Historians sometimes cite the development of gunpowder as a great irony. While the chemical explosive and its modern progeny that power guns and bombs is associated with untold attenuation of human life, the ancient Chinese alchemists who invented it did so accidentally in pursuit of creating an elixir of immortality.1

The 19th Century Opium Wars

Another such irony of history, or rather a cascade of them, may be discerned in events and dynamics surrounding the Opium Wars of the mid-1800s and their sociopolitical consequences. Those wars between China and the British Empire arose over British smuggling of opium into China and British threats to the political status of the Chinese emperor. The British needed the profits from the illegal drug trade to pay for its own drug of choice of the day: China’s tea (or at least so felt many, for British society and leaders were sharply divided over the morality of its provocations, executions and resolutions of the confl icts). While the opium then smoked was nowhere near as potent as today’s formulations, its increasing use began to devastate the lives of individuals and families in China, especially in coastal cities, while its costs threatened the Chinese economy, then the world’s largest.2,3

The New Opium War

Numerous historical echoes or iterations of the Opium Wars can be seen as recapitulations of or variants on their major themes. For example, a complex set of events that occurred in Laos surrounding an opium trade and involving parties to the Laotian Civil War, the Shan of Burma, the Republic of China government then on Taiwan, marooned remnants of Chinese Nationalist forces, France, Thailand, and the United States, is known as the 1967 Opium War.4,5 An article published in a US magazine in 1971 referred to that situation as The New Opium War.6

The War on Drugs, the War on Pain, the Opioid Crisis

Even prior to this 50-year-old “new” opium war, there was occasioned a Western/US/global “war on drugs” whose instantiation is often associated with the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.7 The war on drugs has been widely deemed lost or failed by legions of experts and analysts,8-10 and convincingly so by The BMJ in a well researched 2016 editorial.11

The war on drugs has, beginning in the late 1990s and continuing today, evolved into, or expanded to encompass, the opioid crisis, also called the opioid epidemic: prototypically seen as a rapid exacerbation of mortality and medical, psychiatric, and social morbidity directly due to increased use of opioids, especially in the US or in the US and Canada.12

While policymakers and experts take various perspectives on the assessment of causes and prescriptions for clinical and social responses, the concept of balance is often applied to analyses of how the current crisis developed, and what to do about it. The overuse problems (e.g., still-increasing US overdose deaths) are seen by some as consequent to an overcorrection of earlier excessive and irrational fears of opioid use causing addiction (opiophobia). The pre-1990s (or so) perceived over-restriction was cast as a cause of a tragically unnecessary “pain epidemic,” especially problematic in East Asia, where it was felt that authorities were over-defensive against opioids due to the devastation suffered at the hands of Western imperialists over a century prior.13 However, it was also felt that North American clinicians and policymakers were severely undertreating pain due to Western cultural infl uences, such as Puritanism.14

A short letter by two US researcher-clinicians was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1980 in which they concluded that addiction in hospitalized patients receiving opioids was rare.15 An infl uential article propounded that pain was widely undertreated, often simply because clinicians were not asking about it and patients did not expect help with it, and that it should be considered the fi fth vital sign.16 Aggressive pharmaceutical marketing campaigns, now famously including that for OxyContin, followed.17 An ethos thereby coalesced within the public health and clinical communities that opioids could and should be widely prescribed, that freedom from pain was a human right which clinicians and policymakers were morally obligated to provide.

The New, New Opium War

Now the pendulum in the US has swung into the panic zone in the other direction, and with understandable impetus. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “In 2015, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths in the United States was more than 2.5 times the rate in 1999.” 18

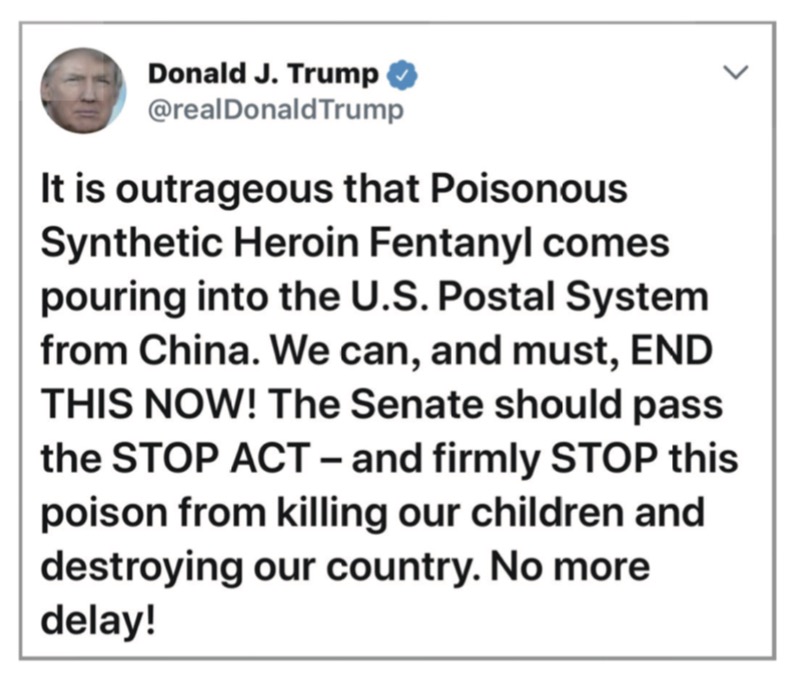

As researchers and clinicians attempt to evaluate and re-evaluate this complex, multifactorial problem, US President Donald Trump pointed his fi nger at China, tweeting on August 21st a statement baldly accusing “China” of sending “poison” into the country, “killing our children” (Fig. 1).19 Trump also pointed a fi nger at Mexico and China for exporting opioids into the US, characterizing it as “almost a form of warfare.” 20

The first war Trump waged against China, during his campaign before he was elected, was one of rhetoric. Once in offi ce, he proclaimed a trade war. With these recent statements, it appears that the main commodity Trump offers for export to China is blame and vitriol. To whatever measure Trump’s scheme works, it will cost the US, in continued misery. You cannot solve a problem by pretending it is someone else’s.

Download full-size image

Acknowledgements

James L Reynolds, globalization editor at The Asian Journal of Anesthesiology provided writing assistance.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

References

| 1 |

Ling W.

On the invention and use of gunpowder and firearms in China.

Isis 1947;37(3/4):160–178.

|

| 2 |

Fairbank JK, Goldman M.

China: A New History.

2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 2006.

|

| 3 |

Dormandy T.

Opium: Reality’s Dark Dream.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2012.

|

| 4 |

St. Clair J, Cockburn A.

The US opium wars: China, Burma and the CIA. CounterPunch.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/12/01/the-us-opium-wars-china-burmaand-the-cia/. Accessed November 1, 2018.

|

| 5 |

McCoy AW.

The politics of heroin: CIA complicity in the global drug trade.

Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, Chicago Review Press; 2003.

|

| 6 |

Browning F, Garrett B.

The new opium war.

Ramparts Magazine. May, 1971. http://www.unz.com/print/Ramparts-1971may-00032/. Accessed October 27, 2018.

|

| 7 |

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Single convention on narcotic drugs, 1961.

https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/single-convention.html. Archived: http://www.webcitation.org/73WqN9xmJ

|

| 8 |

Bould MD, Enright A.

The “war on drugs” you did not hear about: the global crisis of access to essential anesthesia medications.

Can J Anaesth 2017;64:242–244.

|

| 9 |

Hughes B, Matias J, Griffiths P.

Inconsistencies in the assumptions linking punitive sanctions and use of cannabis and new psychoactive substances in Europe.

Addiction 2018.

|

| 10 |

Global Commission on Drug Policy.

Regulation: the responsible control of drugs.

http://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/reports/regulation-the-responsible-control-of-drugs/. Archived: http://www.webcitation.org/73W4GeXnh

|

| 11 |

Godlee F, Hurley R.

The war on drugs has failed: doctors should lead calls for drug policy reform.

BMJ 2016;355:i6067.

|

| 12 |

National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Opioid overdose crisis.

https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis. Archived: http://www.webcitation.org/73WIwwqJd

|

| 13 |

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

World Drug Report 2018: 1-Executive Summary.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2018. Source URL: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/ Source archived: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/ PDF: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/prelaunch/WDR18_Booklet_1_EXSUM.pdf PDF archived: http://www.webcitation.org/73WY0VJZU

|

| 14 |

Sun WZ, Hsieh YJ, Lin CS, et al; Taiwan Pain Forum.

The law of Yin and Yang for controlled drugs ecosystem: maximal analgesia with minimal abuse.

Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 2015;53:117–118.

|

| 15 |

Porter J, Jick H.

Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics.

N Engl J Med 1980;302:123.

|

| 16 |

Max MB, Donovan M, Miaskowski CA, et al.

Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain.

JAMA 1995;274:1874–1880.

|

| 17 |

Van Zee A.

The promotion and marketing of oxycontin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy.

Am J Public Health 2009;99:221–227.

|

| 18 |

Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM.

Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2015.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db273.htm. Archived: http://www.webcitation.org/73ZWuUfXm

|

| 19 |

Trump DJ.

“It is outrageous that Poisonous Synthetic Heroin Fentanyl comes pouring into the U.. Postal System from China. We can, and must, END THIS NOW! The Senate should pass the STOP ACT—and firmly STOP this poison from killing our children and destroying our country. No more delay!”

Twitter. https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/1031590431379865600?lang=en.Updated August 20, 2018. Accessed October 31, 2018.

|

| 20 |

Benner K.

Snaring doctors and drug dealers, justice dept.

Intensifies opioid fight. The New York Times. August 22, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/22/us/politics/opioids-crackdown-sessions.html. Accessed: October 29, 2018

|