Abstract

Background

Postoperative pain and postanesthesia shivering are the two common problems in patients undergoing surgery under spinal anesthesia (SA). The present study aimed to compare the preemptive prescription of the single dose of intravenous (IV) ketorolac versus nalbuphine on postoperative shivering and pain in patients undergoing surgery under SA.

Methods

Present study was a prospective, randomized double-blind study, conducted on patients of either gender, with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status class I or II, aged 21–60 years, posted for elective lower abdominal surgeries under SA. Patients were randomized by computer-generated random numbers into two groups of 50 patients each: group N (received 0.2 mg/kg nalbuphine IV) and group K (received 0.5 mg/kg ketorolac IV).

Results

The incidence of postoperative shivering was 22 % and 36 % in groups N and K respectively and the difference was statistically significant. The first request for analgesia (minutes) was later in group N (295.17 ± 54.62) than in group K (223.80 ± 15.34) and the difference was statistically significant. Increased total analgesic consumption was noted more in group K (131.34 ± 43.27) than in group N (79.23 ± 21.34), and the difference was statistically significant (

Conclusion

Preemptive nalbuphine had less incidence of postoperative shivering, delayed first request for analgesia, and less total analgesic consumption than ketorolac in patients undergoing surgery under SA.

Keywords

ketorolac, nalbuphine, postoperative analgesia, postoperative shivering, spinal anesthesia

Introduction

Postoperative shivering and pain are very common and unpleasant problems after surgery under spinal anesthesia (SA). If proper care is not taken, it can lead to increased morbidity, functional and quality of life impairment, delayed recovery time after surgery, prolonged use of analgesics, and higher health care cost.1 Preemptive analgesia is an intervention provided before the beginning of pain stimulation, which can reduce or prevent subsequent pain by blocking the transmission of noxious stimulation to the central nervous system.2

Median incidence of shivering related to SA was reported to be 55%.3 Vasodilatation, which promotes rapid heat loss and produces a transfer of body heat from the core to peripheral tissue, is the mechanism by which SA causes shivering.4 However, shivering is linked to a variety of negative effects such as increased metabolic heat and carbon dioxide production, increased oxygen consumption that can cause hypoxia and myocardial ischemia, increase pain from wounds, slow wound healing, and interference with monitoring of patients.5 Shivering may increase cardiac output, circulating catecholamines, intracranial and intraocular pressures, and blood pressure; it is considered a responsible factor for exacerbating postoperative pain and patient discomfort.6

There are numerous pharmacological and non-pharmacological preventive and therapeutic strategies available for the control of shivering. Nonpharmacological techniques include active cutaneous warming, radiant heat applied to the body’s surface, active forced air warming, electric heating pads, and radiant heating. Pharmacological interventions include drugs like pethidine, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, ondansetron, fentanyl, granisetron, and butorphanol, among others, have also been used for control of shivering in addition to nonpharmacological techniques.6,7 However, the role of preemptive drugs in the prevention of postoperative shivering is yet to be established.

Nalbuphine is a synthetic agonist-antagonist opioid that has characteristics of μ antagonist and κ agonist activities. Nalbuphine exerts its antishivering action through its high affinity for κ opioid receptors in the central nervous system.8 Nalbuphine is suitable for moderate to severe pain. It exerts sedative and analgesic effects by activating the κ receptor.9 Compared with other opioids, nalbuphine has a short action time and rapid clearance and is less likely to cause side effects such as nausea and vomiting, itching, urinary retention, respiratory depression, and excessive sedation.10

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) prevent postoperative shivering through the reduction of postoperative pain or inhibition of releasing vasoconstrictor and pyrogenic cytokines.11 Ketorolac has anti-inflammatory effects and it neither causes respiratory depression nor has other side effects like vomiting, itching, or hyperalgesic effects.12 The present study aimed to compare the preemptive prescription of the single dose of intravenous (IV) ketorolac versus nalbuphine on postoperative shivering and pain in patients undergoing surgery under SA.

Methods

The present study was a prospective, randomized, double-blind study, conducted over one and half years from August 2021 to December 2022 in the Department of Anesthesiology, after the study approval from Institutional Ethical Committee was gained (IEC/GMCK/91 dated 25th August, 2021).

Inclusion criteria

• Patients of either gender, with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Class I or II, aged 21–60 years, posted for elective lower abdominal surgeries under SA, who were willing to participate in the present study.

Exclusion criteria

• ASA status III or IV.

• Patient refusal.

• Severe cardiopulmonary disease.

• Pregnant patients.

• Patients with severe hepatic or renal disease.

• Patients with history of convulsions.

• Body temperature > 37.5°C.

• Hyper sensitivity to the drugs under study.

• Any contraindication to SA.

The study was explained to the patients in a local language and informed written consent was taken for participation in the study. Preanesthetic evaluation and basic laboratory investigations were done on all the patients, and they were explained in detail about the procedure of the SA during the preanesthetic visit. Patients were familiarized with the visual analog scale (VAS) (0—No pain, 10—–Worst pain) a day before surgery.

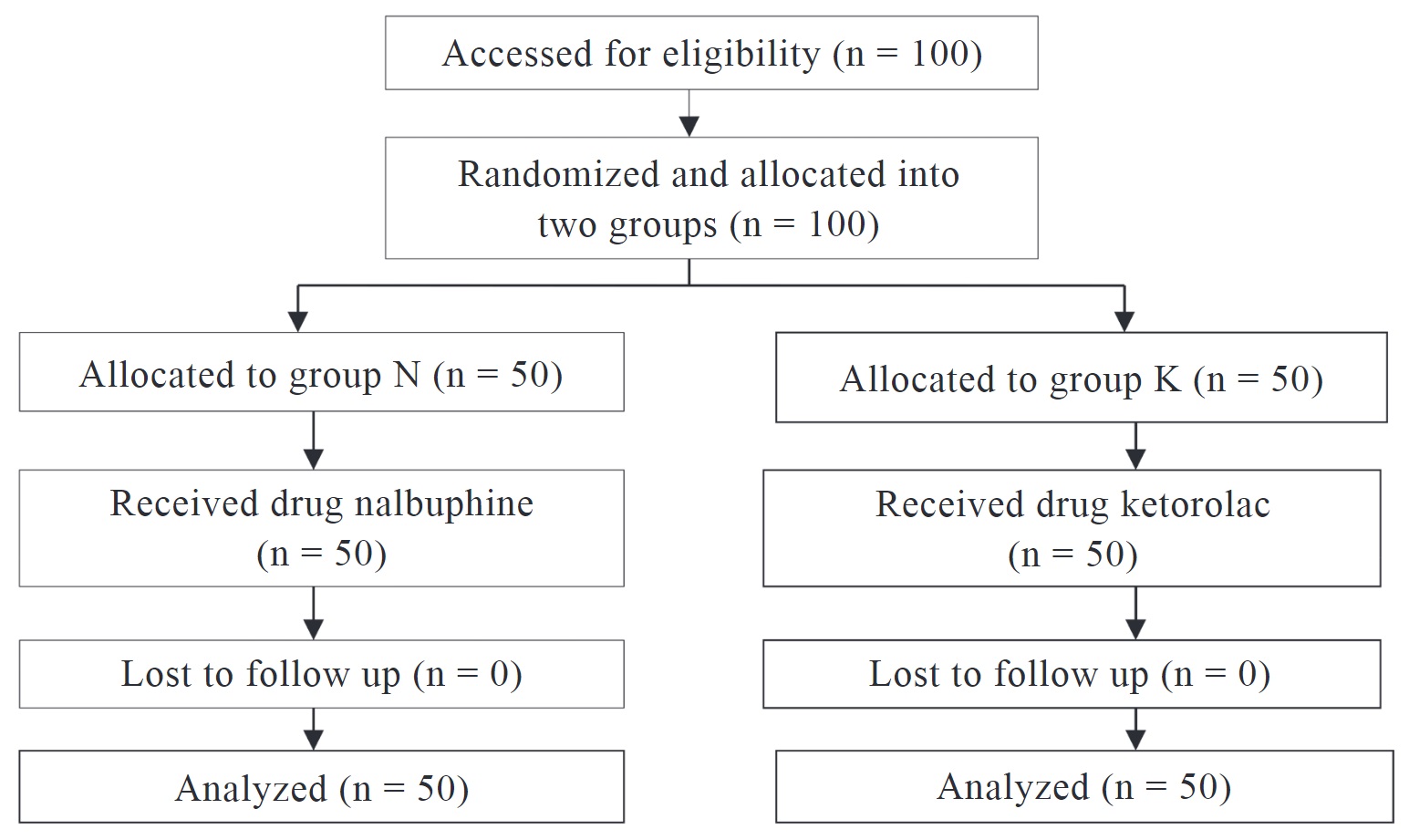

In the operating room, participants were randomly assigned to one of two study groups using sealed envelopes that were opened as soon as the patient entered. One hundred patients were randomized into two groups of 50 patients each (Figure 1):

• Group N: received injection of 0.2 mg/kg. Nalbuphine IV, 10 minutes before SA.

• Group K: received injection of 0.5 mg/kg. Ketorolac IV, 10 minutes before SA.

Download full-size image

Baseline mean arterial pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and partial pressure of oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded. In order to rule out confounding variables in this research, IV fluids and medications were kept at room temperature, and operation theatres were maintained at 22–24°C. IV access was secured with 18 G cannula. The study drug was administered to patients by an anesthesiologist who was unaware of the research hypothesis. Under all aseptic precautions, the part was cleaned and draped. Quinckes needle 26 G was inserted in L3–L4 space with patients in a sitting position and injection. Bupivacaine 0.5% heavy (3.5 mL) was given slowly after the free flow of cerebrospinal fluid was confirmed. Axillary temperature was recorded in both groups. The standard intraoperative and postoperative care were provided.

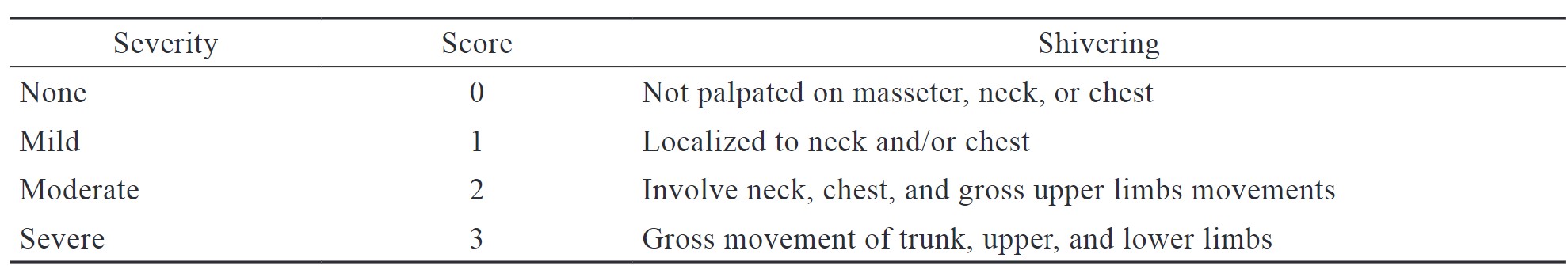

After the end of surgery, the primary outcomes such as incidence and severity of shivering and pain were evaluated. Shivering Assessment Score was used to assess shivering (Table 1).13 If shivering was noted, patients were treated with an anti-shivering injection of dose of tramadol (0.5 mg/kg IV).

Download full-size image

Postoperatively, pain score (VAS) was assessed at 1, 4, 8, and 12 hours. The duration of effective analgesia which was the time from the intrathecal injection to the first rescue analgesic requirement (VAS score > 3) was noted. Intramuscular diclofenac (75 mg) was administered as a rescue analgesic, and a total number of rescue analgesics required postoperatively in the first 12-hour period was recorded. Patients were also assessed for side effects such as nausea, vomiting, hypotension, pruritis, and bradycardia.

Data from previous studies was used to calculate the sample size.14,15 For a 90% chance of detecting a drop in the incidence of shivering from 50% to 25%, a sample size of 40 patients per group was needed, 50 patients were taken in each group so as to include the drop outs. Data was collected and compiled using Microsoft Excel, analyzed using SPSS 23.0 version (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency, percentage, means, and standard deviations were calculated for the continuous variables, while ratios and proportions were calculated for the categorical variables. Differences of proportions between qualitative variables were tested using a Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test as applicable. A

Results

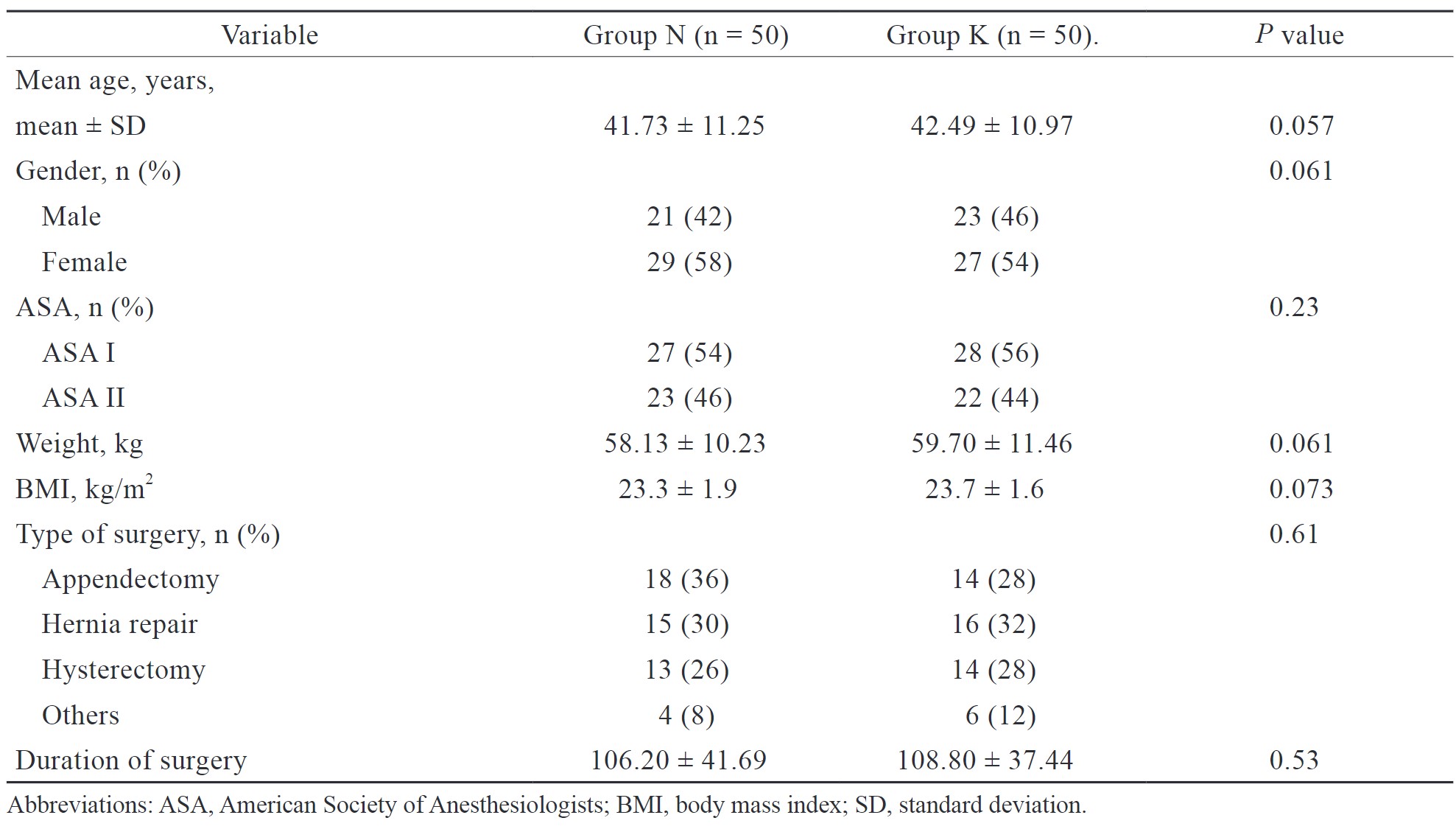

In the present study, 100 patients were randomly allocated into two groups, group N (n = 50) and group K (n = 50).Various parameters such as age (years), gender, ASA status, weight (kg), body mass index (kg/m2), type of surgery, and duration of surgery (min) were comparable among both groups and the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Download full-size image

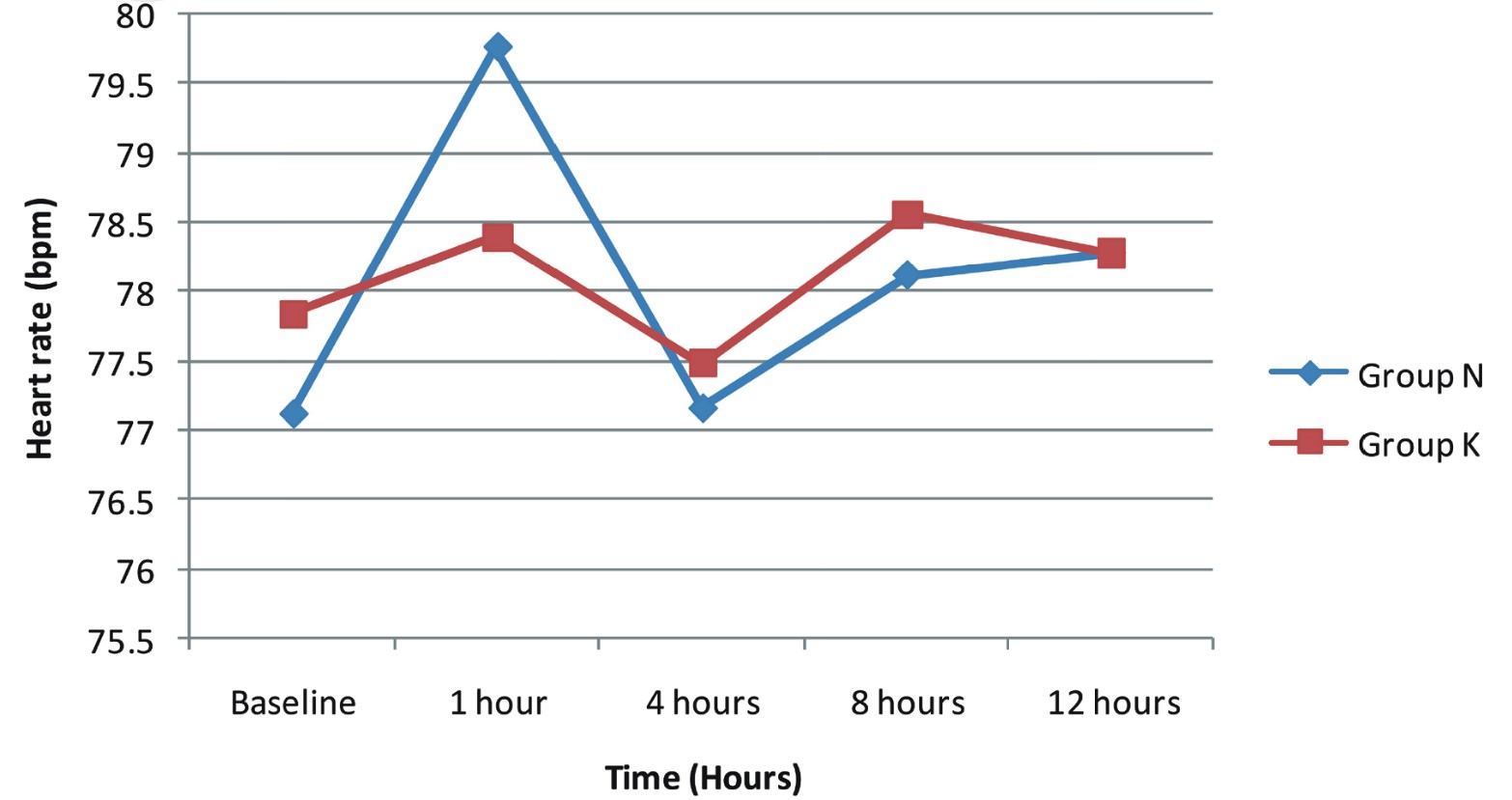

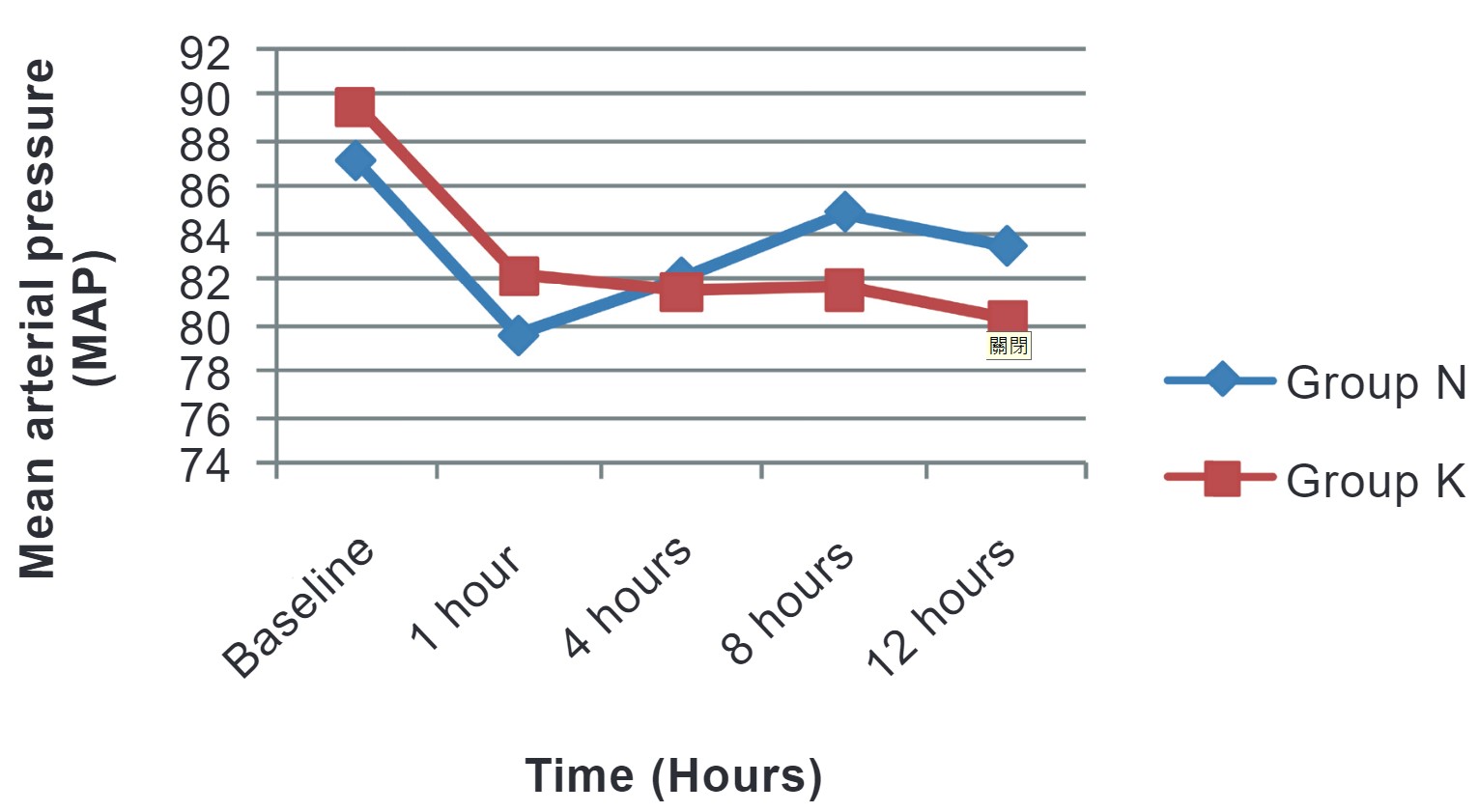

We compared hemodynamic variables in both groups at baseline, 1 hour, 4 hours, 8 hours, and 12 hours postoperatively. No hemodynamic instability was noted, and all variables were comparable among both groups and the difference was not statistically significant (Figures 2 and 3).

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

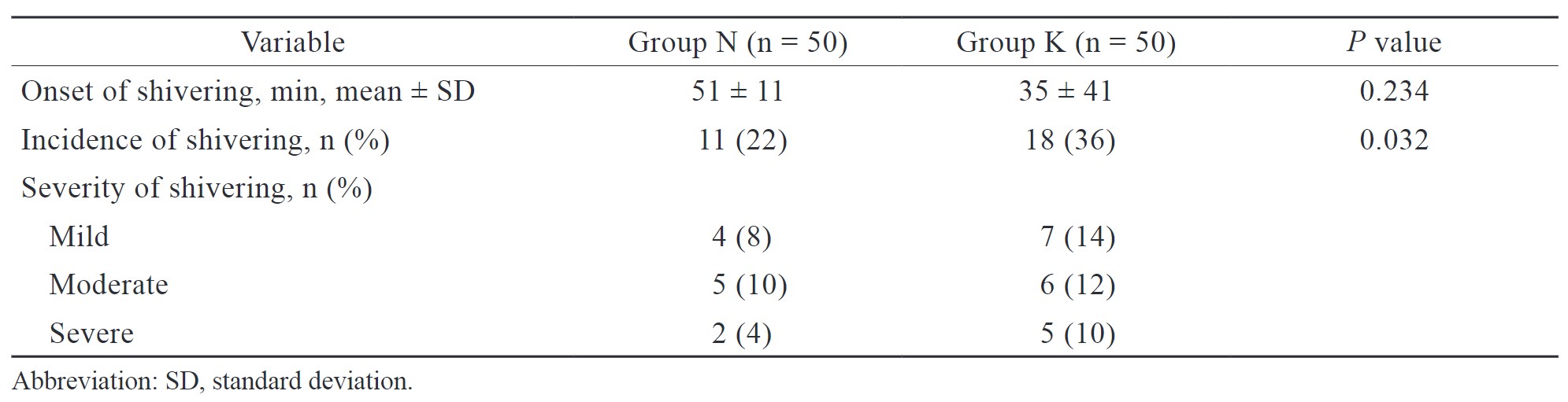

In the present study, the incidence of postoperative shivering was 22 % and 36 % in groups N and K, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (Table 3). The onset of shivering was earlier in group K (35 ± 41 min) than in group N (51 ± 11 min), but the difference was statistically insignificant (Table 3).

Download full-size image

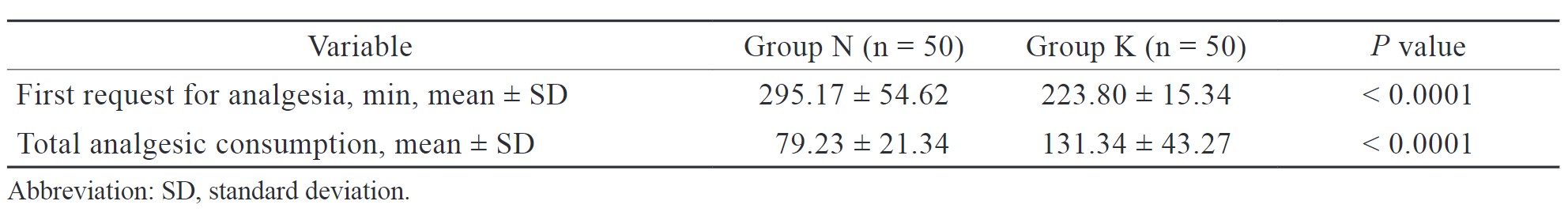

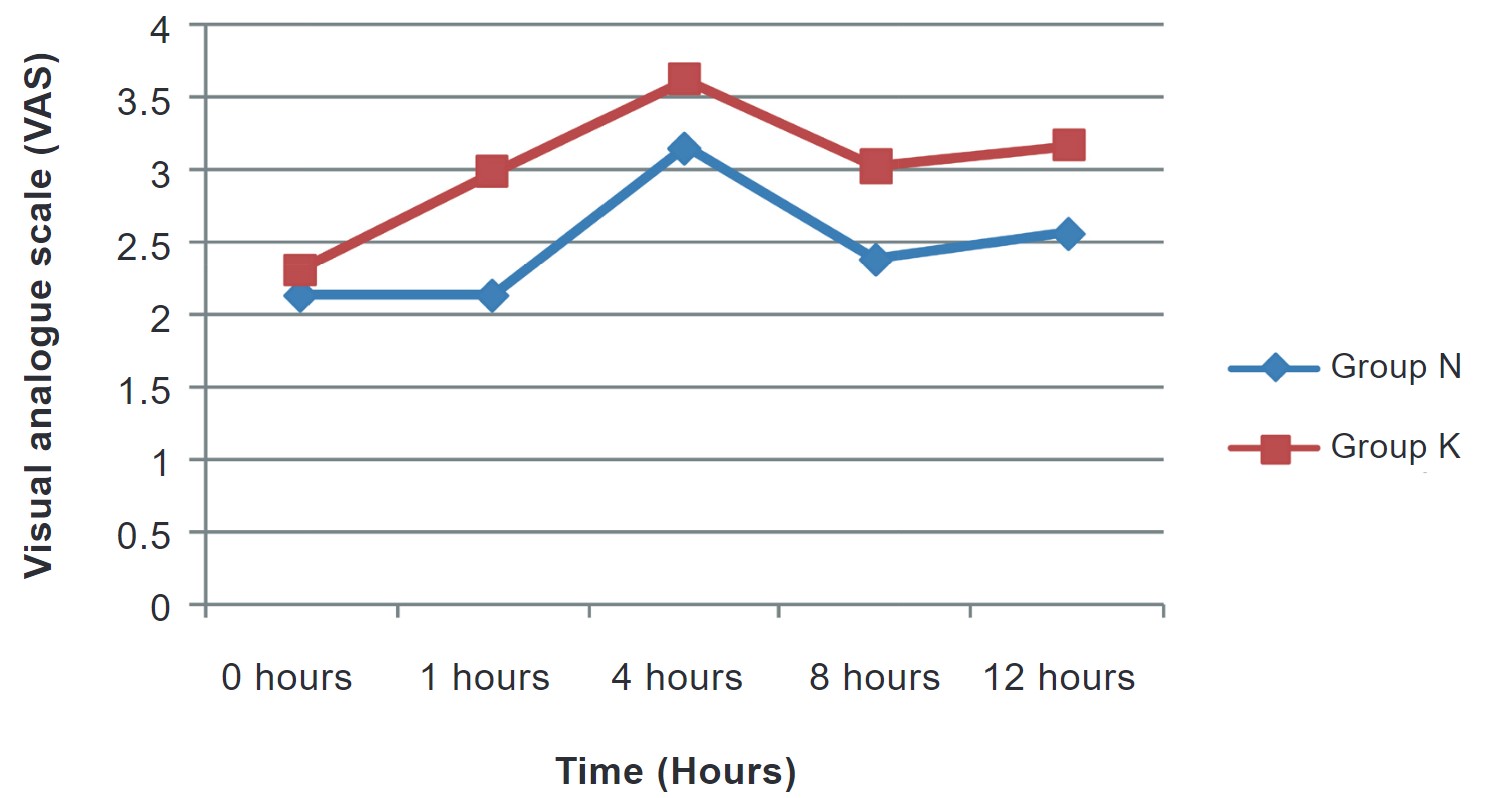

In our study, the request for first analgesia (min) was later in group N (295.17 ± 54.62) than in group K (223.80 ± 15.34) and the difference was statistically significant (Table 4). Increased total analgesic consumption was noted more in group K (131.34 ± 43.27) than in group N (79.23 ± 21.34), and the difference was statistically significant (Table 4). Postoperative analgesia was calculated on the basis of VAS scores. VAS scores in both groups were comparable at 1 hour but were not comparable at 4, 8, and, 12 hours in both groups, and the difference was statistically significant (Figure 4).

Download full-size image

Download full-size image

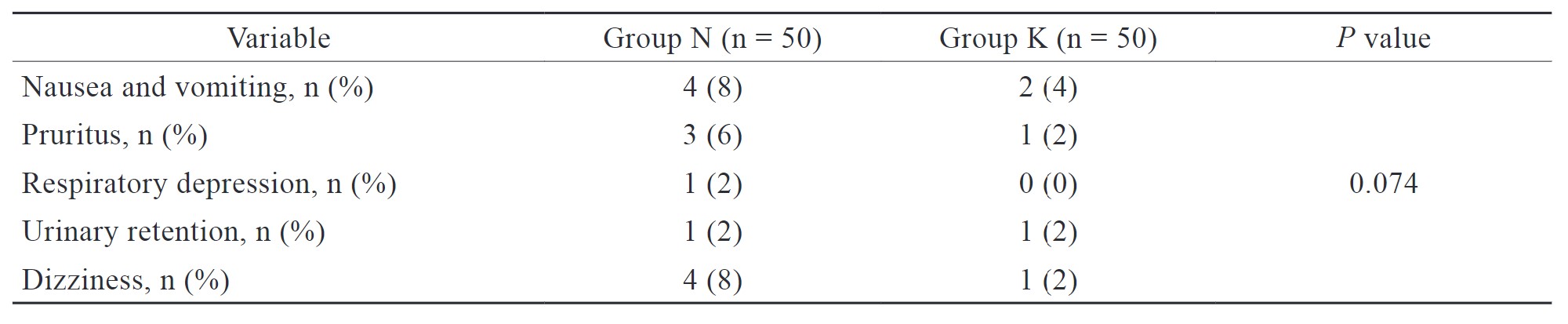

In the present study, the incidence of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness was slightly more in group N than in group K, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Download full-size image

Discussion

Pain and shivering are the two unpleasant problems in the postoperative period. Prophylaxis against shivering is very important to preventing its deleterious effects such as patients’ discomfort, increased O2 consumption, CO2 production, and lactic acidosis. Postoperative pain could be a provocative factor for postoperative shivering and shivering in turn aggravates postoperative pain by stretching of sutures. The present study evaluated the prophylactic role of nalbuphine and ketorolac for the prevention of postoperative shivering and pain.

Our findings are in contrast to the study conducted by Khezri et al.14 who compared the effect of a single preemptive dose of IV ketorolac (30 mg) with meperidine (50 mg) on postoperative shivering and pain in patients undergoing cesarean section under SA and concluded that ketorolac did not have significant difference with meperidine and can be considered for patients who have problems with the administration of opioids. In our study, we considered a single dose of preemptive IV nalbuphine a better choice as compared to ketorolac.

Eladi et al.15 studied the efficacy of a single dose of IV ketorolac (0.90 mg/kg) and nalbuphine (0.25 mg/kg) in relieving postoperative pain after tonsillectomy in children and concluded that IV ketorolac is more effective than IV nalbuphine in reducing pain intensity and postoperative analgesic requirement. This is in disagreement with our study which found nalbuphine more effective in reducing postoperative analgesic requirement which could be due to the fact that they used a higher dose of ketorolac than our study.

Kashif et al.16 compared the preemptive effects of IV paracetamol (1 gm) with ketorolac (30 mg) on postoperative pain and shivering after septoplasty under general anesthesia and concluded that paracetamol is better than ketorolac. They compared two NSAIDs but in our study, we compared NSAID with opioids and found that preemptive nalbuphine is superior to ketorolac for postoperative pain control and shivering.

In the present study, the incidence of shivering was reduced to 22 % and 36 % in groups N and K, respectively. The reduction in shivering was more in group N than group K which was statistically significant. Not only via IV route, there are many studies that have used nalbuphine prophylactically for the prevention of spinal-induced shivering via the intrathecal route. Mohamed et al.17, noted that shivering occurred in 20 patients (66.7%) in the control group, 7 patients in the nalbuphine group (23.3%), and 10 in the midazolam group (33.3%). They observed that even via the intrathecal route nalbuphine is more effective than intrathecal midazolam in the prevention of postspinal shivering for patients undergoing lower limb surgery.17

Nirala et al.18 concluded that IV nalbuphine and tramadol are effective for the control of shivering; however, the time taken for cessation of shivering is significantly less with nalbuphine when compared to tramadol. In our study, we also noted that the time taken for cessation of shivering was less in group N than group K,

Like our study, Karthik et al.19 observed that on comparing tramadol, ketorolac, and nalbuphine, nalbuphine produced effective analgesia with sedation and did not produce postoperative nausea and vomiting when compared to tramadol and ketorolac. Sun et al.20 conducted a study to compare the clinical efficacy and side effects of nalbuphine and dexmedetomidine for the treatment of shivering in women undergoing cesarean section under SA. They observed that nalbuphine considerably reduces shivering and eliminates adverse effects of shivering, which can enhance the postoperative experience for expectant patients.

NSAIDs reduce pain, inflammation, and fever, and improve postoperative ambulation following spinal surgeries.21 Exclusive use of NSAIDs for providing postoperative analgesia is, however, questionable. Nevertheless, ample support exists that their concomitant administration along with opioids provides better analgesia as compared to either of the two classes of drugs alone.22

The limitation of our study was the limited sample size; a single dose of study medication may not provide significant insights into the safety and efficacy of the medications. Postoperative follow-up of patients was kept for 12 hours for the study purposes. Larger studies are required to confirm our observations.

Conclusion

Preemptive nalbuphine had less incidence of postoperative shivering, delayed first request for analgesia, and less total analgesic consumption than ketorolac in patients undergoing surgery under SA. Further studies are needed for a better comprehension regarding the etiology and management of postspinal anesthesia shivering.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

| 1 |

Locketz GD, Brant JD, Adappa ND, et al.

Postoperative opioid use in sinonasal surgery.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(3):402-408.

|

| 2 |

Long JB, Bevil K, Giles DL.

Preemptive analgesia in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(2):198-218.

|

| 3 |

Crowley LJ, Buggy DJ.

Shivering and neuraxial anesthesia.

Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(3):241-252.

|

| 4 |

Amsalu H, Zemedkun A, Regasa T, Adamu Y.

Evidence-based guideline on prevention and management of shivering after spinal anesthesia in resource-limited settings: review article.

Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:6985-6998.

|

| 5 |

Zhang J, Zhang X, Wang H, Zhou H, Tian T, Wu A.

Dexmedetomidine as a neuraxial adjuvant for prevention of perioperative shivering: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

PloS One. 2017;12(8):e0183154.

|

| 6 |

Kranke P, Eberhart LH, Roewer N, Tramèr MR.

Pharmacological treatment of postoperative shivering: a quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Anesth Analg. 2002;94(2):453-460.

|

| 7 |

Onk D, Akarsu Ayazoğlu T, Kuyrukluyıldız U, et al.

Effects of fentanyl and morphine on shivering during spinal anesthesia in patients undergoing endovenous ablation of varicose veins.

Medi Sci Monit. 2016;22:469-473.

|

| 8 |

Eskandr AM, Ebeid AM.

Role of intrathecal nalbuphine on prevention of postspinal shivering after knee arthroscopy.

Egypt J Anaesth. 2016;32(3):371-374.

|

| 9 |

Mathai F, Portugal F, Mehta Z, Davis M.

Nalbuphine# 381.

J Palliat Med. 2019;22(11):1471-1472.

|

| 10 |

Zeng Z, Lu J, Shu C, et al.

A comparison of nalbuphine with morphine for analgesic effects and safety: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):10927.

|

| 11 |

Ebrahim AJ, Mozaffar R, Nadia BH, Ali J.

Early post-operative relief of pain and shivering using diclofenac suppository versus intravenous pethidine in spinal anesthesia.

J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30(2):243-247.

|

| 12 |

Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, Lanas A.

Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract.

Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(2):121-132.

|

| 13 |

Badjatia N, Strongilis E, Gordon E, et al.

Metabolic impact of shivering during therapeutic temperature modulation: the Bedside Shivering Assessment Scale.

Stroke. 2008;39(12):3242-3247.

|

| 14 |

Khezri MB, Mosallaei MAS, Ebtehaj M, Mohammadi N.

Comparision of preemptive effect of intravenous ketorolac versus meperidine on postoperative shivering and pain in patients undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study.

Caspian J Intern Med. 2018;9(2):151-157.

|

| 15 |

Eladi IA, Mourad KH, Youssef AN, Adbelrazek AA, Ramadan MA.

Efficacy and safety of intravenous ketorolac versus nalbuphine in relieving postoperative pain after tonsillectomy in children.

Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(7):1082-1086.

|

| 16 |

Kashif S, Kundi MN, Khan TA.

Pre-emptive effect of intravenous paracetamol versus intravenous ketorolac on post-operative pain and shivering after septoplasty under general anesthesia: a comparative study.

Pak Armed Force Med J. 2021;71(4):1179-1182.

|

| 17 |

Mohamed MAR, Ali HM, Badawy FA.

Nalbuphine vs midazolam for prevention of shivering in patients undergoing lower limb surgery under spinal anesthesia; prospective, randomized and double blinded controlled study.

Egypt J Hosp Med. 2021;82(4):761-766.

|

| 18 |

Nirala DK, Prakash J, Ram B, Kumar V, Bhattacharya PK, Priye S.

Randomized double-blinded comparative study of intravenous nalbuphine and tramadol for the treatment of postspinal anesthesia shivering.

Anesth Essays Res. 2020;14(3):510-514.

|

| 19 |

Karthik M, Selvakumar R, Vijayanand K.

A prospective randomized double blind study on postoperative pain relief in lower orthopedic surgeries—comparison between intravenous inj.

Indian J Anesth Analg. 2018;5(10):1654-1661.

|

| 20 |

Sun J, Zheng Z, Li YL, et al.

Nalbuphine versus dexmedetomidine for treatment of combined spinal-epidural post-anesthetic shivering in pregnant women undergoing cesarean section.

J Int Med Res. 2019;47(9):4442-4453.

|

| 21 |

Turner DM, Warson JS, Wirt TC, Scalley RD, Cochran RS, Miller KJ.

The use of ketorolac in lumbar spine surgery: a cost-benefit analysis.

J Spinal Disord. 1995;8(3):206-212.

|

| 22 |

Jirarattanaphochai K, Jung S.

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for postoperative pain management after lumbar spine surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9(1):22-31.

|