management modality. 1-5 The advantages of using styletubation (Figure 1) for first-line and routine tracheal intubation include short intubating time, high first-pass success rate, no need for external laryngeal maneuvers or sniffing position, minor autonomic stimulation, negligible airway-related complications, astonishing airway operator’s self-satisfaction, and easy learning for the novice or inexperienced airway management learner. With our vast clinical experiences of using styletubation as the first-line intubating tool (more than 7,000 cases a year), we feel comfortable and trustable with this intubating technique.

Download full-size image

(A) Storz C-MAC ® video stylet, Tuoren Video Intubating System, UESCOPE ® video stylet, Clarus Video System (Trachway), Anestek Stylet-Go, and (B) Sensorendo Video Stylet.

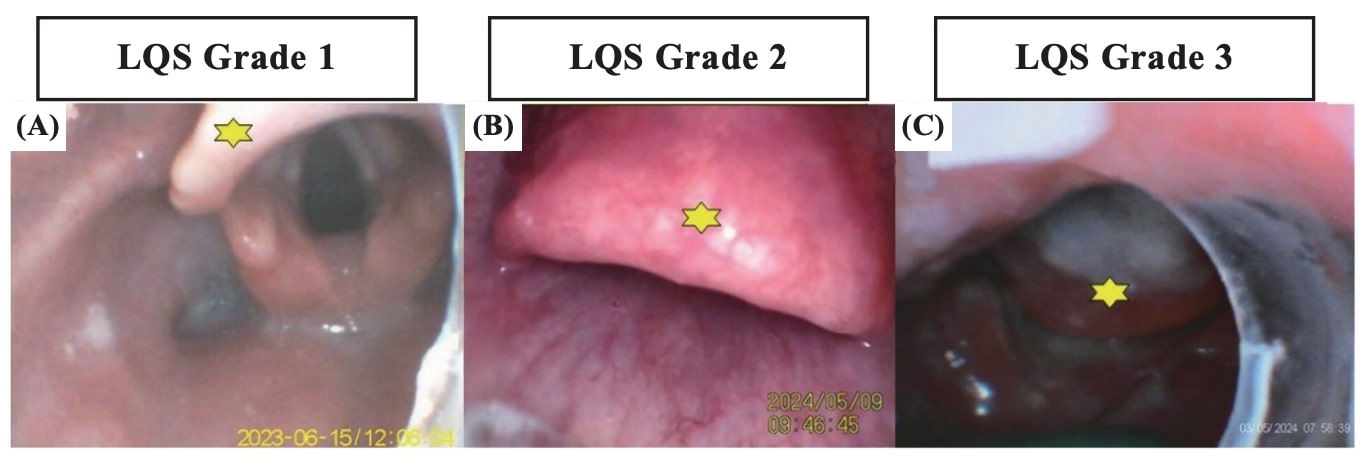

A difficult airway (DA) is conventionally defined as a clinical airway management situation in which unanticipated or anticipated “difficulty or failure” is experienced by a well-trained anesthetist, including applying facemask ventilation, laryngoscopy, supraglottic airways, tracheal intubation/extubation, or invasive airway. 6 The incidence of DA of styletubation, when it was structured as a routine application technique, is much lower than one might imagine. When the traditionally defined “predicted DA” cases (e.g., limited mouth opening, head/neck tumor, cervical spine immobility, obesity, etc.) were excluded, both the first-pass success rate and overall success rate for the styletubation were pretty high. While the predicted DA cases were included, the failed intubation rate for styletubation is 3 out of 55,000 cases (Luk, personal communication). Figure 2 shows three examples of the glottis visualization status during styletubation when an airway assistant performed jaw-thrust maneuver. The LQS (Luk-Qu-Shikani) grading system was applied and classified as Grade 1 (Figure 2A), Grade 2 (Figure 2B), and Grade 3 (Figure 2C), based on the exposure status and visualization of the glottis. The incidence of Grade 3 was relatively low and usually occurred in patients with predicted DA scenarios.

Download full-size image

(A) A 65-year-old woman (143 cm, 47 kg) underwent radiofrequency ablation of renal tumor. The glottic view was excellent under simple jaw-thrust. (B) An obese 46-year-old man (177 cm, 115 kg) underwent nasal septoplasty and rhinoplasty. The epiglottis could not be lifted up easily. (C) A 61-year-old man (167 cm, 48 kg) underwent total laryngectomy. Neck fibrosis due to concurrent chemoradiotherapy limited the neck mobility. The epiglottis was attached to the posterior pharyngeal wall. The yellow star labeled the epiglottis in each panel.

Several technical difficulties have been occasionally encountered when anesthetists applied styletubation for tracheal intubation. 7,8 Those difficulties, which caused subsequent failed attempts, include impediment of epiglottis and subsequent sub-optimal full-glottic visualization. The varying size, shape, and position of the epiglottis, in addition to other predicted difficulties by restricted mouth-opening, limited cervical spine mobility, severe obesity, oro-pharyngeal mass, etc., might obstruct the panoramic view of glottis opening (Figure 2). When the styletubation technique is applied for both routine and emergency tracheal intubation, it can be accomplished by a single airway operator (elevation of the patient’s jaw using the sole operator’s non-dominant big thumb) or with the help of an airway assistant (to conduct maneuver of mouth-opening and jaw-thrust on the patient). 2

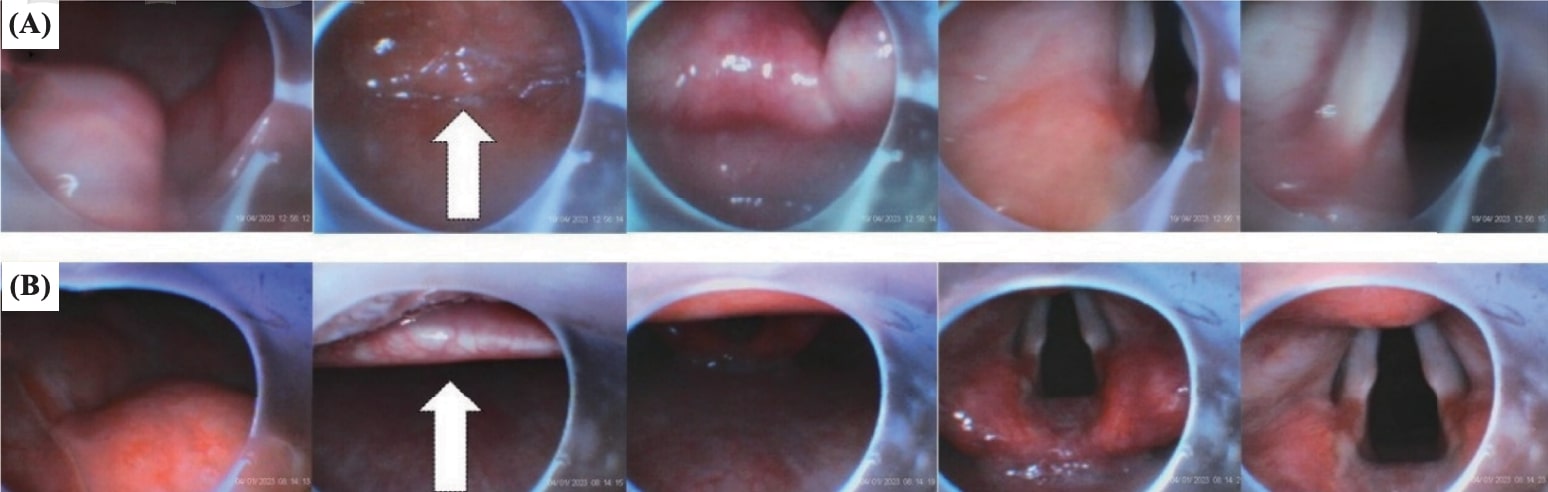

When the patient’s epiglottis status is categorized as LQS Grade 1, the styletubation can be easily and smoothly conducted by the midline approach. Namely, the operator simply advanced the stylet-endotracheal tube (stylet-ETT) assembly unit beneath the epiglottis and moved straightforwardly into the glottic opening area (Figure 3). In contrast to the LQS Grade 1 scenario, more cases are presented as LQS Grade 2 (Figure 4). In such a patient population, the space between the epiglottis and posterior pharyngeal wall could be narrow and no part of the vocal cords could be visualized. Under such inconvenient but not impossible conditions, one can manipulate the stylet either by simple midline approach underneath the epiglottis or by lateral approach. The latter technique involved a sweeping of the stylet-tube assembly from the lateral side of the epiglottis, then moving back to the midline underneath the epiglottis, and the glottis view can be acquired (Figure 4A). In some cases, the patient’s epiglottis is in omega shape, folded, and formed an arch gateway appearance. In contrast to the expected difficulty or challenges for the DL/VL technique in such a scenario of an omega-shaped epiglottis, 9-11 it is extraordinarily easy to apply styletubation. One can easily pass the stylet-ETT assembly unit through the arch gateway and then acquire the clear glottis visualization (Figure 4B). When the tip of the stylet-ETT unit is in a satisfactory position, the ETT may then be railroaded (advanced) into the trachea using the gentle release of the ETT away from the stopper mounted onto the proximal end of the stylet.

Download full-size image

(A) A 70-year-old woman (164 cm, 82 kg) underwent fasciotomy and debridement. Jaw-thrust maneuver created an LQS Grade 1. The stylet-ETT unit was directly advanced along the midline of the base of the pharynx (denoted by the white arrow). When the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles came to sight, the stylet was tipped up and the glottis view was acquired. (B) A 56-year-old man (167 cm, 69 kg) underwent Da Vinci robotic surgery. The epiglottis was flat and the LQS Grade was 1. The stylet-ETT unit was advanced directly through the space between the epiglottis and posterior pharyngeal wall (denoted by the white arrow).

Download full-size image

(A) A 38-year-old man (178 cm, 120 kg) underwent bariatric surgery. Jaw-thrust maneuver was limited by the obesity status, and the LQS Grade 2 scenario was observed. The stylet-endotracheal tube (stylet-ETT) unit was first turned to the left lateral side of the epiglottis (denoted as the white curved arrow) and swept under the left lateral edge of the epiglottis. Then, the visualization of the glottis opening was acquired. (B) A 68-year-old man (163 cm and 57 kg) underwent urological surgery. An omega-shaped epiglottis was shown, and the LQS Grade 2 was observed. The stylet-ETT unit was then advanced directly underneath and through the arch of the epiglottis (denoted as the white arrow).

It should be emphasized that the abovementioned scenarios are dealt with the patient’s airway secured by a jaw-thrust (or chin-lift) maneuver. When the patient’s epiglottis could not be displaced by any airway maneuver (e.g., Figure 2, LQS Grade 3), another airway manipulation (e.g., assisted by laryngoscopy 12 ) was required to increase the patient’s retropharyngeal space to enhance the success of the styletubation.

References

| 1 |

Luk HN, Luk HN, Qu JZ, Shikani A.

A paradigm shift of airway management: the role of video-assisted intubating stylet technique.

|

| 2 |

Luk HN, Qu JZ, Shikani A.

Styletubation: the paradigmatic role of video-assisted intubating stylet technique for routine tracheal intubation.

Asian J Anesthesiol. 2023;61(2):102-106.

|

| 3 |

Luk HN, Qu JZ, Shikani A.

Styletubation for routine tracheal intubation for ear-nose-throat surgical procedures.

Annal of Otol Head and Neck Surg. 2023;2(3):1-13.

|

| 4 |

Luk, HN, Qu, JZ.

Styletubation versus laryngoscopy: a new paradigm for routine tracheal intubation.

Surgeries. 2024;5(2):135-161.

|

| 5 |

Lee HC, Wu BG, Chen BC, Luk HN, Qu JZ.

Structured routine use of styletubation for oro-tracheal intubation in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgeries—a case series report.

Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(14):1404.

|

| 6 |

Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, et al.

2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway.

Anesthesiology. 2022;136(1):31-81.

|

| 7 |

Shih TL, Koay KP, Hu CY, Luk HN, Qu JZ, Shikani, A.

The use of the Shikani video-assisted intubating stylet technique in patients with restricted neck mobility.

Healthcare. 2022;10(9):1688.

|

| 8 |

Tsay PJ, Yang CP, Luk HN, Qu JZ, Shikani A.

Video-assisted intubating stylet technique for difficult intubation: a case series report.

Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(4):741.

|

| 9 |

Veiga J, Gomes C.

Omega-shaped epiglottis: a challenge.

Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021;71(4):464-465.

|

| 10 |

Barnicle RN, Bracey A.

Uncommon anatomical variation of an epiglottis encountered during emergent endotracheal intubation.

J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2022;3(6):e12861.

|

| 11 |

Görgülü Ö, Koşar MN.

Airway management in a geriatric patient with an omega-shaped epiglottis.

SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2:1223-1225.

|

| 12 |

Jhuang BJ, Luk HN, Qu JZ, Shikani A.

Video-twin technique for airway management, combining video-intubating stylet with videolaryngoscope: a case series report and review of the literature.

Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(11):2175.

|