Outline

Abstract

Background: The modified Mallampati classification (MMC) provides an estimate of the tongue size relative to the oral cavity size, and is a usual screening tool fo predicting diffi cult laryngoscopy. Previous studies have indicated an increase of MMC during the progression o pregnancy, but there is no comprehensive study in pregnant women undergoing cesarean delivery. The primar aim of this study was to evaluate the MMC before and after cesarean delivery.

Methods: This is a prospective observational study of 104 women who underwent cesarean section. MMC, thyromental distance, neck circumference, and upper lip bite test wer evaluated at 4 different time points: during the pre-anesthetic visit (T0) and at 1 (T1), 6 (T2), and 2 (T3) hours after delivery. Factors evaluated for their predictive validity included gestational weight gain operation time, amount of intravascular fluids, oxytocin dosage, and blood loss. The correlation between each factor and the MMC classification was tested by logistic regression.

Results: From 104 participants, 59.6% experienced Mallampati class changes. The proportions of patients classified as Mallampati III and IV at different time points were: T0 = 48.1% (MM III only), T1 = 75.0%, T2 = 80.8%, and T3 = 84.6%, respectively. Gestational weight gain, duratio of surgery, anesthetic method, blood loss, oxytocin dosage, or amount of intravenous fl uid were no correlated with the MMC change.

Conclusion: The number of patients with initial Mallampati III was high. In addition, a significant increase in MMC occurred after cesarean delivery. The data confi rm the particula risk status of women undergoing cesarean delivery particularly regarding airway anatomy.

Keywords

bronchial blocker, double-lumen tube, lung separation, postoperative outcomes

Introduction

Airway management in obstetric anesthesia can be challenging due to pregnancy related physiological changes, namely airway edema, breast engorgement, or restricted neck mobility.1 Various factors, such as fluid overload or the anti-diuretic effect of oxytocin, may contribute to these changes.2,3 Therefore, a higher incidence of failed intubation has been found among obstetric than among non-obstetric patients.4,5 In addition, women in labor have a reduced functional residual capacity, leading to an increased risk of pulmonary dysfunction as shown among others by Mushambi and Kinsella.6

To reduce the risk of airway complications, neuraxial anesthesia is the most common method used for cesarean section (CS).7 However, general anesthesia (GA) is still indicated in cases of urgency, inadequate neuraxial anesthesia or in patients with contraindications for neuraxial anesthesia. Therefore, particularly in thes patients’ meticulous airway evaluation and cautious airway management are required.

Though it is not proven to be 100% reliable for predicting airway problems, the modified Mallampati classification (MMC) provides a rough estimate of tongue size relative to the size of the oral cavity.8 Rocke and colleagues9 showed that the likelihood of having a difficult laryngoscopy increased 7.6 and 11.3-fold among obstetric patients with MMC III and IV, respectively. Therefore, MMC remains a useful airway assessment in the obstetric population.

Previous studies have indicated that the MMC increases in the course of pregnancy as well as after vaginal delivery.10,11 However, there is no comprehensive prospective study evaluating the airway changes during CS. Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was to evaluate MMC before and after cesarean delivery. As a secondary outcome, we analyzed additional potential risk factors for MMC changes.

Methods

Patient Population

This prospective observational study was conducted between February 2016 and August 2016 in a tertiary hospital, after approval by the ethics committee of Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand (ID11-58-18). The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02687282). Written informed consent was provided by all patients.

Inclusion criteria were pregnant women aged ≥ 18 years, scheduled for cesarean delivery, whereas patients diagnosed with preeclampsia, history of pulmonary edema or congestive heart failure MMC class IV, or refusing to participate in the study had been excluded.

Airway examinations were conducted during the preoperative visits by 2 of the authors (Lisa Sangkum and Atchara Prachayawong). All patients underwent either spinal (1 epidural) or GA for cesarean delivery, depending on patients’ and anesthesiologists’ decision.

Airway Assessment Methods

The following 4 parameters of airway assessment were evaluated by 2 of the authors, who are experienced anesthesiologists (Lisa Sangkum and Atchara Prachayawong) at 4 time points: during the pre-anesthetic visit (T0), 1 hour after the operation (T1), 6 hours after the operation (T2), and 24 hours after the operation (T3).

(1) MMC is graded as follows: class I = soft palate, fauces, uvula, and pillars are visible; class II = soft palate, fauces, and uvula are visible; class III = soft palate and base of uvula are visible; class IV = soft palate is not visible. Any change in the MMC after delivery, compared with the pre-delivery state, was recorded as the primary outcome.

(2) Inter-incisor distance is the distance between the upper and lower incisors.

(3) Thyromental distance (TMD) is defined as the distance from the thyroid cartilage to the mental prominence, with the neck fully extended.

(4) Upper lip bite test (ULBT) is a test to determine the capacity for mandibular movement and the architecture of the teeth. The ULBT is graded as follows: class I = lower incisors biting the upper lip, making the mucosa of the upper lip totally invisible; class II = the same biting maneuver but revealing a partially visible mucosa; class III = the lower incisors fail to bite the upper lip.

(5) Neck circumference (NC) was measured at the most prominent portion of the thyroid cartilage.

Anesthetic Technique

Spinal or epidural anesthesia was applied at L3/4 or L4/5 according to anesthesiologists’ decision. A 27-G Quincke or 18-G Touhy needle respectively was used for neuraxial anesthesia with the patient in lateral position. Bupivacaine 10–15 mg with morphine 0.2 mg and Lidocaine 150–200 mg with fentanyl 25–50 mcg was given for spinal and epidural anesthesia, respectively. Then, patients were placed in 15° left lateral tilt position. Intravenous ephedrine 6–12 mg was given intraoperatively in case of systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg or in case of hypotonia accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or dizziness.

GA was chosen in case of contraindication for neuraxial anesthesia or the need of urgent cesarean delivery, using propofol (1–2 mg/kg), succinylcholine (1.0–1.5 mg/kg) for rapid sequence induction, atracurium (0.2 mg/kg), and morphine (0.1 mg/kg, after delivery).

All patients received standard monitoring including automatic blood pressure control, 3-lead electrocardiogram, pulse oximeter, or in case of GA capnography.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Sample Size Estimation

Sample size calculation was performed based on our pilot study, in which 52% of pregnant women showed a 1 grade increase in MMC 24 hours after delivery. The confi dence level used for statistical judgement was 1 – α (where α is 0.05) and a power of 0.8. The required sample size was 96 participants.

Data Analysis

Patient characteristic data are presented with descriptive statistics, as mean ± standard deviation, median and interquartile range, frequency, or percentage. Friedman analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare pre-labor and post-labor airway classes and ordinal classifi cations taken on the same patient. Oneway ANOVA was used for evaluation of TMD and NC. Spearman correlation was used to analyze the impact of risk factors on pre-, post-change of MMC; in detail weight gain at the time of pregnancy, operation time, blood loss, amount of IV fl uid, and anesthetic procedure. For all analyses, a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically signifi cant.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Demographics

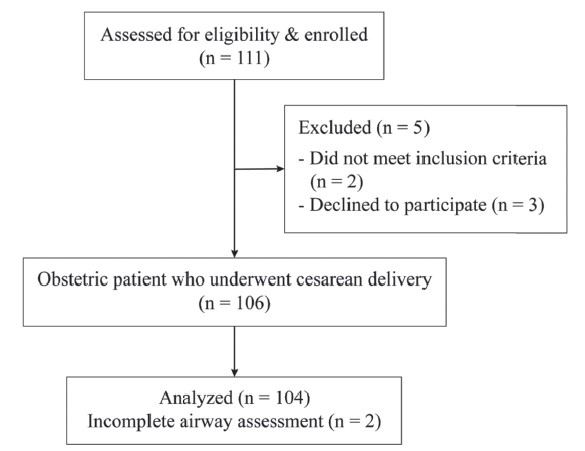

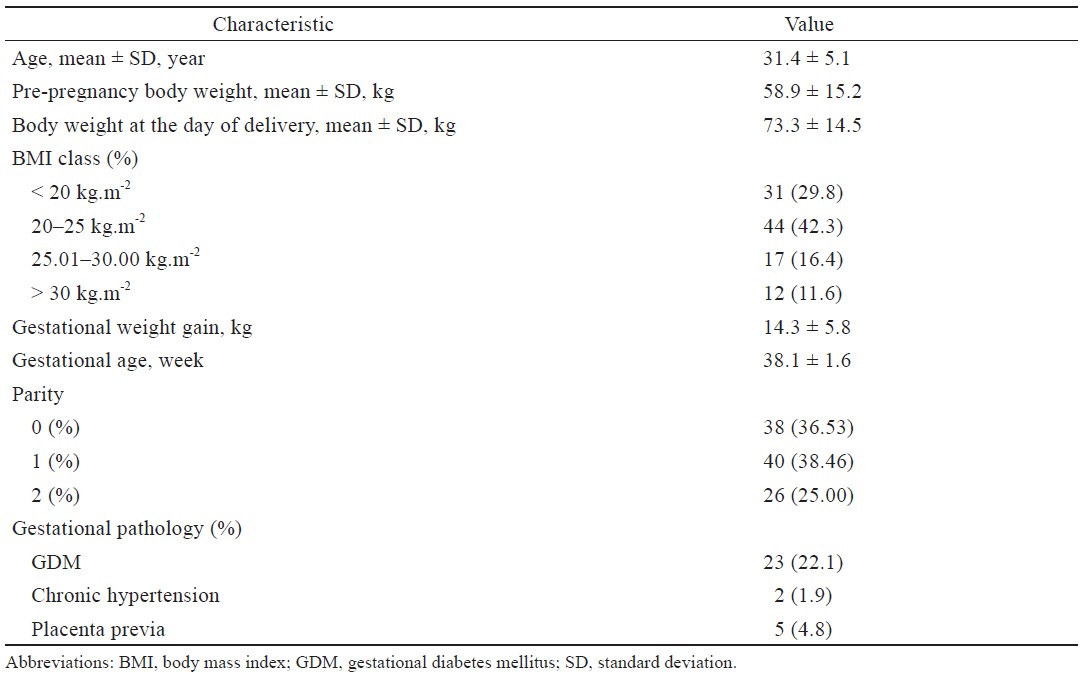

Of 111 patients assessed for eligibility, 5 refused to participate or did not meet the inclusion criteria, whereas 2 patients were lacking the complete data, leaving 104 obstetric patients for analyzing (Figure 1). The average age of the patients was 31.4 (5.1) years, and the weight during pregnancy was 58.9 (15.2) kg. Twelve women were body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 (11.6%) and 17 were BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (16.4%).

Download full-size image

Thirty-eight women (36.53%) were nulliparous. Twenty-three (22.1%), 5 (4.8%), and 2 (1.9%) women were diagnosed gestational diabetes, placenta previa, and gestational hypertension, respectively. Descriptive summary statistics are shown in Table 1.

Download full-size image

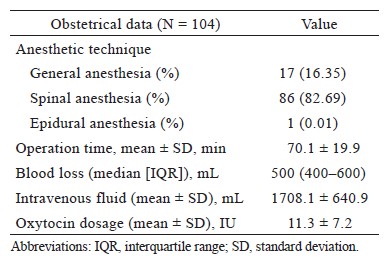

Most patients underwent CS under spinal anesthesia (82.69%). The average blood loss, amount of intraoperative fluid administration, and oxytocin dosage were 500 mL, 1,708 (640.9) mL, and 11.3 (7.2) unit, respectively (Table 2).

Download full-size image

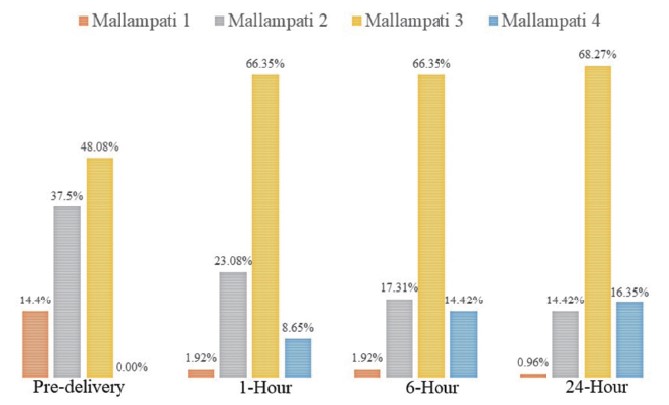

Among 104 included patients, MMC increased 1 grade in 54 (51.9%) and 2 grades in 8 (7.7%); it did not change in 42 (40.4%) at 24 hours after delivery (T3) when compared with the pre-delivery MMC stage (T0). Overall, at pre-delivery stage (T0), 50 patients (48.08%) were MMC class III and after delivery, 88 patients (84.60%) had MMC classes III and IV (Figure 2).

Download full-size image

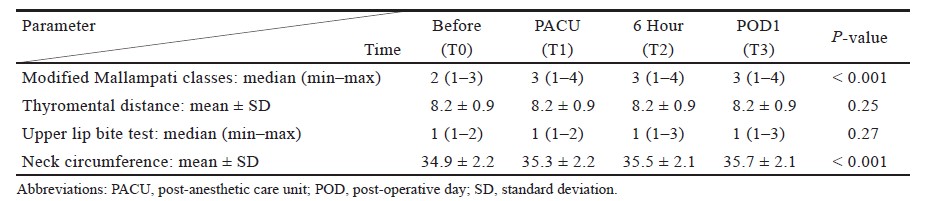

Comparing with the pre-delivery data, MMC score as well as NC showed a statistically significant increase (P < 0.001), whereas TMD and ULBT remained unchanged (Table 3).

Download full-size image

There was no significant correlation between MMC changes and gestational weight gain, duration of surgery, estimated blood loss, anesthetic technique, or volume of intraoperative IV fluids.

No patient experienced any serious complication, such as intubation failure, aspiration, or airway injury.

Discussion

In this study, 59.6% of the obstetric patients who underwent cesarean delivery showed an increase in their MMC at 24 hours after surgery when compared with the preoperative status. These changes were irrespective of any additional risk factors including the anesthetic technique.

Our results concur with the findings of Ahuja et al.,12 who compared normotensive with pre-eclamptic asian parturients, finding significant worsening of Mallampati score from prelabor to 24–48 hours post-delivery in both groups. Including women with vaginal delivery, they also found a strong correlation between total duration of labor and change of Mallampati grade, something we cannot contribute to with our CS-only data. Our data are not in accordance with Hu et al., comparing 86 parturients with vaginal delivery and 90 with CS. They reported only 26.7% MMC increases after CS, but 45.3% increases in the vaginal delivery group within 24 hours.13,14 Thus, MMC increase in our CS parturients was about double compared to them, whereas Hu’s sample was averaged 1.6 years younger, wit a slightly higher BMI, which does not comprehensibly explain the diffences in MMC deviation. Similar to us and Ahuja et al., Guru et al. found no impact of operative time, intraoperative IV fluid administration, and oxytocin dosage on changes of Mallampati score.12,13 However, we observed that the increase in Mallampati class was most pronounced at 24 hours after delivery, whereas Hu et al.14 reported the maximal change after 6 hours. Further studies may address the described discrepancies.

The pathophysiology underlying MMC change after delivery is not completely understood. Decrease of oral pharyngeal space was measured previously using acoustic refl ectometry15 and airway sonography.16 The potential causes of the observed airway changes were hypothesized to be maternal weight gain, fluid administration, or a decrease of oncotic pressure.17,18 The antidiuretic properties of oxytocin were also postulated as an aggravating factor that could lead to increased soft tissue edema and a subsequent increase in the Mallampati class.2,3 None of these suggestions are supported by our findings.

We found out that only MMC and NC significantly changed after cesarean delivery, whereas ULBT and TMD were not affected. During the preoperative period and at 24 hours after surgery, the MMC classes of III or greater accounted for 48.0% and 84.6% of the participants, respectively. Patients with MMC greater III are identifi ed to be associated with difficult intubation;9 therefore, immediate examination of the airway is imperative before induction of GA, rather than relying on information from the pre-delivery period. Examples of clinical scenarios are patients with contraindications for neuraxial anesthesia or in need of urgent cesarean delivery. This applies also to patients experiencing post-delivery complications, requiring reoperation. Anesthesiologists should be aware of difficult airway management in this specific patient population.

This study had some limitations. One limitation was that the time points chosen for airway evaluation were preoperatively and 1, 6, and 24 hours after delivery; therefore, airway changes beyond these time points were not known. An individual error may have occurred on the part of the respective participant when opening her mouth for evaluation. However, we trained each subject beforehand to open her mouth as wide as possible, whereas the airway was evaluated by 2 well trained anesthesiologists applying identical criteria. A third limitation is that we excluded patients with complex co-morbidity, such as preeclampsia, which is not a rare condition in these patients. Further studies are needed address this particular group.

Conclusion

Pregnant women’s MMC score before delivery is often high. When undergoing cesarean delivery, it may increase even further. The findings of this study emphasize that MMC is not static but can change over a short interval after cesarean delivery. Anesthesiologists should generally expect the probability of difficult airway management in this population, preas well as postoperatively.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to declare as it relates to the contents of this manuscript.

Clinical Trial Registration

This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT 02687282.

Disclosures

No financial support or product/research disclosures.

References

| 1 |

Lesage S.

Cesarean delivery under general anesthesia: Continuing Professional Development.

Can J Anaesth.

2014;61(5):489-503.

|

| 2 |

Farcon EL, Kim MH, Marx GF.

Changing Mallampati

score during labour.

Can J Anaesth. 1994;41(1):50.

|

| 3 |

Dobb G.

Laryngeal oedema complicating obstetric anaesthesia.

Anaesthesia. 1978;33(9):839-840.

|

| 4 |

Samsoon GL, Young JR.

Difficult tracheal intubation: a

retrospective study.

Anaesthesia. 1987;42(5):487-490.

|

| 5 |

Lyons G.

Failed intubation. Six years’ experience in a teaching maternity unit.

Anaesthesia. 1985;40(8):759-762.

|

| 6 |

Mushambi MC, Kinsella SM.

Obstetric Anaesthetists’

Association/Difficult Airway Society difficult and failed

tracheal intubation guidelines—the way forward for the

obstetric airway.

Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):815-818.

|

| 7 |

Jenkins JG, Khan MM.

Anaesthesia for Caesarean section:

a survey in a UK region from 1992 to 2002.

Anaesthesia.

2003;58(11):1114-1118.

|

| 8 |

Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al.

A clinical

sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective

study.

Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;32(4):429-434.

|

| 9 |

Rocke DA, Murray WB, Rout CC, Gouws E.

Relative risk

analysis of factors associated with difficult intubation in

obstetric anesthesia.

Anesthesiology. 1992;77(1):67-73.

|

| 10 |

Pilkington S, Carli F, Dakin MJ, et al.

Increase in Mallampati

score during pregnancy.

Br J Anaesth. 1995;74(6):638-

642.

|

| 11 |

Boutonnet M, Faitot V, Katz A, Salomon L, Keita H.

Mallampati class changes during pregnancy, labour, and

after delivery: can these be predicted?

Br J Anaesth.

2010;104(1):67-70.

|

| 12 |

Ahuja P, Jain D, Bhardwaj N, Jain K, Gainder S, Kang M.

Airway changes following labor and delivery in

preeclamptic parturients: a prospective case control

study.

Int J Obstet Anesth. 2018;33:17-22.

|

| 13 |

Guru R, Carere MD, Diwan S, Morau EL, Saunders J,

Shorten GD.

Effect of epidural analgesia on change in Mallampati class during labour.

Anaesthesia. 2013;68(7):765-

769.

|

| 14 |

Hu J, Huang S, Tian F, Sun S, Li N, Xie Y.

A comparison

of upper airway parameters in postpartum patients: vaginal

delivery vs. caesarean section.

Int J Clin Exp Med.

2014;7(12):5491-5497.

|

| 15 |

Kodali BS, Chandrasekhar S, Bulich LN, Topulos GP, Datta S.

Airway changes during labor and delivery.

Anesthesiology.

2008;108(3):357-362.

|

| 16 |

Hui CM, Tsui BC.

Sublingual ultrasound as an assessment method for predicting difficult intubation: a pilot study.

Anaesthesia. 2014;69(4):314-319.

|

| 17 |

Jouppila R, Jouppila P, Hollmén A.

Laryngeal oedema

as an obstetric anaesthesia complication: case reports.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1980;24(2):97-98.

|

| 18 |

Hauch MA, Gaiser RR, Hartwell BL, Datta S.

Maternal and

fetal colloid osmotic pressure following fluid expansion

during cesarean section.

Crit Care Med. 1995;23(3):510-

514.

|