Abstract

Objective

The incidence of airway obstruction has been reported to be 1.2–6.1% after cervical spine surgery and up to 27% in posterior occipito-cervical spinal fusion. Communication between the anesthesiologist, surgeon, and staff responsible for postoperative care, and the identifi cation of patients at risk of airway complications are important. We aimed to determine the incidences of delayed extubation and reintubation, and the factors related to delayed extubation after cervical spine surgery.

Methods

A review was conducted of the medical records of patients who underwent cervical spine surgery in the orthopedic and neurosurgery units, Siriraj Hospital, between January 2012 and May 2017. The data included demographics, perioperative airway management, postoperative airway complications (delayed extubation and reintubation), and outcomes.

Result

Of the 506 patients analyzed, delayed extubation occurred in 116 (22.9%), and 15 (3.0%) were reintubated. The independent related factors for delayed extubation were blood loss ≥ 300 mL (odds ratio [OR], 2.71; 95% confi dence interval [CI], 1.33–5.49); intraoperative fl uid administration ≥ 2,000 mL (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.08–4.36); anesthetic time ≥ 300 min (OR, 3.74; 95% CI, 1.83–7.63); and case fi nished after service hours (OR, 3.18; 95% CI, 1.73–5.88).

Conclusion

The incidence of delayed extubation in cervical spine surgery patients was high, and reintubation was common. Anesthesiologists should be cognizant of the related risk factors before deciding between immediate or delayed extubation.

Keywords

delayed extubation, cervical spine surgery, reintubation

Introduction

Cervical spine surgery is a common procedure in orthopedic and neurosurgery units. Postoperative airway obstruction is a rare but potentially fatal complication. The incidence of airway obstruction has been reported to be 1.2–6.1%1-4 in cervical spine surgery and up to 27% in posterior occipito-cervical spinal fusion.5 The etiologies are laryngopharyngeal edema resulting from retraction during anterior cervical surgery, or mucosal edema arising from venous pooling caused by prone positioning and intravenous fl uid administration during posterior surgical surgery.6 The tracheal mucosa has been reported to demonstrate marked edema at the C2–4 levels and for a maximal period of 12–72 h postoperatively.7 Emergency airway management by reintubation or tracheostomy may be needed, but it could cause hypoxia, displacement of instruments, respiratory tract infections, or death.

Although delaying extubation until resolution of a mucosal edema prevents postoperative airway obstruction, prolonged intubation has some adverse impacts as well. Good communication between the anesthesiologist, surgeon, and staff responsible for postoperative care, and the identification of patients at risk of airway complications, are important. Factors contributing to delayed extubation were reported by Palumbo et al. as primary risk factors related to the surgical procedure, and secondary risk factors such as patient’s condition, anesthetic concerns, and institution resources.6

Pangthipampai et al. reported the contributing factors of incidences of delayed extubation occurring at our institute between 2002 and 2007.8 The significant factors were age > 60 years, a neurological deficit, surgery > 2 levels, duration > 180 min, and fiberoptic intubation. Nowadays, surgical and anesthetic techniques are more advanced, and although surgical time has increased, there is less tissue trauma. As the number of beds available in intensive care units (ICUs) is limited, a decision to delay extubation should be based on current evidence, and an institute should develop extubation protocols for patient safety.9

The aims of this study were to determine the incidences of delayed extubation and reintubation, and to identify the factors related to delayed extubation after cervical spine surgery.

Methods

Study Design

After research ethics board approval (SI 367/2016), a retrospective study was carried out by examining the medical records of all patients who underwent cervical spine surgery at Siriraj Hospital between 2012 and 2017. All cervical spine operations were performed in two surgical units: orthopedic and neurosurgery. A total of 506 patients (253 in the orthopedic unit, and 253 in the neurosurgery unit) were reviewed by two investigators to minimize data error. The collected data were patient characteristics, perioperative data, airway management (the type of equipment used, and the ease of intubation, as recorded by operators in anesthetic records), airway complications (failed intubation, delayed extubation, and reintubation), intraoperative data, and outcomes.

Delayed extubation was defined as a patient who had not been extubated at the end of the surgery or before leaving the operating room. The data for the delayed extubation patients were reviewed in detail to identify related factors.

The other outcomes of interest included ventilator days, lengths of ICU and hospital stays, and patient discharge statuses.

Statistical Analysis

The estimated delayed intubation rate was 20% (from pilot observational study), with a 5% type I error rate and an 80% power; the sample size was calculated to be 246 patients. We estimated the reintubation rate was 5% with a 2% error rate,1-4 a 2-sided type I error = 0.05, and an 80% power; using the nQuery Advisor 6.0 program (Statsols, Cork, Ireland), the sample size was determined to be 457 patients. We collected 506 patients to accommodate both airway-related complications (reintubation and delayed extubation) and the possibility of dropouts due to incomplete data.

All values were reported as a mean ± standard deviation, median (ranges), or number (%), as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions using the stepwise-selection method (95% confidence interval [CI]) were performed to assess the possible risk factors related to delayed extubation. A p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Data were analyzed using PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

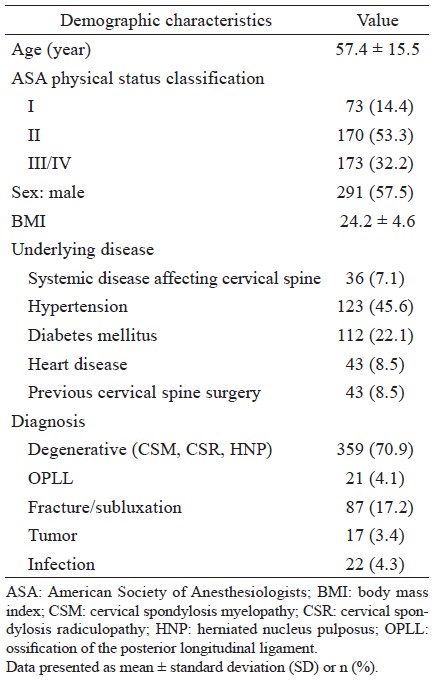

A total of 506 patients were included in the analysis. The patients’ demographic data were shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 57.4 ± 15.5 years. Mainly (67.7%) of the patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification I–II. Mean body mass index was 24.2 ± 4.6 which was not obese. Only 7% of the cases had systemic diseases affecting cervical spines such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and only 8.5% had histories of cervical spine surgery in the past. The main diagnosis was degenerative disease (70.9%) such as cervical spondylosis myelopathy, cervical spondylosis radiculopathy, and herniated nucleus pulposus. Fracture or subluxation was 17.2%, and 7.7% of the cases were diagnosed with tumor or infection.

Download full-size image

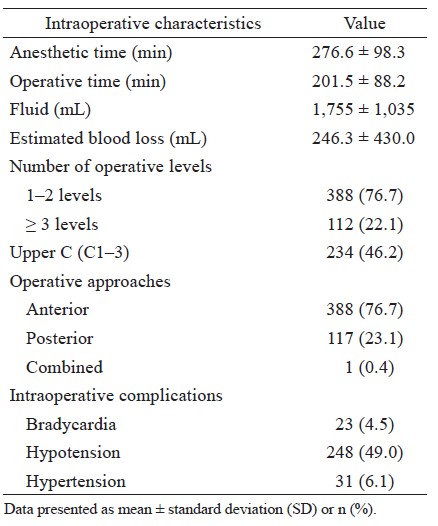

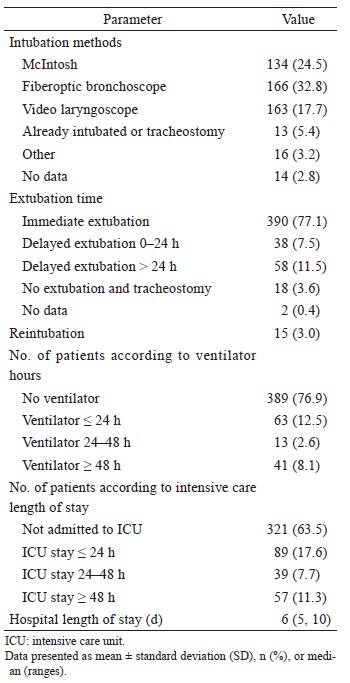

From the intraoperative data (Table 2), the anesthetic time and the operating time was 276.6 ± 98.3 min and 201.5 ± 88.2 min, respectively. Mean intravenous fluid and blood loss were 1,755 ± 1,035 mL and 246.3 ± 430.0 mL. Most of the cases (76.7%) were operated in 1–2 levels of the cervical spine and 46.2% involved C1–3 levels. About 76.7% of operations were done in the anterior approach. The common intraoperative complication was hypotension which was not severe and can corrected by minimal doses of vasopressor. The inhalation agent was used for the maintenance period except for one case in our study that used intraoperative neuromonitoring. About neuromuscular blocking agents, most of the cases (73.1%) were received atracurium, cisatracurium 21.5% and rocuronium 2.2%. The last dose of muscle relaxant usually was at least 30 min before finishing the operation and the recovery from the effect of muscle relaxants was assessed using subjective methods such as eye-opening and sustained handgrip after giving anticholinesterases (neostigmine) at the end of surgery. The airway management was shown in Table 3 which 42.2% of the cases were intubated by regular or video laryngoscope and 32.8% by fiberoptic bronchoscope. Three hundred and ninety cases (77.1%) were immediately extubated in the operating theater by the anesthesiologists’ decision. About 11.5% were remained intubation more than 24 h and 3.6% were decided not to extubate and end up with tracheostomy. The incidence of delayed extubation and reintubation were 22.9 and 3.0%, respectively. About 36.6% of the cases were admitted in the ICU and 23.1% were needed ventilator support. The median of hospital length of stay was 6 (5, 10) days.

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

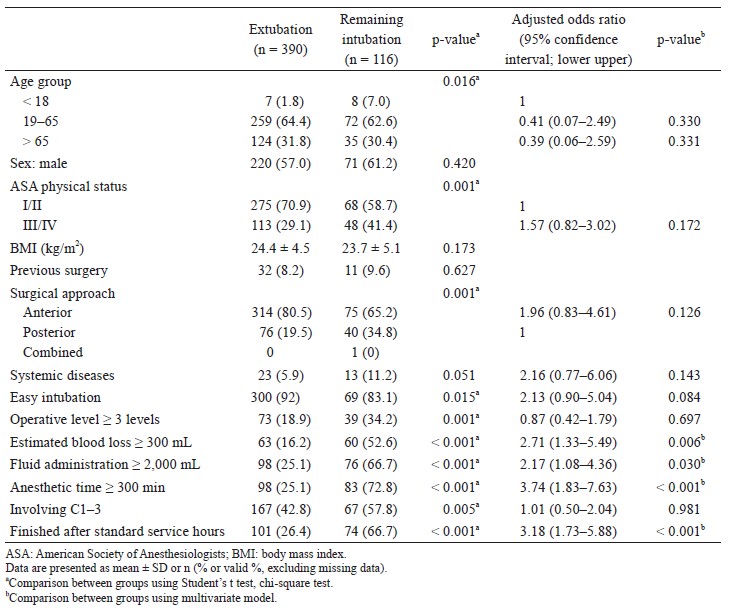

As shown in Table 4, from the univariable analysis found the factor that may be related to delayed extubation in our academic hospital were age > 65 years, ASA III–IV, history of difficult intubation, operative level > 3 levels, posterior surgical approach, involving C1–3, blood loss > 300 mL, intravenous fluid > 2,000 mL, anesthetic time > 300 min and finished after standard service hours. The multivariable analysis was done in all related factors with a p-value < 0.1. The result revealed the independent factor such as an estimated blood loss ≥ 300 mL, an intraoperative fluid administration ≥ 2,000 mL, an anesthetic time ≥ 300 min, and finishing after standard service hours were related to delayed extubation.

Download full-size image

Discussion

The incidences of delayed intubation and reintubation were 22.9 and 3.0%, respectively. The related factors for delayed extubation were blood loss ≥ 300 mL, fluid administration ≥ 2,000 mL, anesthetic time ≥ 300 min, and cases finishing after standard service hours.

To avoid serious postoperative airway complications such as airway edema, airway obstruction, and emergency airway management in suspected difficult airway patients, many anesthesiologists choose to delay extubation in patients at risks. Delayed extubation has a significant impact on ventilator use and ICU or intermediate-care stay, and it should not be routinely used for every case. The incidence of delayed extubation varies with different definitions. Some authors have defined delayed extubation as an extubation occurring after 24 h of intubation,1 or after 48 h of intubation.10 However, delayed extubation is mostly defined as no extubation at the end of surgery. In the present study, only 84.6% were extubated within 24 h, which is lower than the proportions reported by other studies.1,11 Longer intubation periods are associated with longer ICU stays and higher incidences of ventilator associated pneumonia.

The need for reintubation could be caused by an airway obstruction or respiratory complications (pneumonia or aspiration). Reintubation increases ventilator use, and it prolongs ICU and hospital stays. The 3% incidence of reintubation found in the present study is comparable with the rates reported by other studies.1,2,12 It is therefore necessary to have both a backup extubation plan as well as airway equipment on hand for reintubation in the event that an airway obstruction occurs.

Although an ASA physical status of III/IV or a comorbidity (such as obesity or asthma) has been shown to be related to delayed extubation by some studies,1,4,9,13 these factors were not found to be related by other studies.13,14 In elective spine surgery, stable comorbidities may not affect a decision to delay extubation. High levels of blood loss or blood transfusion,1,13,15,16 excessive fluid administration,4,14,15 and prolonged anesthetic or operative times1,14-16 have been shown to be factors that are significantly related to delayed extubation. In this study, the average blood loss was only 200–300 mL, so there was no need for a large volume of crystalloid administration; too much crystalloid administration could increase the degree of cervical tissue edema. In the present study, a case end-time after standard service hours was found to be a highly significant factor for patients remaining intubated given that less experienced staff (i.e., junior staff or anesthetic trainees) usually cover cases occurring after standard service hours; this finding is in concord with the results of Anastasian et al.4 Based on the present study’s data, an airway management protocol after cervical spine surgery (covering the intubation method, factors to be considered when deciding to delay extubation, and extubation guidelines) should be developed and used to ensure patient safety and appropriate resource utilization. With this protocol the related factor due to finishing after standard service hours must be reduced.

This study has the inherent limitations of a retrospective review. There were some missing details, such as whether a reintubation was performed due to an obstruction, a respiratory failure, or both. In the case of a small number of reintubations, it was not possible to identify any related risks. A multicenter or national study may be needed to find the true incidence of, the causes of, and the factors related to, reintubation.

Conclusion

The incidence of delayed extubation in cervical spine surgery patients remains high, and reintubation is common. Anesthesiologists should recognize the related risk factors when deciding whether to immediately perform or delay extubation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Miss Julaporn Pooliam for her statistical assistance and Miss Chusana Rungjindamai for her substantial administrative support.

Funding

This research was supported by the Siriraj Research Development Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University (grant number: [IO] R016031004).

References

| 1 |

Kim M, Rhim SC, Roh SW, Jeon SR.

Analysis of the risk factors associated with prolonged intubation or reintubation after anterior cervical spine surgery.

J Korean Med Sci 2018;33:e77.

|

| 2 |

Sagi HC, Beutler W, Carroll E, Connolly PJ.

Airway complications associated with surgery on the anterior cervical spine.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:949–953.

|

| 3 |

Manninen PH, Jose GB, Lukitto K, Venkatraghavan L, El Beheiry H.

Management of the airway in patients undergoing cervical spine surgery.

J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2007;19:190–194.

|

| 4 |

Anastasian ZH, Gaudet JG, Levitt LC, Mergeche JL, Heyer EJ, Berman MF.

Factors that correlate with the decision to delay extubation after multilevel prone spine surgery.

J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2014;26:167–171.

|

| 5 |

Sheshadri V, Moga R, Manninen P, et al.

Airway adverse events following posterior occipito-cervical spinal fusion.

J Clin Neurosci 2017;39:124–129.

|

| 6 |

Palumbo MA, Aidlen JP, Daniels AH, Bianco A, Caiati JM.

Airway compromise due to laryngopharyngeal edema after anterior cervical spine surgery.

J Clin Anesth 2013;25:66–72.

|

| 7 |

Suk KS, Kim KT, Lee SH, Park SW.

Prevertebral soft tissue swelling after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate fixation.

Int Orthop 2006;30:290–294.

|

| 8 |

Pangthipampai P, Chinachoti T, Halilamien P, et al.

Factors contributing to delayed extubation after cervical spine surgery in Siriraj Hospital.

Siriraj Med J 2011;63:123–127.

|

| 9 |

Kim M, Choi I, Park JH, Jeon SR, Rhim SC, Roh SW.

Airway management protocol after anterior cervical spine surgery: analysis of the results of risk factors associated with airway complication.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:E1058– E1066.

|

| 10 |

Nandyala SV, Marquez-Lara A, Park DK, et al.

Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of postoperative airway management after cervical spine surgery.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E557–E563.

|

| 11 |

Schroeder J, Salzmann SN, Hughes AP, Beckman JD, Shue J, Girardi FP.

Emergent reintubation following elective cervical surgery: a case series.

World J Orthop 2017;8:465–470.

|

| 12 |

Cavallone LF, Vannucci A.

Extubation of the difficult airway and extubation failure.

Anesth Analg 2013;116:368–383.

|

| 13 |

Epstein N.

Ossification of the cervical posterior longitudinal ligament: a review.

Neurosurg Focus 2002;13.

|

| 14 |

Kwon B, Yoo JU, Furey CG, Rowbottom J, Emery SE.

Risk factors for delayed extubation after singlestage, multi-level anterior cervical decompression and posterior fusion.

J Spinal Disord Tech 2006;19:389–393.

|

| 15 |

Li F, Gorji R, Tallarico R, et al.

Risk factors for delyed extubation in thoracic and lumbar spine surgery: a retrospective analysis of 135 patients.

J Anesth 2014; 28:161–166.

|

| 16 |

Epstein NE, Hollingsworth R, Nardi D, Singer J.

Can airway complications following multilevel anterior cervical surgery be avoided?

J Neurosurg 2001;94(2 Suppl):185–188.

|