To the Editor,

Chest tube placement is a common procedure after thoracic surgery performed to drain fluid, blood, or air from the pleural cavity. We experienced a case of bilateral tension pneumothorax after video-assisted thoracoscopic esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction even after bilateral chest tube placement.

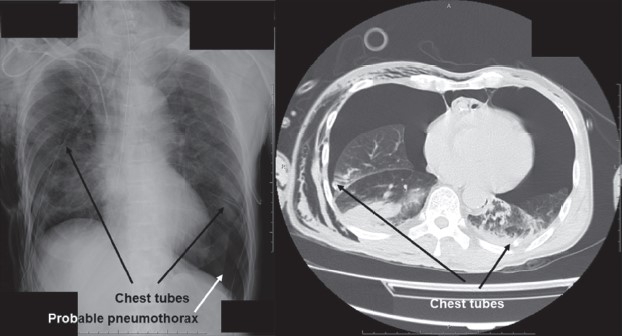

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A 67-year-old male with 5 L/min of oxygen administration through an oxygen mask was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) after the abovementioned procedures. During surgery, the right chest tube was inserted at the 8–9th intercostal space and the left chest tube at the 9–10th intercostal space at the level of the midaxillary line. Tracheal extubation was done before ICU admission. After admission, his percutaneous arterial blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) gradually decreased to around 90%, and he started agonizing terribly. At that time, both 3-chamber drainage systems did not show air leakage. Transthoracic echocardiography was immediately performed, which gave us a very poor view probably because of subcutaneous emphysema. Chest X-ray examination on the supine position was performed; however, although it was confirmed that both chest tubes were properly placed and probable pneumothorax was seen in the left lower lung field, massive pneumothorax was not definitely diagnosed (Figure 1, the left picture). Meanwhile, tracheal intubation and lung ventilation were performed because his respiratory and hemodynamic conditions deteriorated. His SpO2 was still around 90% even under manual ventilation with 100% oxygen with systolic blood pressure < 80 mmHg and heart rate > 120 bpm. A subsequent chest computed tomography (CT) was performed to determine the placement for additional chest tubes and revealed bilateral tension pneumothorax (Figure 1, the right picture). Immediately after CT examination, bilateral chest tube placement was performed at the 6–7th intercostal space at the level of the midclavicular line. After placement of new chest tubes, his respiratory and hemodynamic status stabilized. Consequently, tracheal extubation was done the next morning. His clinical course after extubation was uneventful.

Download full-size image

The black arrows indicate that both chest tubes migrated into the interlobar space. The white arrow indicates the probable pneumothorax in the left lower lung field.

This lethal event was probably caused by malfunctioning of the preplaced bilateral chest tubes. It should have been observed that no air leakage was a sign that the chest tubes were not draining. Malfunctioning of the chest tubes caused by chest tube malposition has been reported.1,2 However, there was no room for doubt that the preplaced bilateral chest tubes had been properly placed because they were placed under direct vision during surgery. Besides, it was suggested that it is sometimes difficult to assess chest tube positioning by a simple chest X-ray and a CT scan is often necessary to properly assess malpositioned tubes.3 Both chest tubes were placed in the interlobar fissure (Figure 1, the right picture). It was suggested that the high incidence of tube malfunction might be related to major fi ssure placement.4 The reason why these directly placed chest tubes migrated into the interlobar space is still unknown because accidental chest tube dislodgement is generally recognized as one of the delayed (but not early) complications of chest tube placement.1 The rate of interlobar malposition was significantly higher for lateral access rather than ventral access.5 Therefore, although they were certainly placed under direct vision, the preplaced chest tubes might have been placed as if using blunt dissection or trocar technique.5 Again, we should have noticed earlier that at least the left chest cube had not worked properly because probable pneumothorax was seen and the drainage system did not show air leakage, which might have meant the possibility of interlobar migration of the chest tube. In addition, it was a very rare and unfortunate event that both bilateral chest tubes did not work simultaneously, resulting in lethal bilateral tension pneumothorax.

The previous meta-analysis indicated that bedside ultrasonography had higher sensitivity and similar specifi city compared with chest X-ray examination in the diagnosis of pneumothorax.6 Therefore, transthoracic echocardiography was one of the promising options for detecting pneumothorax. However, the same review article also suggested that ultrasonography may not be appropriate for patients with subcutaneous emphysema, adhesion of pleura, thoracic dressings, pleural calcifications, or skin injury.6 As mentioned before, in this case, subcutaneous emphysema prevented us from obtaining fine ultrasound images.

Lastly, it has been emphasized that emergent needle decompression for tension pneumothorax must be performed in any patient who presents with hemodynamic instability or hypoxia before image confirmation.7 However, a high failure rate of needle thoracocentesis was also reported.8 It is undeniable that this negative information and overconfi dence in chest tube placement under direct vision ended up making us hesitate to perform emergent needle thoracocentesis.

In conclusion, regardless of what happens, we always need to keep in mind the possibility of chest tube malfunctioning even immediately after placement under direct vision.

References

| 1 |

Hooper C, Maskell N; BTS audit team.

British Thoracic

Society national pleural procedures audit 2010.

Thorax.

2011;66(7):636-637.

|

| 2 |

Havelock T, Teoh R, Laws D, Gleeson F; BTS Pleural

Disease Guideline Group.

Pleural procedures and thoracic

ultrasound: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease

Guideline 2010.

Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii61-ii76.

|

| 3 |

Baldt MM, Bankier AA, Germann PS, Pöschl GP,

Skrbensky GT, Herold CJ.

Complications after emergency

tube thoracostomy: assessment with CT.

Radiology.

1995;195(2):539-543.

|

| 4 |

Maurer JR, Friedman PJ, Wing VW.

Thoracostomy tube

in an interlobar fissure: radiologic recognition of a potential

problem.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139(6):1155-

1161.

|

| 5 |

Huber-Wagner S, Körner M, Ehrt A, et al.

Emergency

chest tube placement in trauma care—which approach

is preferable?

Resuscitation. 2007;72(2):226-233.

|

| 6 |

Ding W, Shen Y, Yang J, He X, Zhang M.

Diagnosis of

pneumothorax by radiography and ultrasonography: a meta-analysis.

Chest. 2011;140(4):859-866.

|

| 7 |

McPherson JJ, Feigin DS, Bellamy RF.

Prevalence of

tension pneumothorax in fatally wounded combat casualties.

J Trauma. 2006;60(3):573-578.

|

| 8 |

Kaserer A, Stein P, Simmen HP, Spahn DR, Neuhaus V.

Failure rate of prehospital chest decompression after severe

thoracic trauma.

Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(3):469-

474.

|