Abstract

Central venous catheterization (CVC) is a common invasive procedure. Although it is a relatively safe procedure, severe complications occurred sometimes. One of the most serious complications is large vessel perforation. A 40-year-old man was send to intensive care unit (ICU) after liver transplantation surgery with massive blood transfusion. Four days later, chest computed tomography (CT) were arranged for unknown leukocytosis and high level of procalcitonin. Chest CT revealed possibility of innominate vein perforation by CVC. Surgeon confi rmed the malposition of CVC complicated perforation and repaired innominate vein. Unfortunately, the patient passed away 8 days later after this re-operation even initially better condition after aggressive treatment. Delayed malposition of CVC is a rare cause for CVC complications. To minimize incidence of this severe complication, catheterization should be performed very carefully and post-procedure position checking is indicated.

Keywords

central venous catheterization; mediastinum; malposition;

Central venous catheterization (CVC) is a common invasive procedure for many clinicians because of hemodynamic monitor, drug or fluid administration, total parenteral nutrition supply or blood sampling. Although it is a relative safe procedure and most CVC related complications were mild, several severe complications such as infection, pneumothorax, hematoma and thrombosis were also reported.1 Among those severe complications, malposition induced hematoma of CVC is a rare but lethal one and it is always important to ensure the correct position for the catheter to reduce this complications. The incidence of catheter misplacement is approximately 5.01%.2 But most of them were benign and can be detected easily. Here, we reported a rare case with delayed malposition of central venous catheter and induced mediastinum hematoma due to innominate vein perforation.

A 40-year-old man is with alcoholic liver cirrhosis/ Child-Pugh C and complicated with hepatic function deterioration even after living donor liver transplantation, portocaval shunt creation and portal vein stent. He was admitted again and register on organ waiting list due to progressive liver failure. During administration, he was lucky to receive a cadaveric liver re-transplantation. In operation room, the anesthesia induction course was smooth and left neck CVC (12 French, Arrow International CR, Jamska, Czech Republic) was inserted because of the malfunction of his previous right neck CVC. Surgery was complete with huge blood loss (> 5,000 mL) (at least half of the blood infusion given via the left neck CVC) and the patient received twice re-laparotomy to control bleeding on the postoperative day 0 and day 2. On the midnight of postoperative day 2, the patient had a stable vital sign but febrile (39–40 °C) and also denied discomfort with unremarkable abdominal drain amount.

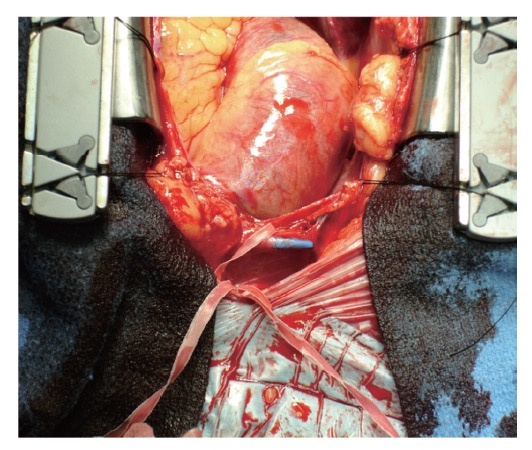

Unfortunately, on post-operative day 4, severe bandemia (> 44%) with high procalcitonin (> 161 ng/ mL) were noted, abdominal computed tomography (CT) (revealed normal) and chest CT was arranged for infection and graft evaluation. Chest CT presented moderate amount mediastinum hematoma. He underwent emergent sternotomy to repair innominate vein and surgeon confi rmed the malposition of CVC (Fig. 1 ). Unfortunately, the patient was in shock status after this re-operation due to cirrhosis induced coagulopathy and sepsis status. Hepatic failure was also on the next day and plasmapheresis was arranged to avoid possible acute rejection. The patient’s condition was improved 4 days later (postoperative day 8). But he was still in surgical intensive care unit (SICU) to treat mediastinitis. However, the patient still suffered from septic and passed away on postoperative day 16.

Download full-size image

There were some reports about the malposition of CVC. In addition, the symptoms of malposition were variant due to variant places which included severe chest pain, shoulder pain, arm pain or back pain.3 However, most of them can be found easily via X-ray checking or the malfunction of CVC when used for drugs or fl uid.3 But the delayed malposition of CVC were rare and hard to be proved. In our case, the procedure was performed smoothly and the waveform of CVC is normal during anesthesia course and the most important is that the drugs and blood were given without obstruction for packed red blood cells (pRBC) 28 U, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) 22 U, platelet 12U, cryoprecipitate 12 U and albumin 4 bottles during anesthesia. The hemodynamic status was volume responsive. Thus, we can be sure that the CVC is in the right place and the malposition of CVC happened after operation which present the unique of our case. However, we still did not know the precise time for the CVC tip penetration of the vessel.

Left-sided CVC and elderly patients were reported associated with higher incidence of complications.4 Longer left brachiocephalic vessel and a more oblique path to the heart maybe be the reasons and make that most malposition of CVC occurred on the left internal jugular vein. Due to the different distance between left and right internal jugular vein to right atrium, one study suggested that the right CVC should be 4 cm less than the left ones.5 One in vitro evaluation for venous perforation of CVC demonstrated that perforation is associated with CVC materials, number of lumens and angles of CVC to stimulated vessels.6 And the pressure waveform of CVC is also recommended more important than value in malposition of CVC.7 Those studies also hints that no single indictor is reliable to avoid the malposition. So we should alert and combined using imaging guidance (i.e. ultrasound), the feeling of resistance during CVC insertion, central venous pressure waveform checking to minimize this possible fatal risk.

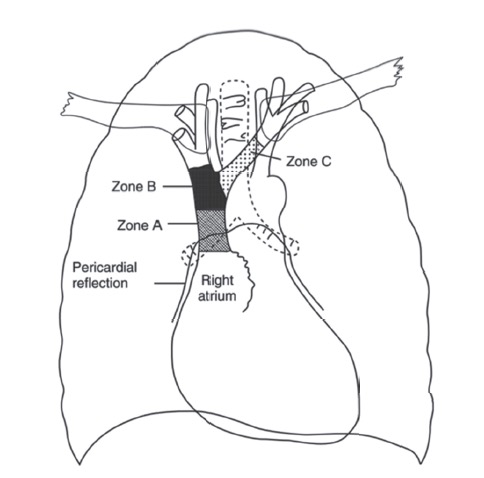

The carina is also though as a landmark for CVC tip position and suggested that left-sided catheters placement of the tip below the carina.8 Schummer et al. used stylized anatomy dividing the great veins and upper right atrium (RA) to three zones (zone A to C), representing different areas of significance for placement of CVCs.9 Zone A defi ned as from upper RA to lower lower superior vena cava (SVC); Zone B is from upper SVC to the junction of left and right innominate veins and Zone C is on the left innominate vein (Fig. 2 ). They further suggested that left-sided catheters require placement within zone A, for position at or below the carina; whereas right-side CVC should be put in zone B. The angle of the tip of the CVC to the spinous process can also predict if left side CVC is put above the carina.8 Electrocardiogram guidance of CVC placement can also be used. A fi rst signifi cant increase in P wave amplitude refl ected at pericardial area and maximal P wave amplitude can be founded when tip is at superior vena cava and right atrium junction.9 However, no any comparison study for these two methods was founded. For the management of CVC malposition, Siordia et al. suggest mini-sternotomy approach to provide suffi cient visualization of the vessel and surrounding structures with minimal complications and healing time.10

Download full-size image

We should consider the delayed possibility of innominate vein perforation by the tip of the central venous catheter after CVC procedure once unexplainable condition happened. To minimize this severe complication, we suggest using ultrasound-guided plus post-procedure radiography or electrocardiogram check to confirm the placement of the CVC tip and the depth of the left-sided CVC was recommended on 16 to 18 cm and in zone A.

Acknowledgements

All contributors for this study are those included in the authors.

Declarations

The authors claimed that there is no confl ict of interest for all parts of this manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

A copy of the written informed consent from NCKUHIRB is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Consent for Publication

A copy of the written informed consent from NCKUHIRB is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding of any kind for the preparation, submission of this manuscript.Authors’ Contributions

Yin-Ju Chen collected the data and wrote the manuscript. Yen-Chin Liu revised the manuscript. SCChung did conception and data interpretation. Shih-Chieh Chung was also involved in the anesthesia course of the case. All authors read and approved the fi nal manuscript.

References

| 1 |

Akıncı B, Duyu M, Alkılıç L, Yılmaz Karapınar D, Karapınar B.

Inferior petrosal sinus thrombosis in a child due to malposition of central venous catheter: a case report.

Med Princ Pract 2017;26:579–581.

|

| 2 |

Turi G, Tordiglione P, Araimo F.

Anterior mediastinal central line malposition.

Anesth Analg 2013;117:123–125.

|

| 3 |

Wang L, Liu ZS, Wang CA.

Malposition of central venous catheter: presentation and management.

Chin Med J 2016;129:227–234.

|

| 4 |

Walshe C, Phelan D, Bourke J, Buggy D.

Vascular erosion by central venous catheters used for total parenteral nutrition.

Intensive Care Med 2007;33:534–537.

|

| 5 |

Kim MC, Kim KS, Choi YK, et al.

An estimation of rightand left-sided central venous catheter insertion depth using measurement of surface landmarks along the course of central veins.

Anesth Analg 2011;112:1371–1374.

|

| 6 |

Gravenstein N, Blackshear RH.

In vitro evaluation of relative perforating potential of central venous catheters: comparison of materials, selected models, number of lumens, and angles of incidence to simulated membrane.

J Clin Monit 1991;7:1–6.

|

| 7 |

Lim JA, Jee CH, Kwak KH.

The malposition of a central venous catheter through a sheath introducer via the left internal jugular vein: a case report.

Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7187.

|

| 8 |

Stonelake PA, Bodenham AR.

The carina as a radiological landmark for central venous catheter tip position.

Br J Anaesth 2006;96:335–340.

|

| 9 |

Schummer W, Schummer C, Müller A, et al.

ECG-guided central venous catheter positioning: does it detect the pericardial reflection rather than the right atrium?

Eur J Anaesthesiol 2004;21:600–605.

|

| 10 |

Siordia JA, Ayers GR, Garlish A, Subramanian S.

Innominate vein repair after iatrogenic perforation with central venous catheter via mini-sternotomy—case report.

Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;11:98–100.

|