Abstract

Background

Several anesthetic techniques have been used for pilonidal sinus surgery such as general, spinal, and local anesthesia infiltration. However, the most effective technique remains controversial. The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of sacrococcygeal local anesthesia for complicated pilonidal cysts in terms of postoperative analgesic consumption.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted by collecting data from medical records for male patients who underwent pilonidal surgery using sacrococcygeal local anesthesia from 2008 to 2018. Patients’ demographics, operative data, and postoperative outcomes such as pain, nausea, as well as analgesic consumption at 0 and 3 hours were analyzed. Pain scores at rest and upon pressure were recorded using the Visual Analogue Scale. The length of complicated pilonidal sinus was considered to be greater than or equal to 7 cm with multiple openings.

Results

A total of 394 patients were included in the study, 173 patients (43.9%) had complicated cysts while 221 patients (56.1%) had uncomplicated cysts. The majority of patients were males (85.5% vs. 76.9% in the complicated and uncomplicated groups respectively). Patients’ weight was significantly higher in the complicated cyst group (87.12 ± 17.07 vs. 82.43 ± 20.30 kg,

Conclusions

Sacrococcygeal local anesthetic technique for complex pilonidal sinus surgery provided intra-operative hemodynamic stability as well as low post-operative pain and analgesic consumption.

Keywords

local anesthesia, pain, pilonidal sinus

Introduction

Pilonidal sinus disease is common in young adults.1,2 It is caused by the penetration of hair and cellular debris into the intergluteal cleft.1 Although the surgical corrective procedure is simple, it is associated with postoperative pain, wound infection, and discomfort especially if the defect was large and complicated.3-5

Several anesthetic techniques have been used for pilonidal sinus surgery such as general, spinal, and local anesthesia infiltration.3,4,6-8 However, the most effective technique remains controversial.5 In addition to the complications that could result from general anesthesia,9 patients might develop complications due to the prone position including cardiovascular and respiratory instability.10 Moreover, spinal anesthesia could be associated with complications such as hypotension and urinary retention, leading to delayed mobilization and discharge.6,11,12 In order to avoid these complications, sacrococcygeal local anesthesia has shown satisfactory outcomes since it resulted in decreased postoperative pain and hospital stay.7

Based on our previous publication,7 we conducted this study to assess the effectiveness of sacrococcygeal local anesthesia for complicated pilonidal cysts. The primary outcome measure was postoperative analgesic consumption.

Methods

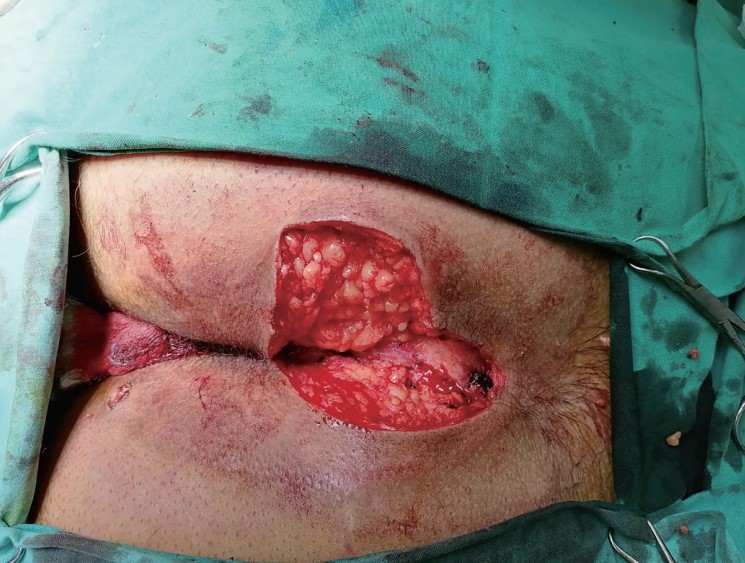

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted following the approval of the Institutional Review Board. A review of medical records from 2008 to 2018 of patients who underwent pilonidal surgery using sacrococcygeal local anesthesia from a single institution was performed. Inclusion criteria were patients whose age was 17 years and older. Patients’ demographics, operative data, and post-operative outcomes such as pain, nausea and vomiting, as well as analgesic consumption at 0 and 3 hours were analyzed. Pain scores at rest and upon pressure were recorded using the Visual Analogue Scale. Patients were divided into two groups, complicated versus uncomplicated pilonidal sinus. The length of complicated pilonidal sinus was considered to be greater than or equal to 7 cm with multiple openings (Figure 1). All patients were discharged on the same or the next postoperative day.

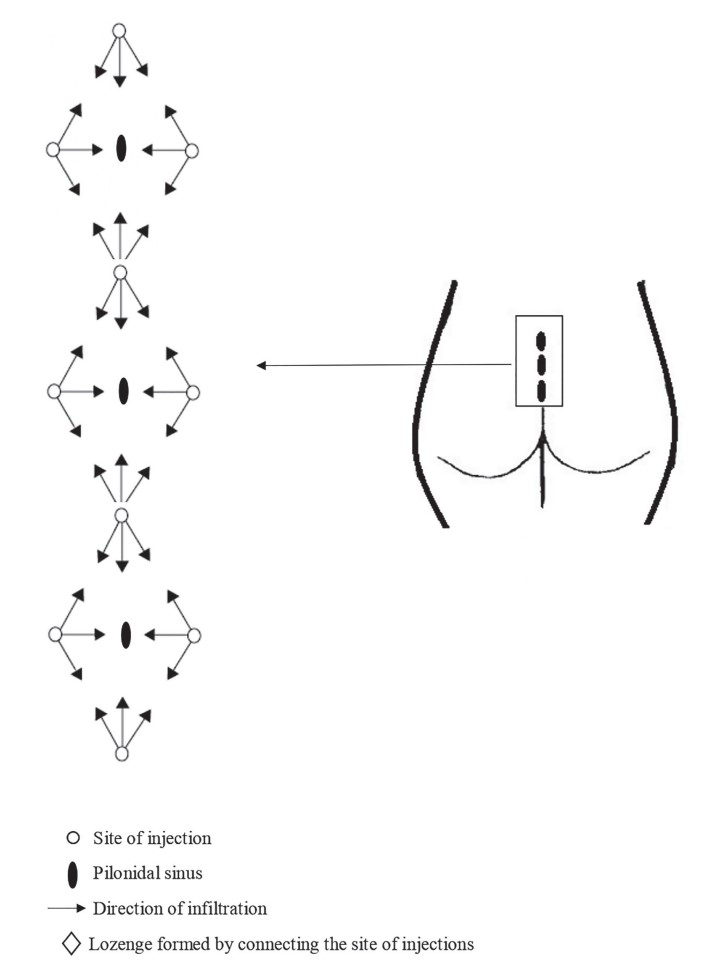

All patients received 1.5 µg/kg intravenous fentanyl preoperatively to tolerate the local anesthetic injections. The sacrococcygeal block was performed with the patient in the prone position. Four injection sites were marked: 4 cm above and below, and 3 cm lateral to the center of the pilonidal sinus on both sides. A “lozenge” shape is thus formed by connecting the injection sites. If the patient had a complicated pilonidal sinus, 2 or more “lozenge” were done as shown in Figure 2. Then the buttocks were pulled laterally with adhesive tape. After aseptic preparation of the skin, plain lidocaine 1% 0.3 mL was injected subcutaneously using an 8-mm 30 G needle (Micro-Fine Plus, Becton Dickinson, Dublin, Ireland) at each of the 4 injection sites. Each 20 mL of the local anesthetic mixture used for the block contained 10 mL lidocaine 2.0% and 10 mL bupivacaine 0.5%. A total of 40–60 mL of the local anesthetic mixture was used, depending on the patient’s weight.

Regarding the surgical technique, the cavity of the pilonidal sinus was marked by injecting 10 mL of methylene blue through one of the sinus openings. Elliptical incisions were made using cutting diathermy while preserving the presacral fascia. Then, excision of the pilonidal sinus was performed, followed by hemostasis. After that, depending on the degree of infection of the pilonidal sinus, either primary closure using interrupted 2⁄0 nylon sutures was done if there were signs of mild infection or the wound was left open and packed with antibiotic dressings if the pilonidal sinus was significantly infected (Sofratull, Roussel, England).7

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) program was used for data analysis. Bivariate analysis was conducted using the chi-square test for comparing categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s

Results

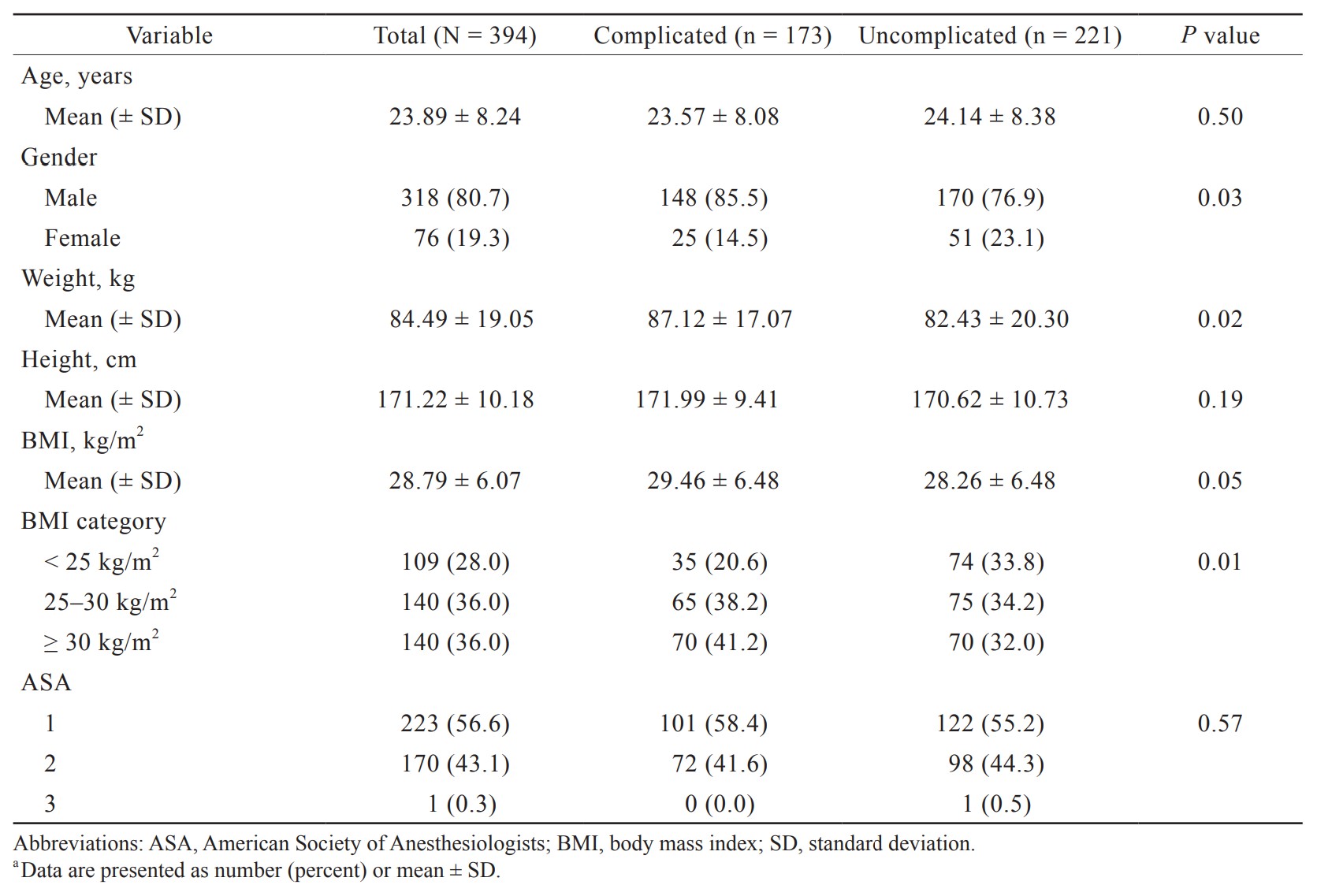

A total of 394 patients were included in the study, and 173 patients (43.9%) had complicated cysts while 221 patients (56.1%) had uncomplicated cysts. Patients’ age, height and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status were similar between the two groups. The majority of patients were males (85.5% vs. 76.9% in the complicated and uncomplicated groups respectively). Patients’ weight was significantly higher in the complicated cyst group (87.12 ± 17.07 vs. 82.43 ± 20.30 kg,

Download full-size image

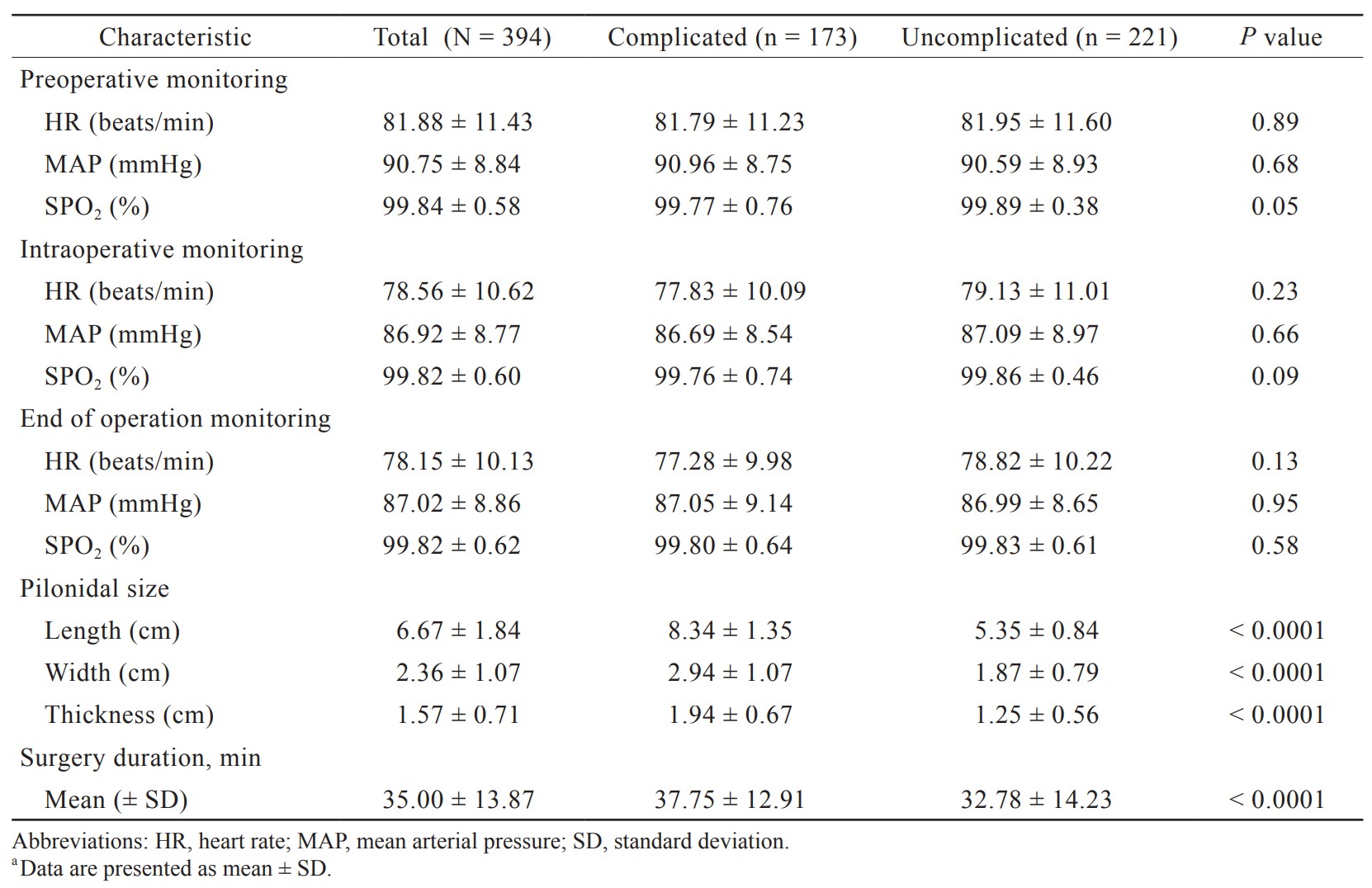

Mean arterial pressure and heart rate at baseline, intraoperatively and at the end of the operation were similar between the two groups (Table 2). The average pilonidal lengths for all patients was 6.67 ± 1.84 cm. Surgery duration was longer in the complicated group (37.75 ± 12.91 vs. 32.78 ± 14.23 min,

Download full-size image

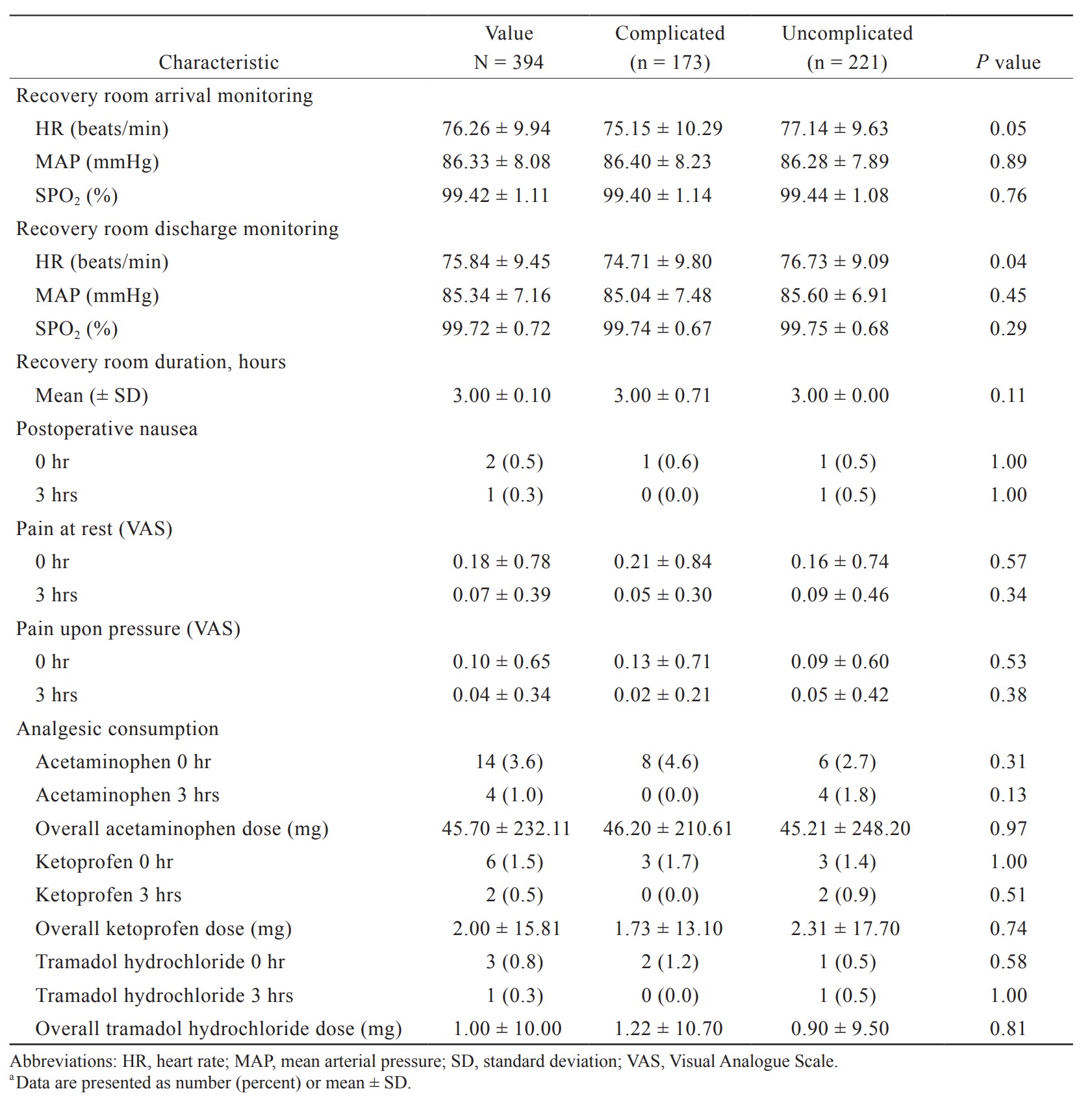

Recovery room hemodynamics were similar for the two groups. Two patients had postoperative nausea at 0 hour (1 patient in each group). Pain scores at rest and upon pressure were low in both groups. Analgesic consumption was similar between the two groups. Eight patients (4.6%) in the complicated group required acetaminophen (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roma, Italy) at 0 hour compared to 6 patients (2.7%) in the uncomplicated group. Three patients (1.7%) received ketoprofen (Sanofi Aventis, Paris, France) at 0 hour in the complicated group and 3 patients (1.4%) in the other group. Three patients, 2 (1.2%) in the complicated group and 1 (0.5%) in the second group required tramadol hydrochloride (Grunenthal GmbH, Aachen, Germany) (Table 3).

Download full-size image

Discussion

The major result of this study was that sacrococcygeal local anesthesia provided similar results for complicated versus uncomplicated pilonidal sinus surgery in terms of intra- and postoperative outcomes. Hence, sacrococcygeal local anesthesia could be used for complicated pilonidal sinus.

General, spinal, and local anesthesia are used for pilonidal sinus surgery.3,4,6 The use of local anesthesia infiltration has been increasing to eliminate the risk of complications associated with general and spinal anesthesia.8,13 Nevertheless, few studies used local anesthesia for complex pilonidal disease.8,13,14 De Nardi et al.14 performed surgery for complex pilonidal disease under local anesthetic infiltration. However, they used a large volume of local anesthesia (100–200 mL). In our study, 30–40 mL of local anesthetics were infiltrated. Burney3 provided local anesthesia for the majority of patients who underwent pilonidal surgery; however, they used spinal anesthesia in patients with complicated, extensive disease or large chronic abscesses. Eryilmaz et al.15 administered regional anesthesia for the surgical treatment of complicated pilonidal sinus. Similarly, another study16 used spinal anesthesia to carry out operations for complicated and recurrent pilonidal sinus.

In the present study, the prevalence of complicated pilonidal disease was 43.9%. The rate of complex sinus reported by other studies ranged between 17% and 66%.13,15,16 The mean weight of the patients was significantly higher in the complicated group compared to the uncomplicated group (87.12 ± 17.07 kg vs. 82.43 ± 20.30 kg,

In our study, the mean surgery duration in the complicated group was 37.8 ± 12.9 min. This was similar to the mean duration of procedure for complicated cysts under local infiltration reported by Porwal et al.2 (33 ± 11 min) and lower than that by Bertelsen13 (50 min). The mean defect size for complicated cysts in the present study was 8.3 ± 1.4 cm. This was similar to the size reported by Kokosis et al.1 Complicated pilonidal sinus in this study was defined to have a length greater or equal to 7 cm with multiple openings since this requires multiple lozenge to be made when anesthesiologists performed local anesthesia.

Regarding postoperative pain and analgesic consumption, in our study, the mean score in the complicated sinus group was 0.18 ± 0.78 at 0 hour and 0.05 ± 0.30 at 3 hours, with 4.6% of the patients receiving acetaminophen, 1.7% taking ketoprofen, and 1.2% requiring tramadol hydrochloride at 0 hour. In another study that used local anesthesia, around 50% of the patients had mild pain (numeric rating scale 1–3) during the first postoperative day and all patients required paracetamol and/or ibuprofen while none needed opiates.13 They used a tumescent solution containing mepivacaine (0.8 mg/mL), adrenaline (1 µg/mL), and sodium bicarbonate (42 µg/mL) in isotonic saline water to infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue around the natal cleft.13 The difference in pain scores and analgesic consumption between the two studies could be attributed to the different anesthetic infiltration technique used.

The local anesthesia infiltration in the current study did not include epinephrine unlike our previous study since epinephrine reduces intraoperative bleeding; however, this could mask postoperative bleeding which might occur.

Given the retrospective nature of the study, some limitations were that we were not able to assess wound healing, return to normal activity, and disease recurrence since patients were not followed-up. To use the sacrococcygeal local anesthesia technique for complex pilonidal disease in further clinical trials is needed.

Conclusions

The use of the sacrococcygeal local anesthetic technique for complex pilonidal sinus surgery provided intraoperative hemodynamic stability as well as low postoperative pain and analgesic consumption.

References

| 1 |

Kokosis G, Barbas A, Ong C, Levinson H, Erdmann D, Mantyh CR.

Flap repair of complex pilonidal sinus: a single institution experience.

Eur J Plast Surg. 2018;41(2):217-222.

|

| 2 |

Porwal A, Gandhi P, Kulkarni D.

Laser pilonidotomy—a new approach in management of complex pilonidal sinus disease: an exploratory study.

J Coloproctology. 2020;40(1):24-30.

|

| 3 |

Burney RE.

Treatment of pilonidal disease by minimal surgical excision under local anesthesia with healing by secondary intention: results in over 500 patients.

Surgery. 2018;164(6):1217-1222.

|

| 4 |

Rahmani N, Baradari AG, Heydari Yazdi SM, et al.

Pilonidal sinus operations performed under local anesthesia versus the general anesthesia: clinical trial study.

Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(9):200-206.

|

| 5 |

Luedi MM, Kauf P, Evers T, Sievert H, Doll D.

Impact of spinal versus general anesthesia on postoperative pain and long term recurrence after surgery for pilonidal disease.

J Clin Anesth. 2016;33:236-242.

|

| 6 |

Sungurtekin H, Sungurtekin U, Erdem E.

Local anesthesia and midazolam versus spinal anesthesia in ambulatory pilonidal surgery.

J Clin Anesth. 2003;15(3):201-205.

|

| 7 |

Naja MZ, Ziade MF, El Rajab M.

Sacrococcygeal local anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia for pilonidal sinus surgery: a prospective randomised trial.

Anaesthesia. 2003;58(10):1007-1012.

|

| 8 |

Garg P, Garg M, Gupta V, Mehta SK, Lakhtaria P.

Laying open (deroofing) and curettage under local anesthesia for pilonidal disease: an outpatient procedure.

World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(9):214-218.

|

| 9 |

Harris M, Chung F.

Complications of general anesthesia.

Clin Plast Surg. 2013;40(4):503-513.

|

| 10 |

Edgcombe H, Carter K, Yarrow S.

Anaesthesia in the prone position.

Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(2):165-183.

|

| 11 |

Liu H, Brown M, Sun L, et al.

Complications and liability related to regional and neuraxial anesthesia.

Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2019;33(4):487-497.

|

| 12 |

Rattenberry W, Hertling A, Erskine R.

Spinal anaesthesia for ambulatory surgery.

BJA Educ. 2019;19(10):321-328.

|

| 13 |

Bertelsen CA.

Cleft-lift operation for pilonidal sinuses under tumescent local anesthesia: a prospective cohort study of peri- and postoperative pain.

Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(7):895-900.

|

| 14 |

De Nardi P, Gazzetta PG, Fiorentini G, Guarneri G.

The cleft lift procedure for complex pilonidal disease.

Eur Surg. 2016;48(4):250-257.

|

| 15 |

Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Coskun A, Bas G, Sahin M.

Surgical treatment of complicated pilonidal sinus with a fasciocutaneous V-Y advancement flap.

Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(12):2036-2040.

|

| 16 |

Koca YS, Yıldız İ, Uğur M, Barut İ.

The V-Y flap technique in complicated and recurrent pilonidal sinus disease.

Ann Ital Chir. 2018;89(1):66-69.

|