Abstract

Background

Fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) is one of the regional blocks used to reduce postoperative pain after total hip arthroplasty (THA). Administration of dexamethasone in the loading dose might lengthen pain-free duration and reduce anesthetic consumption.

Methods

Sixty patients undergoing THA with spinal anesthesia and patient-controlled FICB were randomly assigned to receive either 20 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine with 8 mg dexamethasone (Group D, n = 30) or 20 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine alone (Group C, n = 30). Postoperative pain scores, analgesic use, and side effects were assessed over 72 hours.

Results

Postoperative visual analogue scale scores did not differ significantly between groups. The time to first bolus was longer in Group D than in Group C (407.10 ± 305.68 vs. 308.63 ± 212.99 minutes;

Conclusion

The addition of dexamethasone to ropivacaine for FICB after THA can significantly provide a longer duration of analgesia with a lower amount of anesthetic.

Keywords

fascia iliaca block, hip arthroplasty, postoperative pain

Introduction

As the population ages, the prevalence of total hip arthroplasty (THA) is expected to increase. THA is a major surgical procedure associated with significant postoperative pain, leading to dysfunction in multiple organ systems, especially respiratory compromise, hemodynamic instability, and motor function impairment. 1 Optimal pain control facilitates either physical or mental recovery, accelerates early rehabilitation, and therefore reduces several complications such as pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pulmonary infarction.

Pain management after THA remains a topic of debate, with no universally accepted guidelines. Among emerging techniques, the fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) has gained popularity as a regional anesthesia option. By delivering local anesthetic beneath the fascia iliaca, FICB effectively targets the femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, and occasionally the obturator nerves. When performed under ultrasound guidance, this posterior approach to the lumbar plexus offers reliable analgesia while minimizing the adverse effects commonly associated with epidural techniques. 2,3

Ropivacaine has been used worldwide since 1996, as it is proven to have more advantages than bupivacaine due to the lower toxicity on the neural and cardiac systems. 4 To enhance the efficacy of regional blocks, adjuvants such as dexamethasone are often added, given their perioperative benefits in reducing postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting. 5 However, the role of perineural dexamethasone as an adjunct to peripheral nerve blocks remains a subject of ongoing discussion.

To address this question, we conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of FICB using ropivacaine with dexamethasone versus ropivacaine alone for postoperative pain relief following THA.

Methods

Subjects

This prospective randomized study was conducted in the Center of Anesthesiology, Critical Care, and Pain Management in Hanoi Medical University Hospital from April 2024 to September 2024. Sixty patients aged 18 years or older, classified as ASA physical status I-III, and scheduled for THA were enrolled after providing informed consent to receive an FICB. Exclusion criteria included a history of neurological disorders (such as psychological conditions, dementia, or chronic pain) and any contraindication to spinal anesthesia or regional block, including patient refusal or allergy to study medications.

Intervention

After providing informed consent, patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: Group D (n = 30), receiving patient-controlled FICB with ropivacaine combined with dexamethasone, and Group C (n = 30), receiving patient-controlled FICB with ropivacaine alone.

Preoperatively, all patients were instructed on patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) use, visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scoring, and criteria for additional analgesia requests. On the day of surgery, ultrasound-guided FICBs were performed by an attending anesthesiologist using a standardized technique, with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine injected beneath the fascia iliaca to confirm block success. Spinal anesthesia was administered using 5-9 mg of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine and 30 μg fentanyl, adjusted according to patient characteristics.

Postoperatively, when VAS scores exceeded 4, patients received a loading dose: 20 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine combined with 8 mg dexamethasone for Group D, and 20 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine for Group C. The PCA device was programmed to deliver 10 mL boluses of 0.1% ropivacaine with a 15-minute lockout and a maximum of 20 mL per hour. Additionally, all patients received intravenous paracetamol 1 g every 8 hours. If VAS remained ≥ 4 at rest despite two consecutive PCA boluses, rescue analgesia of 30 mg intravenous ketorolac was administered.

Main Outcomes

The primary outcome was duration of painfree after the loading dose, cumulative ropivacaine consumption in 72 hours after THA, and pain scores (VAS scores) at rest and during mobilization. Secondary outcomes included: quadriceps muscle weakness (Bromage score) and adverse effects related to the blocks and local anesthetics.

Ethical Approval

This study is nonexempt human research and was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Hanoi Medical University (IRB number: CKII36/GCN-HMUIRB) on 01-04-2024. The IRB is a registered and accredited ethics committee. All study participants provided effective informed consent prior to enrollment. The Journal has identified that this study involved invasive procedures (regional anesthesia with ropivacaine and dexamethasone), which may carry certain risks to participants.

Results

Sixty patients were enrolled and completed the study. Demographic characteristics were comparable between groups (Table 1).

|

Characteristic |

Group D (n = 30) |

Group C (n = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (year), mean ± SD |

57.37 ± 15.23 |

51.87 ± 13.95 |

0.150 |

|

BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD |

21.75 ± 2.42 |

22.55 ± 2.27 |

0.190 |

|

Gender, n (%) |

|||

|

Male |

25 (83.3) |

25 (83.3) |

1.000 |

|

Female |

5 (26.7) |

5 (26.7) |

|

|

ASA, n (%) |

|||

|

I |

7 (23.3) |

10 (33.3) |

0.668 |

|

II |

21 (70.0) |

19 (63.4) |

|

|

III |

3 (6.7) |

1 (3.3) |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

The time to first bolus was significantly longer in Group D (407.10 ± 305.68 minutes) compared to Group C (308.63 ± 212.99 minutes;

|

Characteristic |

Group D (n = 30) |

Group C (n = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Time to the first bolus (minutes) |

407.10 ± 305.68 |

308.63 ± 212.99 |

0.026 |

|

Bolus counts |

14.53 ± 7.96 |

22.30 ± 9.13 |

0.001 |

|

Ropivacaine consumption (mg) |

210.33 ± 79.64 |

288.00 ± 91.32 |

0.001 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

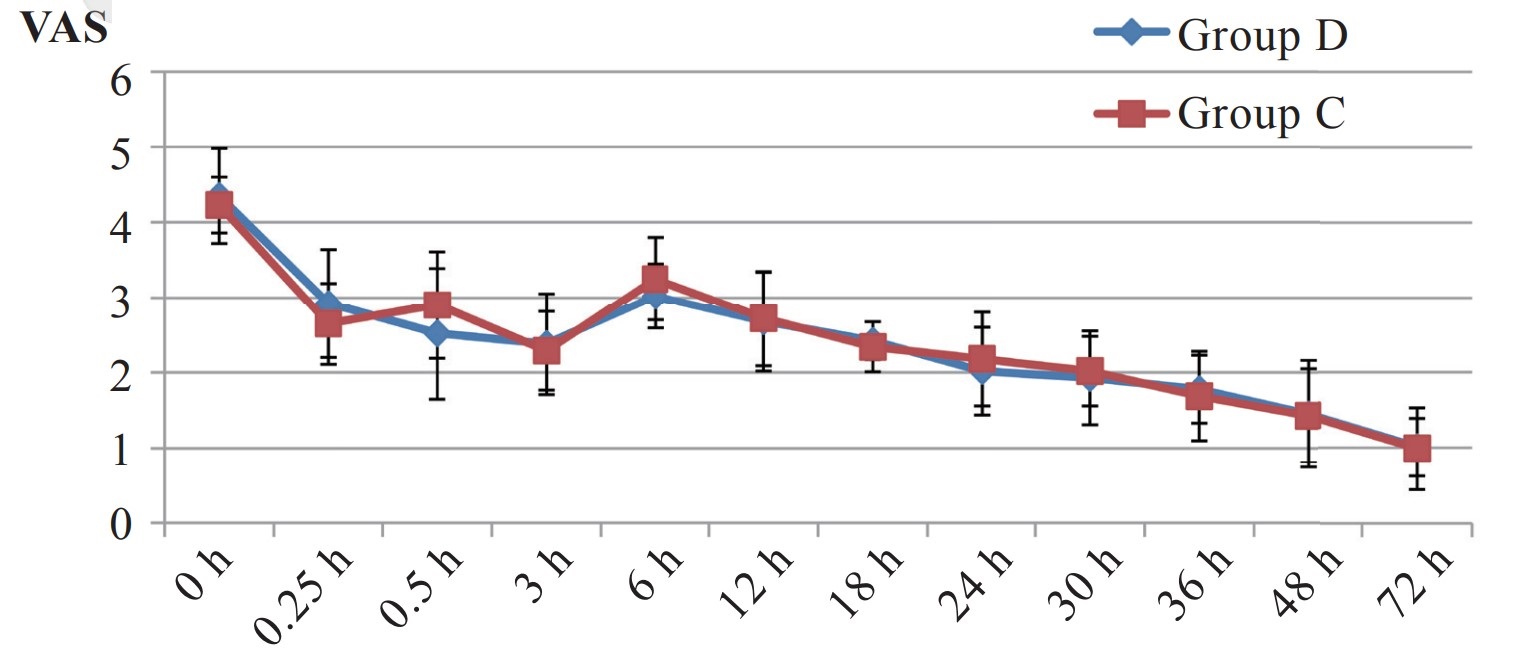

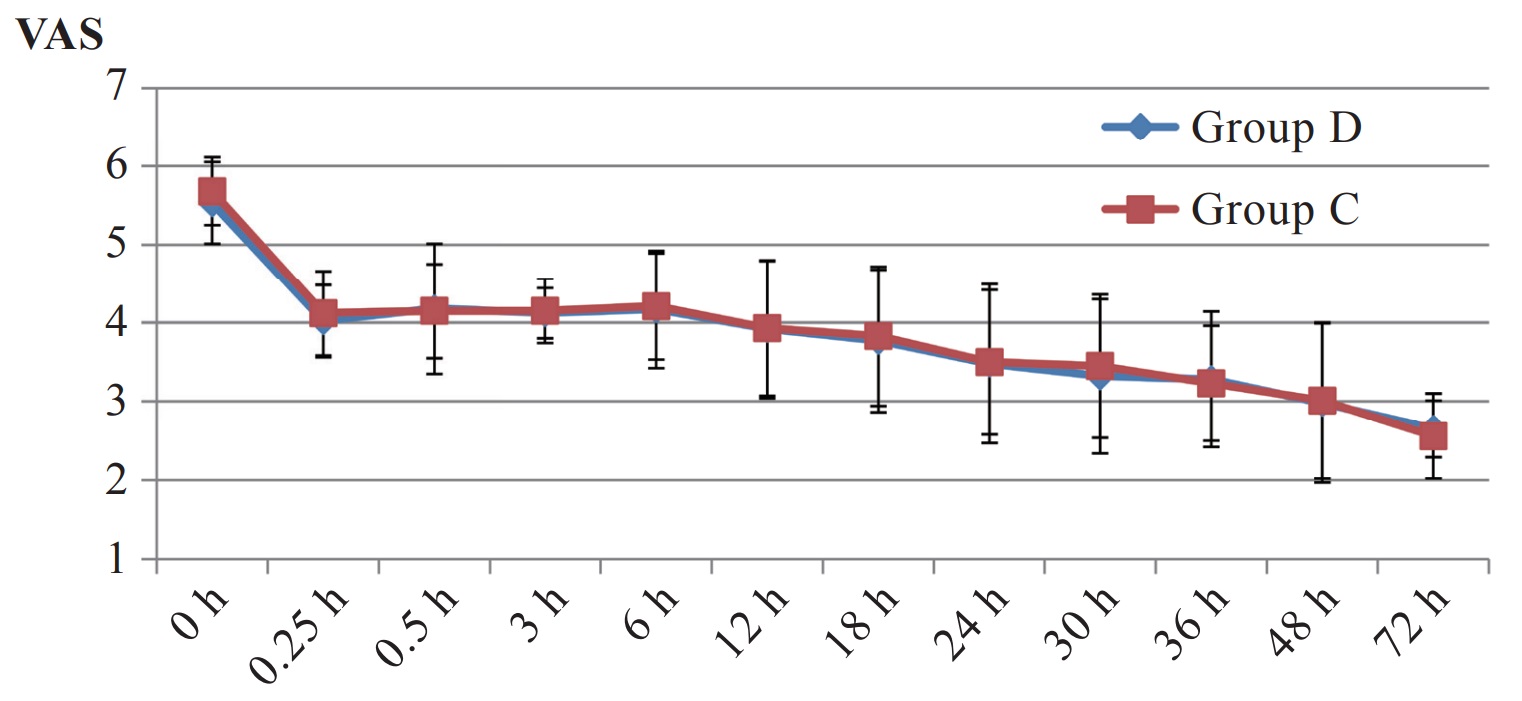

VAS score was comparable in both groups at rest and during mobilization. There was no statistically significant difference in VAS score before the loading dose. Similar results were shown in the VAS score in the next post-operative hours, all of which were lower than or equal to 4 points (Figures 1 and 2).

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Patients in both groups were associated with equivalent rates of quadriceps muscle weakness. Most of the participants did not experience muscle weakness (Bromage 0), and no patients were evaluated with Bromage 2 or Bromage 3 (Table 3).

|

Bromage |

Group D (n = 30) |

Group C (n = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

M0 |

26 (86.67) |

25 (83.33) |

1.000 |

|

M1 |

4 (13.33) |

5 (16.67) |

Side effects related to the blocks comprise pain at the catheter insertion site, insertion in vessels, hematoma or infection at the catheter site, and anesthetic toxicity. We observed pain at the catheter site in only 1 patient from Group D and 2 patients from Group C (no statistically significant difference). None of the other side effects were recorded in our study.

Discussion

Previous publications worldwide have demonstrated that dexamethasone prolongs the duration of local anesthetics when combined. The mechanism of this effect is not fully understood. Some authors have hypothesized that dexamethasone inhibits prostaglandin synthesis and reduces the capillary permeability of fiber nerves to local anesthetics. In vitro studies on mice have shown that corticosteroids inhibit the conduction of pain-transmitting fibers (C fibers and A-delta fibers). Our study supported this hypothesis regarding duration of pain-free time until the first bolus in Group D is significantly longer than in Group C (407.10 ± 305.68 minutes vs. 308.63 ± 212.99 minutes). In a randomized, double-blinded study conducted in 2022, Nainegali et al. 6 evaluated the use of dexamethasone as an adjuvant to ropivacaine for FICB in patients with femur fractures. They found that the mean time to demand rescue analgesia after the block was 616.15 ± 71.45 minutes in the dexamethasone group, compared to 556.40 ± 68.18 minutes in the control group. This duration was longer than our results due to a higher volume of ropivacaine (40 mL and 20 mL).

VAS scores at rest and during mobilization before the loading dose were higher than 4 points and comparable between groups. Following the loading dose, the VAS score decreased, demonstrating a downward trend on postoperative days 2 and 3 compared to the first day. These results indicated that both groups received effective pain relief.

Quadriceps muscle weakness was graded at the maximum of Bromage 1 in both groups, with no statistically significant difference in the proportions. This effect resulted from the femoral nerve motor block. Additionally, no participants were assessed as Bromage 2 or Bromage 3, as we administered bolus doses with the lowest volume and concentration necessary to achieve effective analgesia. Minimal side effects of FICB were observed, but mostly mild, suggesting that this block is safe for patients after THA.

Our study has some major strengths. Firstly, there are very few studies using patient-controlled FICB, and this may pave the way for further research on the efficacy of FICB in pain management after THA. Secondly, we excluded patients with failed blocks so that the comparison between groups would be more accurate. However, our study was limited by several limitations. Firstly, this study comprised a small sample size of 30 patients in each group. Thus, the outcomes and conclusions should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, in-depth analyses should be performed to optimize the application of PC-FICB in pain management after THA.

Conclusion

Growing evidence suggests that FICB using ropivacaine combined with dexamethasone is an effective and reliable strategy for postoperative pain relief after THA. This combination prolongs the duration from the loading dose to the first bolus, reduces anesthetics consumption and times of bolus compared to ropivacaine only.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the board of Hanoi Medical University Hospital for supporting our research.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

| 1 |

Ferrata P, Carta S, Fortina M, Scipio D, Riva A, Di Giacinto S.

Painful hip arthroplasty: definition.

Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2011;8(2):19-22.

|

| 2 |

Bang S, Chung J, Jeong J, Bak H, Kim D.

Efficacy of ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca compartment block after hip hemiarthroplasty.

Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(39):e5018.

|

| 3 |

LaJeunesse M, Cronin A, Takahashi M, Knudsen J, Nagdev A.

Control hip fracture pain without opioids using ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca compartment block.

ACEP Now. Published January 25, 2018. Accessed June 20, 2023.

|

| 4 |

Atabekoğlu S, Bozkirli F.

Comparison of the clinical effects of intrathecal ropivacaine and bupivacaine in geriatric patients undergoing transurethral resection.

Gazi Med J. 2007;18(4):182-185.

|

| 5 |

Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, et al.

Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Anesth Analg. 2003;97(1):62-71, table of contents.

|

| 6 |

Nainegali DS, Naik DD, Dubey DS, Ranganath D, Bc DV.

Dexamethasone as adjuvant to ropivacaine in pre-operative ultrasound guided fascia iliaca compartment block for positioning patients with femoral fracture for central nervous blockade: A double blinded randomized comparative clinical study.

Clinical Medicine. 2022;9(6).

|